Place of Discourse and Folklore of the African Diaspora

On being white and talking about racism. How to learn about Afro-Brazilian stories of resistance, through lenses free from the objectifying effects of the white gaze.

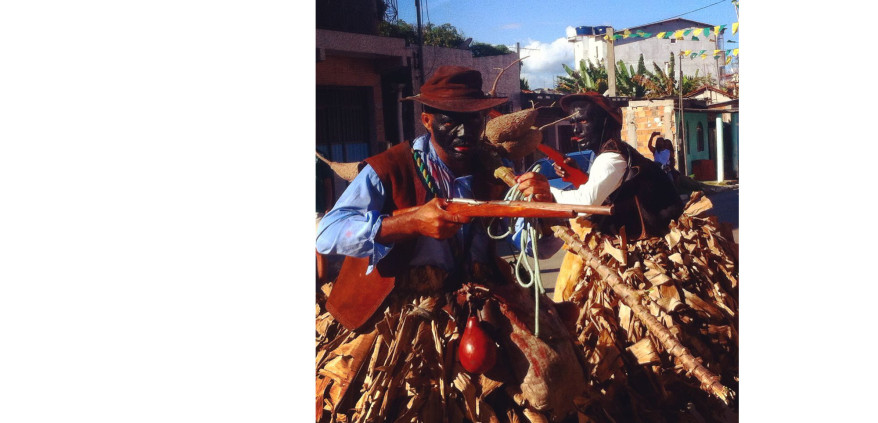

Each Sunday of July, a small Brazilian town called Acupe hosts street theater folklore of the African Diaspora. People come from all over the world to witness this unique cultural manifestation, and to support the community's effort to reclaim its history. Nego Fugido (the play's title, which I'll roughly translate as “runaway black guy") represents the long overdue opportunity for Afro-Brazilians to tell their own stories of resistance, spirituality, and ancestry. This way, they combat invisibility and the twisted white gaze of recorded history and western anthropology.

This play is about enslaved Africans who ran away, then were chased and killed by their master. This master was trying to avoid bankruptcy by offering the lives of enslaved runaways to Ikú (an Orixá, a force of nature, Death itself in the Afro-Brazilian religion Candomblé), and planting a banana tree over each grave. Eventually, there are no more lives to be offered, and Ikú curses the whole town. Every year, good spirits must be sent out to chase away the bad ones and break the curse. Caretas, the masked children that roam the streets, symbolize the “insertion of blacks and their culture into Brazilian society" (Jamilson Oliveira). Ultimately, the enslaved are granted freedom, and the town manages to arrest and auction out the King. Today, the skirt made out of dried banana tree leaves worn by the performers holds immense spiritual power, symbolizing the sacrificed lives of their ancestors.

“The banana tree leaves themselves are used in Candomblé terreiros to scare away eguns (spirits). Every terreiro has a babá of the house, a good egun that prevents other eguns from disrupting celebrations and rituals." (Jal Souza)

The story, which comes from oral tradition of a couple hundred years ago, is remembrance of colonial power dynamics, the brutality of the struggle for freedom, and the primordial strength of Ikú. Acupe is a Quilombola community at the “Bay of All Saints" (Bahia de Todos os Santos), a region with a long colonial history, and land with deep ancestral roots. The combination of lifelike reenactments, on the Land where the story took place hundreds of years ago, and the sacred ritual to rid the town of evil spirits makes for a breathtaking experience.

Unfortunately, the swarm of white photographers overpowers not only the audience, but also the performers. There is nothing inconspicuous or ordinary about those giant lenses being shoved at all angles and in all directions. These hybrids between tourists and professionals felt no shame in interrupting the performances to direct the actors into ideal poses. The drone hovering over us witnessed hostile arguments between photographers who fought over an ideal viewpoint, or between audience members that just couldn't take those people's entitlement over some cubic meters of aerial space.

Perhaps the the lack of a formal theater setting caused uncertainty over of what would constitute etiquette. Or perhaps they felt that this was a once in a life time opportunity to register that moment. What is certain is that the colonial gaze, and the historical form of racism being depicted in the play, was also manifested in its modern form, making people very anxious.

The population of Acupe is predominantly black. So, when there are white people there they are seen as outsiders. In fact, a lot of white people show up only to document this event, and the objectifying effects of the white gaze are palpable.

I believe there is a level of entitlement that comes through when white people act like being there and documenting the event is a favor they are doing for the community, as if their presence there is what gives the event value. There is absolutely no way that a photographer would interrupt an actor's performance with “psssst! pssst!" while aggressively pointing to where the actor should move for a better shot at Shakespeare at the Park in NYC.

The “epidermalization of inferiority" may or may not come at play in response to this, but it is easy to imagine that many black people feel that the “social cost" of calling out white people's insensitive behavior is too high, aside from having to deal with a likely outburst of white fragility. What I can say is that a hand full of black people in the audience were pushed too far and lashed out at arrogant gazers who were clueless and disrespectful.

I was taking pictures with my phone... the costumes were beautiful and designed to be photogenic. The problem isn't visiting the town for the event, watching the performance and taking pictures. The problem is treating the Other as there to serve You.

One extremely insensitive thing you can do as an audience member is to treat those performers as objects, as if their purpose for being there was for you to make a fantastic photo. The parallels between history and modernity are distressing. The community is passing down a tradition to their children, honoring their ancestors on the very land where their blood seeped into the ground. Being able to witness it should be taken as a humbling learning experience.

Place of Discourse

As someone who is not black or of the African Diaspora, I tell this story partially. I don't, nor will I ever want to, speak for anyone. I speak about them, and about myself, because we exist in relation to each other, dialectically. My place of discourse is not, and doesn't claim to be, impartial. That doesn't mean I have no right to speak.

“[W]hite people cling to the notion of racial innocence, a form of weaponized denial that positions black people as the “havers” of race and the guardians of racial knowledge." (Robin DiAngelo)

It's my responsibility to address my white passing privilege, and to address how my own community might be reproducing classism and colorism. As white (passing) people, we must listen and learn (and read), but when we demand the unpaid emotional labor of racial education from Afro-descendants, we fall in the trap of reproducing the very thing we want to eradicate.

Support the community, don't take from them. Learn without demanding labor. And attend when you're invited. This is the etiquette we can establish.

Mirna Wabi-Sabi

is co-editor of Gods&Radicals, and writes about decoloniality and anti-capitalism.