Opening the Seals

“Death is not the enemy of life, but godlessness. The despair of humanity today is the product of centuries worth of both the denial of the spiritual life of the world and the suppression of the natural urge to reintegrate with that world."

For those to whom a stone reveals itself as sacred, its immediate reality is transmuted into supernatural reality. In other words, for those who have a religious experience all nature is capable of revealing itself as cosmic sacrality.—Mircea Eliade

We ought to dance with rapture that we should be alive and in the flesh, and part of the living, incarnate cosmos.—D.H. Lawrence

Death is not the enemy of life, but godlessness. And I do not speak of an impersonal and immaterial God, who dwells in the realm beyond the earth, demanding slavish obedience. Rather I speak of the living soul of the world, which has many names and it’s law is written into the mountains and rivers. There can be little doubt now that the end has come. And though we cannot hope to avert what is coming, we may still take stock of ourselves in the darkening twilight and reconsecrate bonds long forgotten. Since the beginning, humanity has misunderstood the doom which it has wrought upon the world. As we shall see in what follows, however, I believe there were moments during the birth of industrialization when brave souls perceived the vastness of what had occurred.

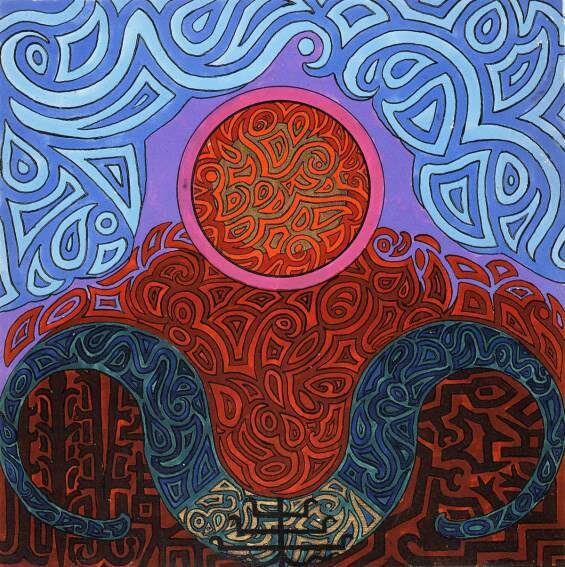

Our dialogue surrounding the end of the world is part of the problem. This is particularly true for those who have not yet accepted its inevitability. What is the nature of our crime? The extinction of countless species, the collapse of the world’s oceans, the eradication of the world’s forests. Do we weep for them? Or do we weep for ourselves because we know we cannot live without them? As it turns out, both are misguided. The world will rebuild itself in time and our civilization is not worth saving. Whether or not our species is will be determined by forces far greater than ourselves. But if, as Robinson Jeffers wrought, the death of millions of humans is no more than the death of so many flies, then what does that say about the value of the fly? The flaming heart of the universe is indifferent to the deaths of countless billions, whether they are humans, bears, whales, bees, or daffodils. What matters is that every breath and every drop of blood sings in reverence to this spirit of the world, pulses with the energy and vitality of the gods. And in this regard, is humanity chiefly lacking.

Do we imagine that something is irrevocably lost when a species is extinguished? The cosmos is a spiral and what has come will come again. The earth does not need our tears. This should be clear to all who do not imagine that humanity is the architect of the universe. Likewise, how many can truly weep at the fall of techno-industrial society? Did we ever imagine that the world could or should sustain so many billions of human? How else was this ever going to end? Wherein, in other words, does the sacredness of life reside? Death is not the enemy of life, but godlessness. We think too highly of our power when we talk of destroying the earth. The purpose of life is not that nothing should ever die. Species come and go. The universe will not weep for the salmon because we turned the oceans to barren acid anymore than it wept for the Irish Elk because its own glory condemned it to death. The world has been ruined and remade countless times. We imagine that we are special because we have caused the present crisis, which confirms our believe that humanity stands at the center of the universe. And we live in terror of our own destruction because we cannot stand the idea that the world will be fine and perhaps better without us. Thus either of the two dominant perspectives is inseparable from an anthropocentric orientation.

The sin of techno-industrial society is not that it kills and destroys. But that it denies the divinity of the world and within humanity. To take the life of an animal and honor the spirit within it is to assert the sacred world. To take the life of an animal and treat it as nothing more than so much biological material is to deny its meaning, which is far worse than taking its life. Thus what is needed at this moment of reckoning is a resacralization of the world. This is the closest we can get to atoning for what we have done, by addressing the precise nature of our crime. Not in killing, as humanity has done since it first appeared on the earth, in full reverence of the divine cosmos. But in denying the spirit of the world itself. In other words, the true horror of our age and the content of the crisis we now face is the triumph of a disembodied, dualistic conception of humanity and the earth. And it is likely that we will not survive the consequences of this division, the product of the logic of industrialism.

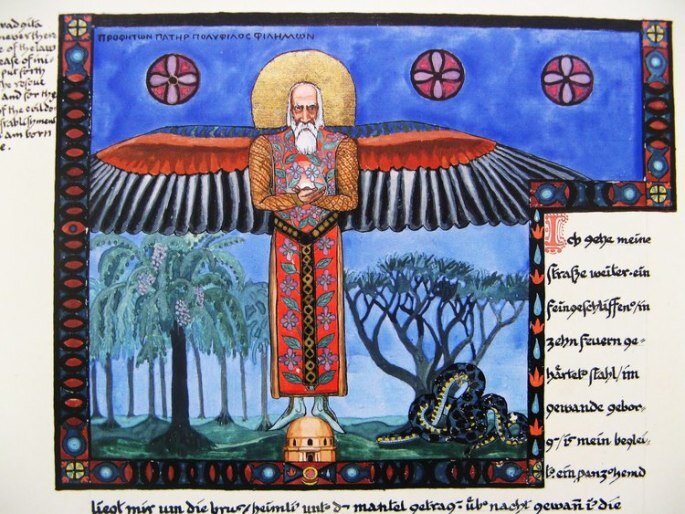

As we have said elsewhere, D.H. Lawrence had a particularly astute understanding of what had been lost through industrialization. Nowhere was this understanding better articulated than in his final work, which was completed only months before his death. Apocalypse, Lawrence’s reflections on the Book of Revelations, is a strange text by any estimation. It is part exegesis and part manifesto. In the first case, it may seem strange that Lawrence wrote a book about the bible at all. While he described himself as being “passionately religious,” his hostility towards Christianity was undisguised and vociferous. But despite having abandoned his Christian upbringing early in his life, The Book of Revelations nevertheless exerted a tremendous influence on his later work. For Lawrence, the significance of Revelations was as a sort of manual for humanity to rediscover the nature of the world that had been forgotten over long centuries of industrialism, both in terms of the alienation is caused within the human race and in terms of the vile destruction it had caused in the natural world. It was, for him, a path that lead to both the liberation of the self and restoration of nature.

As renowned Lawrence scholar Mara Kalnins writes, “revelation, he [Lawrence] argued, was a symbolic account of how to attain inner harmony as well as a sense of living connection with the greater universe.” Indeed, it is surprising that Lawrence is so rarely thought of as an ecological writer. As deep ecology pioneer Dolores LaChapelle and others have argued, however, Lawrence deserves to be counted, alongside Thoreau and Muir, as one of the preeminent environmental writers. Like Jung, Lawrence’s childhood was defined by experiences in the natural world centering around deep, dark places. Quarries, caverns, and caves. Lawrence heard the echoes and whispers of the dark gods of the earth in those places, and never forgot them. Only in the sense that for Lawrence, it was enough to recognize the presence of those chthonic forces, rather than dedicate his life to delving deeper and deeper into their world, does he differ from Jung.

Lawrence’s main attraction to the Book of Revelations lay in its symbolic and allegorical qualities. Having read widely in the esoteric and occult, although he rightly dismissed Helena Blavatsky’s racist hokum as “not very good,” Lawerence was especially drawn to the pre-Socratics and Heraclitus in particular. The latter’s conception that the universe is governed by battling divine, elemental forces, which both stem from and return to a primary fountain of boundless energy, echoes the cataclysmic struggles of the apocalypse. The essence of the divine is one of constant flux. Creation and annihilation. Most importantly for our purposes, Lawrence’s orientation was never backward looking. His goal was always to discern what could be gained in understanding for the purpose of achieving a reintegration of humanity within the living cosmos. As techno-industrial society appears to triumph, the question becomes more vital than ever: what is the nature of humanity’s relationship to the divinity of the world?

Following Jung, Lawrence saw modern humanity, like the forces of the cosmos, at war with itself. Torn between the rational scientific logic of industrialism and the intuitive religious power of the living world. Just as the former seeks to divide, reduce, and sever, the latter aims toward reintegration and wholeness. Mara Kalnins describes it thus:

Lawrence was keenly alive to the mystery and beauty of the non-human universe and to the sense that the human species is a part of a vast creative pattern. At the same time he saw modern man as willfully divorcing himself from that world through the products of human intellectual consciousness; all too often the quest for material gain and technological advance violate the integrity of the world of nature.

And if the apocalypse is a metaphor for Lawrence’s conception of restoring the integrity of the world and humanity’s place in it, we may find that our current situation, though it is a far less metaphorical kind of cataclysm, may afford us a similar opportunity. Ultimately, Lawrence’s position argues for a rejection of rationality and science in order to rediscover the brightness of the noumenal world and our place in it.

Early in Apocalypse, Lawrence writes “I would like to know the stars again as the Chaldeans knew them...but our experience of the sun is dead, we are cut off. All we have now is the thought-form of the sun. He is a blazing ball of gas.” The pre-industrial world finds the universe vibrantly alive with spiritual power. By denying the animistic essence, the souls in all things, we are left with a world that is deprived of beauty and meaning. Again, this is ultimately the tragedy we face. Not a dead world but a world that never truly lived. A universe of molecules and matter swirling about according to mathematical models and equations. We are left with a view of the cosmos that is consistent with the earth that we have created: lifeless and mechanistic. Oceans of plastic. Poison in the air, water, and dirt. Lawrence: “The Chaldeans described the cosmos as they found it: magnificent. We describe the universe as we find it: mostly void, littered with a certain number of dead moons and unborn stars, like the back yard of a chemical works.” But of course, and herein lies it all, it is not the world that has changed. Only our perception of it. The stars still burn and dance with the sacred fire. But in denying the soul of the world, we have only made ourselves blind to the only thing that makes life worth living. We cannot return to a time before industrialism. We cannot forget the horrors that a mechanized view of the universe has unleashed. But perhaps we can restore something of what has been lost, by reconsecrating ourselves to the living god of the world.

What Lawrence foresaw for this severed humanity was a state of suicide, both for the individual and the collective. In this present moment, it is very difficult to see that he was wrong. It is clear that humanity will choose death over meaninglessness. A world dominated by techno-industrial society is not worth living in. As Lawrence observes, humanity would gladly extend this suicide to the cosmos themselves, if it had the power. This again, is all too clear in the 21st century. Death is not the enemy of life, but godlessness. The despair of humanity today is the product of centuries worth of both the denial of the spiritual life of the world and the suppression of the natural urge to reintegrate with that world. Can one imagine the sort of tortures required to break down the most fundamental impulse within a living thing, to be connected with the whole? Sadly, it is likely that we all have some sense of what that feels like now. Hundreds of years worth of denial cannot expunge what every blade of grass and drop of water knows. So we bury it within ourselves, and as Jung has observed, we trade the living gods of the old world for the psychotic demons of this world.

Nevertheless, despite all of this, there is an optimistic tone to Lawrence’s Apocalypse. A grim kind of optimism, perhaps, but optimism no less. For when things come crashing down, there is the potential for growth, for change. While it might be tempting to see our crisis as a final crisis, we must not forget that this is the linear view of history and time promoted by the rational mind. The end is never really the end. Time is cyclical and destruction brings creation. As Mircea Eliade puts it: “myths describe the various and sometimes dramatic breakthroughs of the sacred (or the ‘supernatural’) into the World.” The apocalypse is one such moment. As structures collapse, a door appears for the old gods to re-enter our world. By losing ourselves in the noumenal world, we are able to break free from the profane world. Mythic time, bursting with spirit and life, repeats itself over and over again. The moment of crisis opens up a world of possibilities. Our present moment shows us plainly what we have lost and what must be restored. This is the true meaning of apocalypse for Lawrence, it shows us

the things that the human heart secretly yearns after. By the very frenzy with which the Apocalypse destroys the sun and the stars, the world, and all kings and all rulers, all scarlet and purple and cinnamon...we can see how the apocalyptists are yearning for the sun and the stars and the earth and the waters of the earth.

We know what truly matters to us when we see it dashed to fragments before our very eyes. As yet, techno-industrial humanity is so far from even acknowledging its true pain. The crisis has evidently not reached a dire enough threshold. Perhaps we can perceive here and there a sort of blind grasping, which appears as despair more often than not. The more suicidal we become, the closer we are to crying out for what we truly want. What will it take, we might ask, for humanity to recognize that what it has lost is wholeness itself. Lawrence writes, “We ought to dance with rapture that we should be alive and in the flesh and part of the living, incarnate cosmos. I am part of the sun as my eye is part of me. That I am part of the earth my feet now perfectly, and my blood is part of the sea.” But as long as we deny a cosmos that is alive, there will be nothing for us to be a part of.

Deny the spirit of the world and we deny ourselves. That in the process we will also bring death and ruin to the earth goes without saying. The rational, scientific mind drives us over this cliff, no longer tethered at all to the earth, intuition, and religion. It is the enemy of the universe, it is the architect of time. No more cycles, no more birth and death. A flaming arrow into the dark void of space. All things shall end, once and for all. And the light will go out of the universe. Lawrence:

How they long for the destruction of the cosmos, secretly, these men of mind… How they work for its domination and final annihilation! But alas, they only succeed in spoiling the earth, spoiling life, and in the end destroying mankind, instead of the cosmos. Man cannot destroy the cosmos: that is obvious. But it is obvious that the cosmos can destroy man. Man must inevitably destroy himself, in conflict with the cosmos. It is perhaps his fate. Before men had cultivated the Mind, they were not fools.

Techno-industrial society is a war against the universe, against the gods, against life. Its dreams and aims are nothing less than an end to all things. But this an illusion. Several hundred years of technological advancement has given some the hopes that their mad fantasies can be achieved. Thankfully this is not the case. Lawrence ends his text with the following words: “What we want is to destroy our false, inorganic connections, especially those related to money, and re-establish the living organic connections, with the cosmos, the sun and earth...Start with the sun, and the rest will slowly, slowly happen.” Find the living gods of the world once again and restore the cycle of time. Profane time will always give way to sacred time.

Death is not the enemy of life, but godlessness.

Ramon Elani

Ramon Elani holds a PhD in literature and philosophy. He is a teacher, a poet, a husband, and a father, as well as a muay thai fighter. He wanders in oak groves. He casts the runes and sings to trolls. He lives among mountains and rivers in Western New England

More of his writing can be found here. You can also support him on Patreon.