In the Terreiro of Old Black Iaiá, Let’s Saravá

On Paganism of the African Diaspora (From Karina Ramos)

English Translation here.

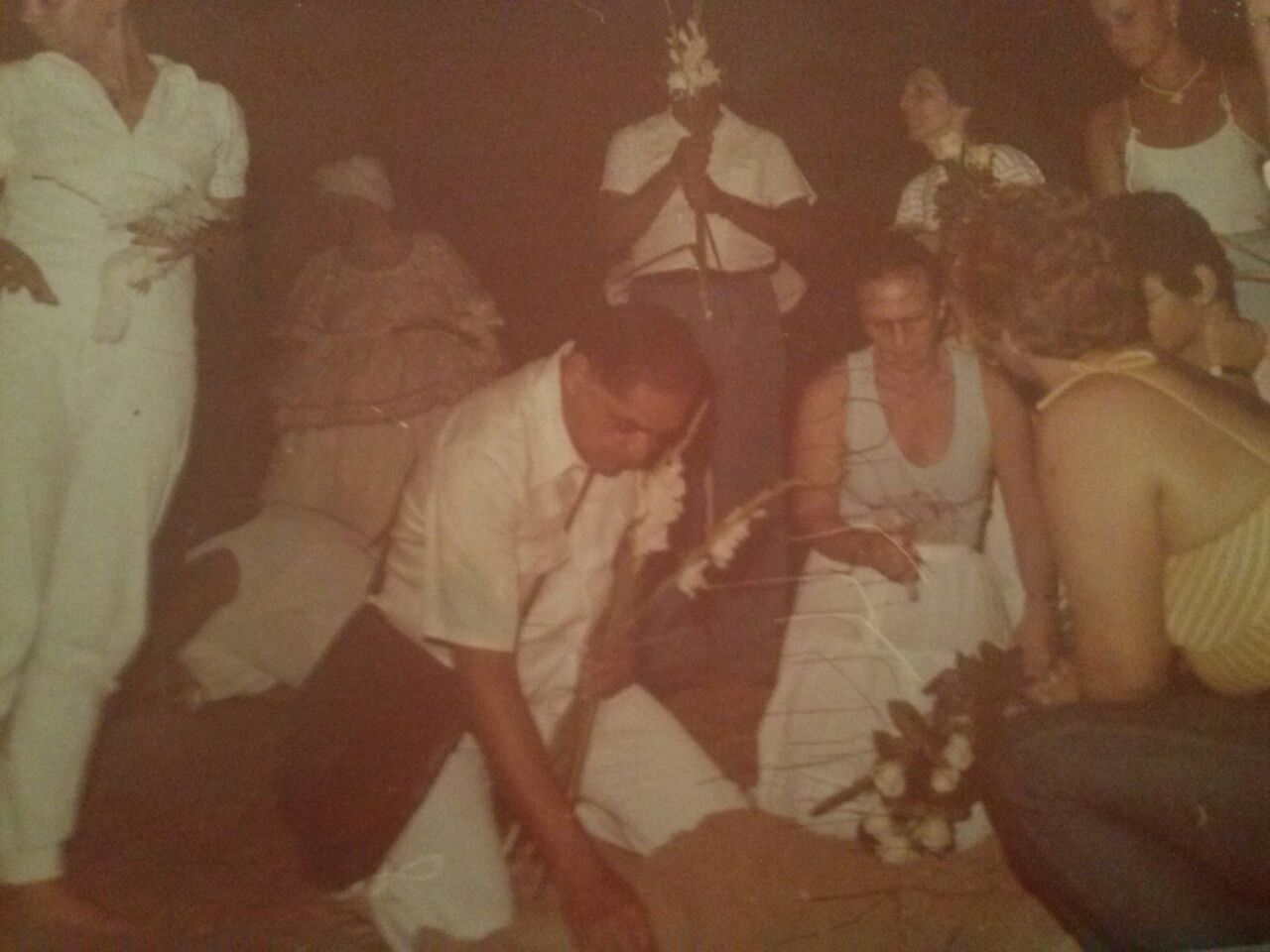

Foto de Laura Cantal

No Terreiro de Preto Velho Iaiá, Vamos Saravá

Aproximadamente no segundo semestre de 2017, os escandalosos ataques sofridos pelas religiões de matriz africana na região metropolitana do Rio de Janeiro ganharam espaços em diferentes mídias. Foram cerca de três meses de noticiamento, em que representantes de diversas frentes políticas, sociais e intelectuais discutiram em torno do acontecimento. Houve, inclusive, a cobertura da 10ª Caminhada em Defesa da Liberdade Religiosa, na qual membros e líderes de diferentes religiões deram as mãos contra a opressão sofrida. Até que, com o correr do tempo, outras informações aterraram a causa e os efeitos desse fenômeno. Não é à toa que, em vista do desenvolvimento do jornalismo moderno, a notícia seja compreendida como ícone do tempo presente e desapareça como fumaça no vento. Mas, convenhamos, não há novidade tampouco efemeridade nos ataques sofridos às religiões de matriz africana. É um acontecimento histórico e que, atualmente, ganha magnitude e feições assustadoras.

O Rio de Janeiro, entre as mais de três décadas de comércio escravagista, recebeu cerca de 3 milhões de africanos escravizados, dentre os quais aproximadamente 1/3 deles desembarcaram no Cais do Valongo na região portuária da cidade – espaço que, em virtude de muita luta, recebeu o título de Patrimônio Mundial pela UNESCO em 2017. Isto precisa ser dito, para início de conversa, porque não há como se conceber o Rio de Janeiro sem se levar em consideração a presença e as manifestações culturais desses 3 milhões de negros africanos escravizados. O Rio de Janeiro é uma cidade maravilhosa também graças ao contributo desses homens e mulheres, sem os quais o samba carioca não haveria existido. Assim como o samba, as chamadas religiões afro-brasileiras são manifestações culturais de matriz africana que, ao longo do tempo e das articulações culturais, construíram uma cara própria: a cara do Rio. Pixinguinha, grande compositor carioca do nosso passado e a quem devemos a chamada deste artigo, é resultado do caldeirão rítmico apenas encontrado nos morros e terreiros cariocas como a lendária Casa da Tia Ciata, terreiro de candomblé frequentado por ele e outras personalidades do samba como Donga e João da Baiana.

Infelizmente, Pixinguinha, Donga e muitos outros homens e mulheres negros e anônimos sofreram e sofrem opressões que remontam a história da cidade. Desde início do século XX, os espaços de sociabilidade e as manifestações culturais de matriz africana são atacados, homens e mulheres negras são expropriadas de seus direitos e de suas condições mais básicas de existência. Não há um intervalo de tempo dentro da linha dos acontecimentos na história do Rio de Janeiro em que os negros e a suas manifestações culturais não tenham sofrido com o poder público. De acordo com a pesquisa realizada pelo historiador Nireu Cavalcanti, entre 1910 e 1918, 66 terreiros espalhados pela cidade foram perseguidos e posteriormente tiveram suas portas fechadas. E isto é uma constante ao longo das décadas seguintes. A interface entre intolerância religiosa e tráfico – esse poder supostamente paralelo e que de paralelo não tem nada – é atualmente a nova forma de opressão que os terreiros têm sofrido, especialmente no estado do Rio de Janeiro.

De acordo com as notícias que temos, nesta década os primeiros casos neste perfil remontam o ano de 2013, quando traficantes evangelizados proibiram que líderes religiosos praticassem os seus rituais, expulsando-os de suas comunidades na Zona Norte da cidade. Segundo as informações do Ministério dos Direitos Humanos, o número de denúncias de injúrias por preconceito religioso subiu de 15, no ano de 2011, para 759 em 2016. Apenas entre agosto e outubro de 2016, foram registradas 42 denúncias de intolerância religiosa no estado fluminense, dentre as quais 38 referem-se às religiões de matriz africana[1]. Para além das imprecisões estatísticas, ainda de acordo com as declarações fornecidas pelo secretário estadual de Direitos Humanos, Átila Nunes, há uma lacuna no código penal, não permitindo uma tipificação clara sobre o que seria considerado preconceito religioso, permitindo que qualquer tipo de agressão aos terreiros possa ser entendido, por exemplo, como um simples desentendimento entre vizinhos.

Respeitar as diferenças e permitir a livre manifestação dessa diferença não se trata apenas de um princípio constitucional, muito menos de algo que deva ser concedido por alguém. É um principio humano. É e sempre deverá ser muito maior do que as determinações de um Estado e de qualquer poder público. No entanto, no sentido contrário desta liberdade inerente ao ser humano, temos acompanhado uma associação nefasta entre o poder político e a bancada evangélica no Congresso Nacional. E este diálogo não deve ser visto como alheio à essas perseguições religiosas ocorridas não apenas no Rio de Janeiro, mas em diversos outros estados brasileiros como a Bahia e Minas Gerais. Atualmente, a Frente Parlamentar Evangélica (FPE) agrega mais de 100 parlamentares, com expectativa de que em 2018 cerca de 165 parlamentares evangélicos sejam eleitos entre Câmara dos Deputados e Senado.[2]

Suas últimas legislaturas estão envolvidas com projetos como o “Estatuto da Família” (PL. 6.583/2013) que, através de regras jurídicas conservadoras, convenciona a definição de família; também contribuíram com Propostas de Emenda Constitucional como a PEC 171/1993 que justifica a redução da maioridade penal a partir de passagens bíblicas; e têm envolvimento com Projetos de Lei como o PL 4931/2016 do deputado João Campos (PSDB-GO) – vulgarmente conhecido como “Cura Gay” -, cujo o relator é o mesmo do Estatuto da Família, o pastor Ezequiel Teixeira (PTN-RJ), assim como o PL 5.069/2013 que ataca o direito constitucional de mulheres vítimas de violência sexual a terem o devido acesso ao aborto – projeto este encabeçado por Eduardo Cunha (PMDB-RJ), ex-presidente da Câmara dos Deputados recentemente preso por corrupção ativa e passiva, prevaricação e lavagem de dinheiro e que, de acordo com o pedido do Ministério Público Federal, pode vir a cumprir 386 anos de prisão.

Note-se que a maior parte dos parlamentares da FPE advém das igrejas pentecostais, como a Assembléia de Deus e a Igreja Universal do Reino de Deus – cujo um dos mais destacados membros é o atual prefeito da cidade do Rio de Janeiro, Marcelo Crivella (PRB-RJ). Este que, entre silenciamentos e medidas conservadoras, não apenas desconsidera a redemocratização do nosso Maraca, como também negligencia a expressão do samba e do próprio carnaval, alma da cidade, uma típica comemoração arduamente construída pelas comunidades e terreiros dos morros cariocas. Outros “grandes” nomes avultam esse relacionamento amoral entre política e religião, como o deputado federal Marco Feliciano (PSC-SP) e o deputado federal Jair Bolsonaro (PP-SP), pré-candidato às eleições presidenciais de 2018.

Ainda que os parlamentares evangélicos pentecostais se afigurem como maioria, não podemos ignorar que há outros atrelados a diferentes vertentes da religião cristã, como os protestantes históricos e os batistas. No entanto, ainda que respeitemos as diferenças entre uns e outros, isto não minimiza o quão inconcebível é que um Estado constitucionalmente laico permita a simbiose entre política e religião tal como temos visto no Brasil. Como anteriormente dito, religião é uma manifestação cultural, própria de uma cultura específica e o direito ao culto, seja ele qual for, deve ser preservado em um Estado Democrático de Direito. Sob nenhuma hipótese pode uma religião ter os seus princípios fundamentais como norteadores das deliberações do poder público, muito menos subverter esses mesmos princípios e cooptar uma massa majoritariamente negra que vive há séculos no abandono, submetida aos mandos de um poder “paralelo” que é igualmente subproduto das artimanhas desse projeto Universal.

A Origem Desse “Big Bang”

A gênese de todo esse enredo, ao meu ver, parte da ideia de que os princípios de liberdade e igualdade foram há muito tempo adulterados em função da orquestração do poder entre os homens. Não encontro absurdo algum em afirmar categoricamente que o entendimento de mundo e de relação com o outro que nos foi introjetado tem direta conexão com a lógica de uma parcela de homens que, partindo de seus interesses políticos e econômicos, quis imperar. Sim, faz parte de um projeto ambicioso. E, pior, faz parte de um projeto maléfico e que, infelizmente, segue vigente até os dias de hoje, assumindo formas variadas ao longo da história.

Poderíamos aqui discorrer sobre as suas origens em um movimento de reconstrução histórica, mas é provável que nos percamos em tantas idas e vindas. De qualquer forma, importa expor a sua pedra angular, uma vez que ela ainda hoje limita a nossa existência enquanto sociedade e, acredito eu, seja essa a pedra no sapato que causa grande parte das atrocidades no mundo. O modelo de construção desse mundo particular pode ser entendido como “paradigma da simplificação”[3]. E ele traz em sua gênese o princípio da disjunção e da redução da realidade humana a partir de uma perspectiva eurocêntrica, falocêntrica e colonialista.

A igualdade entre os homens foi abstratamente construída através de um suporte jurídico-moral baseado nesse paradigma. O direito a existência da multidiversidade cultural da espécie humana é automaticamente negado, sendo a nossa natural diferença cultural enquadrada em noções hierarquizantes. Aqueles que não são considerados iguais passam a ser considerados como passíveis de opressão. O conservadorismo que esse modo de ver o mundo instaura, enquanto filosofia política e social, é portanto necessariamente racista e misógino. Ele é contrário a prática democrática de coexistência das diferenças.

Em sua evolução, de forma ainda mais cruel, esse paradigma serviu de base para um sistema econômico que, devido a sua própria natureza, compreende o mundo como um produto. Ou seja, o capitalismo – que hoje se embrenha e rege a lógica das relações humanas – é um sistema que compreende o mundo e os seres humanos como produtos a partir de uma ótica disjuntiva e inerentemente racista e misógina. Mulheres, homossexuais, crianças, idosos, negros e uma série de outras categorias são vistas como subprodutos. É essa a base do sistema vigente que é responsável pelo desmantelamento dos vínculos sociais que garantiriam a nossa existência.[4]

Ele desconsidera todas as variadas formas de existir, todas as formas de auto-reconhecimento e de valorização da essência própria de cada ser humano no mundo. No meu entendimento – que também se constrói a partir da minha vivência e experiência de vida – o candomblé e todas as religiões de matriz africana são mais uma forma de existência e de compreensão do mundo. Mas não se trata apenas de uma representação a partir de uma cosmogonia sui generis, cujas bases históricas encontramos em diversas comunidades infelizmente desmanteladas em toda a África. As religiões de matriz africana são um meio de se compreender a vida social de maneira mais elevada, assim como toda religião deveria ser e ser exercida. Elas são um modo de vida e de entendimento dessa existência. Elas permitem que, ao reconhecer a sua ancestralidade e sua história, seus fiéis valorizem a sua essência e compreendam o valor da cultura que as originou.

Tendo sido nascida e criada em um terreiro de Candomblé da família do Axe Pantanal cujas origens nos levam à Bahia, atesto 30 anos de vivência em uma comunidade que, como outra qualquer, tem seus rituais e sentidos particulares, mas que em nenhum momento deixou de exercer a função de acolhimento e de auxílio na integração social de seus membros. Há mais de 20 anos que as insígnias do terreiro da minha casa foram retiradas, assim como seus atabaques – responsáveis pelo ritmo e pelos ensinamentos ancestrais que palavras não traduzem – foram guardados por medo de possíveis perseguições. Minha mãe pediu que seus filhos não trafeguem vestidos com as roupas brancas e expondo seus fios de conta – colares feitos de missança e pedras específicas que representam os Orixás – por medo de qualquer tipo de agressão por parte dos vizinhos que são, como em quase toda comunidade do subúrbio carioca, majoritariamente evangélicos.

Mas minha casa continua sendo a casa de uma família que ultrapassa a dimensão normativa imposta pelo pensamento propalado pelo paradigma da simplificação. A minha casa não compactua com a intolerância, muito pelo contrário, ela carrega ensinamentos ancestralísticos que afastam a ignorância – moeda muito valiosa entre os pentecostais que estão no Congresso. Minha casa é organizada – e não dominada – por uma matriarca, por uma mulher que recebe, aceita e orienta qualquer ser humano que entre portão adentro, independentemente de qualquer padrão imposto pela sociedade e os dignifica, fazendo com que eles acreditem em seu potencial. É uma casa soberana. É uma família não convencional que professa uma fé e independe do poder público. Observando-se como se estrutura o poder, não é difícil entender o “perigo” que, assim como outros tantos terreiros, minha casa representa para um mundo em que a carne mais barata é a carne negra.

Rodapé:

[1] Fonte: Secretaria de Estado de Direitos Humanos Políticas para Mulheres e Idosos (SEDHMI). Informações obtidas em reportagem do Jornal O Globo, 05/11/2017.

[2] Informações obtidas aqui.

[3] O conceito é elaborado pelo antropólogo Edgar Morin. Seu estudo epistemológico compreende a relação dos pressupostos da ciência com a sociedade, relação esta que teria o poder de influenciar a construção do mundo social a partir do paradigma da simplificação. Ver M ORIN. Edgar. Introdução ao pensamento complexo. Lisboa: Instituto Piaget, 1992.

[4] De acordo com os relatórios da Oxfam, a riqueza acumulada pelo 1% mais rico do mundo corresponde a riqueza dos outros 99% restantes. E 9 entre cada 10 indivíduos mais ricos são homens e caucasianos. Para mais, ver Oxfam.

Nota da editora: Imagens não creditadas são cortesias da escritora, e pertencem ao seu acervo pessoal. Por favor, não reproduzir ou apropriar antes de pedir permissão.

Karina Ramos

Nascida e criada em um terreiro de Candomblé na Zona Oeste do Rio de Janeiro, Karina Ramos é historiadora, especialista em história da África contemporânea.

Photo by Laura Cantal

In the Shrine of Old Black Iaiá, Let’s Hail

Approximately in the second half of 2017, the scandalous attacks suffered by ancestral-African religions in the metropolitan region of Rio de Janeiro gained much space in the media. It was about three months of reporting, in which representatives from various political, social and intellectual fronts discussed the event. There was even the coverage of the 10th Walk in Defense of Religious Freedom, in which members and leaders of different religions joined hands against the oppression. Until, over time, more information appalled the cause and effects of this phenomenon. It’s no wonder that, in view of the development of modern journalism, the news is understood as an icon of the present time, and disappears like smoke in the wind. But, let’s face it, there is neither novelty nor ephemerality in the attacks on ancestral-African religions. It is a historical event and it is now gaining magnitude and scary features.

Rio de Janeiro, among more than three decades of slave trade, received about 3 million enslaved Africans, of whom about 1/3 of them landed at the Valongo Pier in the port area of the city – a space that, because of much struggle, received the title of World Heritage by UNESCO in 2017. This needs to be said in the first place because there is no way to conceive Rio de Janeiro without taking into account the presence and cultural manifestations of these 3 million enslaved black Africans. Rio de Janeiro is a wonderful city also thanks to the contribution of these men and women, without whom Rio’s sambawould not have existed. Like samba, so-called Afro-Brazilian religions are African cultural manifestations that, over time and from cultural articulations, have built their own face: the face of Rio. Pixinguinha, the great Rio de Janeiro composer of our past and to whom we owe the title of this article, is the result of the rhythmic cauldron only found in Rio’s morros (hills where there are favelas) and terreiros (yard-like shrines) such as the legendary Casa da Tia Ciata, a Candomblé terreirofrequented by him and other samba personalities like Donga and João da Baiana.

Unfortunately, Pixinguinha, Donga, and many other black and anonymous men and women have suffered, and still suffer oppression that dates back to the city’s history. Since the beginning of the 20th century, spaces of sociability and cultural manifestations of African matrix are attacked, black men and women are expropriated of their rights and their most basic conditions of existence. There is not an interval of time within the line of events in the history of Rio de Janeiro where blacks and their cultural manifestations have not suffered with public power. According to research conducted by the historian Nireu Cavalcanti, between 1910 and 1918, 66 terreiros scattered throughout the city were persecuted and later had their doors closed. And this is a constant throughout the following decades. The interface between religious intolerance and trafficking – this supposedly parallel power that has nothing at all – is currently the new form of oppression that the terreiros have suffered, especially in the state of Rio de Janeiro.

According to the news that we have, in this decade the first cases in this profile go back to the year 2013, when evangelized traffickers prohibited religious leaders from practicing their rituals, expelling them from their communities in the North Zone of the city. According to information from the Ministry of Human Rights, the number of complaints of religious prejudice increased from 15 in 2011 to 759 in 2016. Only between August and October 2016, 42 complaints of religious intolerance were registered in the state of Rio de Janeiro, of which 38 refer to religions of African origin. In addition to the statistical inaccuracies, still according to the statements provided by the state secretary of Human Rights, Attila Nunes, there is a gap in the penal code, not allowing a clear definition of what would be considered religious prejudice, allowing that any type of aggression to terreiros can be understood, for example, as a simple misunderstanding between neighbors.

Respecting differences and allowing the free expression of this difference is not only a constitutional principle, much less something that should be granted by someone. It is a human principle. It is and always should be much greater than the determinations of a State and of any public power. However, in the opposite sense of this freedom inherent to the human being, we have accompanied a nefarious association between political power and the evangelical bench in the National Congress. And this dialogue should not be seen as alien to these religious persecutions that occurred not only in Rio de Janeiro, but in several other Brazilian states, such as Bahia and Minas Gerais. Currently, the Evangelical Parliamentary Front (FPE) brings together more than 100 parliamentarians, with the expectation that in 2018 about 165 evangelical parliamentarians will be elected between the House of Representatives and the Senate.

Their last legislatures are involved with projects such as the “Family Statute” (PL 6.583/2013), which, through conservative legal rules, convenes the definition of family; also contributed with Proposals of Constitutional Amendment like the PEC 171/1993 that justifies the reduction of the criminal adulthood based on biblical passages; and have involvement with Law Projects such as PL 4931/2016 by Rep. João Campos (PSDB-GO) – commonly known as the “Gay Cure” – whose rapporteur is the same as the Family Statute, Pastor Ezequiel Teixeira (PTN- RJ), as well as PL 5.069/2013 that attacks the constitutional right of women victims of sexual violence to have adequate access to abortion – a project headed by Eduardo Cunha (PMDB-RJ), the former president of the Chamber of Deputies who was recently imprisoned for active and passive corruption, prevarication, and money laundering. All of which, according to the request of the Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office, earned him a 386 year sentence.

It should be noted that most FPE parliamentarians come from Pentecostal churches, such as the Assembly of God and the Universal Church of the Kingdom of God – one of the most prominent members being the current mayor of the city of Rio de Janeiro, Marcelo Crivella (PRB-RJ). This, which, amid silence and conservative measures, not only disregards the redemocratization of our Maracanã (the football stadium where the televised carnaval happens), but also neglects the expression of samba and carnaval themselves, the soul of the city, a typical celebration arduously built by the communities and terreiros of Rio’s morros. Other “big” names add to this amoral relationship between politics and religion, such as federal deputy Marco Feliciano (PSC-SP) and federal deputy Jair Bolsonaro (PP-SP), pre-candidate for the 2018 presidential elections.

Although Pentecostal evangelical parliamentarians seem like a majority, we can not ignore the fact that there are others tied to different strands of the Christian religion, such as the historical Protestants and the Baptists. However, even though we respect the differences between them, this does not minimize how inconceivable it is that a constitutionally secular state allows the symbiosis between politics and religion as we have seen in Brazil. As previously stated, religion is a cultural manifestation, proper to a specific culture and the right to worship, whatever it may be, must be preserved in a democratic state of law. Under no circumstances can a religion have its fundamental principles guiding the deliberations of public power, much less subvert those same principles and co-opt a majority black mass that has lived for centuries in abandonment, under the control of a “parallel” power that is equally a by-product of the tricks of this Universal project.

The Origin of This “Big Bang”

The genesis of this whole plot, in my opinion, starts from the idea that the principles of freedom and equality have long been adulterated by the orchestration of power among men. I find no absurdity to assert categorically that the understanding of the world and of the relation to the other that has been introjected to us has a direct connection with the logic of a portion of men who, from their political and economic interests, wanted to rule. Yes, it’s part of an ambitious project. And, worse, it is part of an evil project and, unfortunately, it is still in force until today, taking on varied forms throughout history.

We might here dig into its origins in a movement of historical reconstruction, but we are likely to lose ourselves in so many comings and goings. In any case, it is important to expose its cornerstone, since it still limits our existence as a society and, I believe, is the stone in the shoe that causes much of the world’s atrocities. The construction model of this particular world can be understood as the “simplification paradigm”. And it brings in its genesis the principle of disjunction and the reduction of human reality from a Eurocentric, phallocentric and colonialist perspective.

Equality between men was abstractly constructed through a legal-moral support based on this paradigm. The right to existence of the cultural multidiversity of the human species is automatically denied, and our natural cultural difference is framed in hierarchical notions. Those who are not considered equal are now considered as oppressive. The conservatism that this way of seeing the world establishes, as a political and social philosophy, is therefore necessarily racist and misogynist. It is contrary to the democratic practice of coexistence of differences.

In its evolution, even more cruelly, this paradigm served as the basis for an economic system that, by its very nature, understands the world as a product. That is to say, capitalism – which today stands and governs the logic of human relations – is a system that understands the world and human beings as products from a disjunctive and inherently racist and misogynistic perspective. Women, homosexuals, children, the elderly, blacks and a host of other categories are seen as by-products. This is the basis of the current system that is responsible for dismantling the social bonds that would guarantee our existence.

He disregards all the various forms of existence, all forms of self-recognition and appreciation of the essence of each human being in the world. In my understanding – which is also built from my experience and experience of life – Candomblé and all religions of the African matrix are more of a way of existence and understanding of the world. But it’s not just a representation from a cosmogony sui generis, whose historical basis we find in various communities unfortunately dismantled throughout Africa. African-born religions are a way of understanding social life in a higher way, just as every religion should be and be exercised. They are a way of life and understanding of this existence. They allow, in recognizing their ancestry and their history, their believers to value their essence and understand the value of the culture that originated them.

Having been born and raised in a Candomblé terreiro of the family of Axe Pantanal, whose origins take us to Bahia, I attest to 30 years of living in a community that, like any other, has its own particular rituals and senses, but that at no time stopped exercising the function of reception and assistance in the social integration of its members. For more than 20 years, the insignia of the terreiro of my house have been removed, just as their atabaques – the percussion responsible for the rhythm and for the ancestral teachings that words do not translate – were kept for fear of possible persecution. My mother asked her children not to wear white clothes and expose their fios de conta – necklaces made of beads and specific stones representing the Orixás – for fear of any kind of aggression on the part of the neighbors, who are, as in most of Rio’s suburban communities, predominantly evangelical.

But my house remains the home of a family that goes beyond the normative dimension imposed by the thinking propounded by the simplification paradigm. My house does not cope with intolerance, on the contrary, it carries ancestralistic teachings that drive away ignorance – a very valuable coin among the Pentecostals in Congress. My house is organized – not dominated – by a matriarch, by a woman who receives, accepts and directs any human being who enters the gate, regardless of any standard imposed by society, and dignifies them so that they believe in their potential. It is a sovereign house. It is an unconventional family that professes a faith and is independent of the public power. Observing how power is structured, it is not difficult to understand the “danger” that, like so many terreiros, my house represents for a world in which the cheapest meat is the black meat.

Footnotes:

[1] Source: Secretariat of State for Human Rights policies for women and the Elderly (SEDHMI). Information obtained in report of the newspaper O Globo, 05/11/2017.

[2] Information obtained here.

[3] The concept is drawn up by anthropologist Edgar Morin. His epistemological study understands the relationship of the assumptions of science with society, this relationship that would have the power to influence the construction of the social world from the paradigm of simplification. See M ORIN. Edgar. Introduction to complex thinking. Lisbon: Piaget Institute, 1992.

[4] According to Oxfam’s reports, the wealth accumulated by the world’s richest 1% corresponds to the richness of the remaining 99%. And nine out of ten richest individuals are men and Caucasians. For more, see Oxfam.

Editor’s note: Non-credited images are courtesy of the writer, and part of her personal collection. Please do not reproduce or appropriate without permission.

Translator’s note: Words in italics are left untranslated due to the inadequacy of their closest English counterparts. By leaving them as is, we hope to introduce them into the English linguistic repertoire.

Term Index

Atabaque: A holy percussion instrument used in the ceremonies, where the rhythm and dance are vessels to divine ancestors.

Bahia: A state in the Northeast region of Brazil. It was the first point of contact the Portuguese had with what became the Brazilian colony. Its capital, Salvador, was Brazil’s first capital. It’s now the city with the most African descendants outside of Africa (an estimated 80% of the population). Though difficult to cite precisely, Salvador’s port was one to receive the most enslaved Africans (Rio de Janeiro being second). Only in the second half of the 1700’s, almost one million Africans came to Brazil, half of which came to Salvador (the others to Rio and other parts of the coast). Of the almost 5 million total enslaved Africans that came to Brazil during the nearly 500 years of Colonialism, Salvador is undoubtedly the city most affected by this horrific event in history, a legacy and a reality that is still very much alive today.

Candomblé: An ancestral African Religion of the African Diaspora, worshippers of Orixás.

Carnaval: A Christian festival celebrated in February. A particularly epic event in Brazil, where people drink excessively, hook up, and watch Samba “schools” (teams/groups) perform and compete against each other in massive moving trucks with dancers, musicians, props, and costumes.

Favela: A type of slum formed in response to rural exodus (into large cities e.g. Rio and São Paulo), and to over-population, homelessness, lack of infrastructure and social services. Favelas developed into well organized autonomous regions that operate in parallel to the governmental system. They have a parallel economy, infrastructure and security systems, often maintained by trafficking/traffickers.

Fios de conta: Necklaces representative of the Orixás, made of beads and stones of the symbolic color of each divine ancestor, held together by a cotton thread (never by synthetic nylon threads).

Maracanã: Was once the largest football stadium in the world, site of legendary World Cups and football history moments. It is also where the televised Carnaval parade happens.

Morro: A hill where there is a favela. Favelas first started forming in hills because they were a sort of terrain unaccounted for by the State or land owners.

Samba: A Brazilian musical genre bred in Rio de Janeiro, with rhythm and dance deriving from African roots in Bahia.

Orixás: Divine African ancestors. They represent Nature’s forces and have human-like characteristics such as personality, image and emotions. They are also expressed through color symbolism. Due to Colonial oppression, these Orixás were in some instances merged with the figures of Catholic saints as a self-preservation and disguise strategy.

Terreiro: Where Afro-Brazilian Religious cerimonies happen, and where offerings are given to Orixás. It can be described as a sort of shrine, except there is not construction, only an enclosed open space.

Karina Ramos

Born and raised in a Candomblé terreiro in the West Zone of Rio de Janeiro, Karina Ramos is a historian, an expert on the history of contemporary Africa.