A Standing Rock Story Part 1

"I’ve owed Rhyd a post for well over a year. Not just one post. Lots of posts. I’m sorry this has taken so long. I hope that you’ll understand why it’s been so hard to get this first one written…" From Eli Sterling

By Tim Yakaitis

It’s been a year and a half since I packed my van for a camping trip and headed east to the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. There were thousands of people camped there to stand up for indigenous treaty rights and to stop the construction of the Dakota Access Pipe Line (DAPL) through sacred grounds and across the Missouri River. In a matter of months, an empty field between the 1806 highway and the Missouri river had turned into a bustling village of tents, RVs and tipis. There was no mains electricity, no running water save for the cannonball river and the Missouri herself, no Internet fiber, and precious little cell phone reception. People from over 300 tribes across the Americas and beyond were gathered there in this perfect example of a “low resource situation” and I was headed there to see how the community of Geeks Without Bounds could help the community in the #NoDAPL camps with their infrastructure needs.

The funniest thing of all is that one year ago, just a month after returning to my apartment in Washington state after two seasons in the land of The Great Sioux Nation, I thought that the experience hadn’t really changed me much. It wasn’t until May when I met up with fellow Water Protectors at UC Santa Barbara’s “Standing Rock in Santa Barbara” event that I realized how much I’d been reshaped by the fires of Oceti Sakowin.

It’s hard to write about those changes now, hard to know where to start and how to organize all the pieces so that they will make sense to someone who wasn’t there. I don’t want it to seem like I’m telling “the story” of anything. I’m telling my story. I’m sharing the things that I learned. When we were exiled from the camps by the colonialist government authorities, the Native elders told us to go back to our communities and continue the work. They told us to remember to keep praying. They told us to tell the stories of what happened. They told us to keep fighting for our Mother Earth and for the Water and for All Our Relations.

October 2016

From the outside, the world saw Standing Rock as a protest. From the inside it was a community and a family. While many people who spent time in that village would call themselves capitalists or might tell you that they believe in the rightness of capitalism, I will tell you that the very existence of the camps and the way they functioned was anti-capitalist, anti-extractivist, and anti-colonial. Money and goods were tranvested from the capitalist over-culture and absorbed into a space where human needs were met simply because they were needs and where work was done because we cared about each other and because we cared about the Earth we live on.

This would-be idyllic existence was marred by the fact that we were in the middle of a war. It was a surreal war, completely asymetric, where the capitalists tried to prove how right they were through the use of intimidation, misinformation, guns, pepper spray, water cannons, airplanes, helicopters, and an assortment of illegal activity. Meanwhile, the local newspapers and the conservative press called us “law breakers” and sometimes even “terrorists”. We had to pass through road blocks manned by the National Guard or drive more than an hour around them. Law enforcement mobile command centers sat by the side of the road near by, sometimes two or even three together.

Our side of this war was not fought with guns. It was fought with prayer and Facebook livefeeds. There was prayer every morning and every night. There was prayer before every meal. There were sweat lodges every day, and sacred fires that burned without stop. The outside world heard about us through social media and they flooded us with support. People showed up by the thousands and those who couldn’t come sent donations.

I keep talking about “us” and “we”, identifying myself as one of the Water Protectors, but it didn’t start out that way. I was certainly moved to help the NoDAPL movement, but when I arrived I did not see myself as part of the community. I was just there to assist with the tools and resources I had available. I thought I was just going for two weeks to set up an Internet connection in collaboration with a member of the Lenca Nation of Central America. By the time I had been there two weeks I discovered that I wasn’t there just for “them”. I was there for “us”.

I was at Standing Rock for all the people who drink water that has been poisoned by industry and for those whose water we hope to protect from such a fate. I was there for all the people who have had their land and livelihood taken away from them, whether through the enclosures in Europe, the settlers and Manifest Destiny in America, or by banks and governments today. I was there for people who have been told that clean water is not a right, that medical care is for those who can afford it, that housing is something you must pay a third or half of your income for monthly, that healthy food is the most expensive kind, and that your neighbors are dangerous criminals who will steal your things and abuse your children. I am one of those people, so like it or not, I was there for myself.

I didn’t come to that conclusion by myself, though. All of us who were there were invited. The elders knew that we are all bound together on this Earth. They knew that we all drink the same water. They knew that by standing together on sacred ground, joining the prayers of all our peoples together, we would effect a change inside ourselves and in the world around us. There were many times when I heard an elder say, “We even invite the infiltrators to be here with us. Let them come! Let them see what’s happening here! Even if they are against us now, they will be changed. This is their water, too.” And they were right. Some of the infiltrators from those days have become whistleblowers. The power of all that prayer moved things in everyone.

Oceti Sakowin

Oceti (say oh-CHEH-tee) means “camp fire” in the Lakhota language. Sakowin (say shock-oh-WEEN) means “seven”. Together, they are the Seven Council Fires of the Lakota people. The Lakota are one of the three parts of what is known as the Great Sioux Nation in English today. The other two parts are the Nakota and the Dakota. All three names mean “friend” or “ally” in their respective dialects.

When the first Water Protector camp started up at Standing Rock in April 2016, it was at Sacred Stone which is located on the Standing Rock (Hunkpapa) reservation, just south of the Cannonball River and west of the Missouri. By June of 2016 some people had moved out of Sacred Stone and onto a large open field to the north of Cannonball river. This was not in the modern boundaries of the Standing Rock reservation, but it was part of the original treaty territory that was to belong to The Great Sioux Nation. This new camp was on land where the Seven Council Fires had met 140 years before. They came together once again for the matter of their sovereignty and protecting the sacred land and water, and so the camp was named Oceti Sakowin in respect of that historic gathering.

After December 5th, some people started calling the camp “Oceti Oyate”, which was meant to mean “Council Fire of the People”. In modern usage, Oceti can also mean “stove” in some dialects, and so one elder declared that this name actually fit the camp pretty well since we were the “People of the woodstove” that winter.

Many of us who were at camp for a long time now simply call the camp “Oceti” unless we are speaking specifically of the section of the camp where the Seven Councils met (called The Horn), the sacred fire that was in that place, or the continuing work of that joint council.

There was another camp on the south side of the Cannon Ball river called Rosebud or Sičangu (say See-CHAN-goo). That camp was organized by the Sičangu band of the Lakota from South Dakota, and it had it’s own kitchen, sacred fire, sweat lodge, tent sites, security detail, and so on. In discussions of coordination and internal politics it was considered to be part of Oceti Sakowin or completely its own camp depending on context.

For many months at Oceti, there was a meeting every morning at 9am where people could learn about what was happening around camp, voice their concerns, and coordinate working teams throughout the camps. That meeting was facilitated by Johnny Aseron from the Cheyenne River reservation, but for one week in November when he was sick, I had the privilege of facilitating the 9am meetings at the Dome. By that time there were literally hundreds of new people showing up to the camp every single day. Some would stay for just a few days, but most would show up at the Dome on the morning after they arrived for the 9am meeting and orientation.

When Johnny led the meeting, he would take a few moments before sending the newbies off to orientation to say hello and give them a few words about where they were. On the days that I led the morning meeting, I had my own spiel for the newcomers:

“This camp is called Oceti Sakowin. Oceti means camp fire. Sakowin means seven. This refers to the Seven Council Fires of the Lakota people, and it is also the name for the Lakota/Dakota/Nakota Nation, what the US government calls ‘The Great Sioux Nation’, in their own language. You are on treaty territory. You are in the land of The Great Sioux Nation. If you’ve never been outside the United States before, congratulations! You, like me, are here on a special visa waiver program. We have all been invited by the Lakota people to be here with them at this historic moment, but do not forget that you are not in the United States any more. You are in a foreign country. Treat the people and the culture with the respect that you would do in any other country that you visited.”

October 2016

Arrival

Before I even got to camp, the Oceti Synchronicities had begun. My friend Roberto Monge had some friends from his town who had just been at camp and were heading back home at the same time I was heading towards Standing Rock. He introduced us via email and text message and suggested we should meet up somewhere on the road. They contacted me and suggested we meet up for dinner in Billings, Montana. My day got off to a bumpy start, though, and I didn’t even get on the road until about 3 in the afternoon. It turned out that they also didn’t get into Billings when they expected, so at 11pm we all agreed to meet up for breakfast in the morning.

As I rolled into Billings at 3 in the morning, I wondered where they had gotten off the highway for the night. There are three highway exits, and I had no way of knowing which one they were closest to. I picked one at random and began to look for a safe place to park my van, make my bed and go to sleep. As I turned a corner I saw an outdoor sports chain store that is known to let people in campers and RVs sleep in their parking lots. I pulled into the parking lot, climbed into the back of my van, set up my bed, set my phone alarm for 6am, and caught 3 hour’s of sleep. When my alarm went off, I sent a text message to the people I was trying to meet up with. A moment later they texted me back with their hotel address. It was a directly across the street from where I was parked.

I pulled into the hotel parking lot, went in to the breakfast room, and sat with my new friends. They drew me a map of the camps and told me how to get there. They showed me where they had been camping, tucked back into a grove of trees which protected it from the harsh winds. They gave me names of people that they had met, and suggested other people that I should contact when I arrived. Their 30 minute orientation between bites of waffle gave me everything I needed to know before Roberto showed up with the equipment to set up the Internet a few days after me.

That evening I got to Bismark, North Dakota about an hour before dusk. There was a conference call with Roberto and some other friends of his to discuss their arrivals, things they would bring, and what we each needed to do. I knew that there was no cell coverage in the camps, so I pulled over into a parking lot for the call before heading south on 1806.

About 10 minutes south of Bismark I arrived at the police check point. I say police, but it was really manned by several national guardsmen in army uniforms and carrying their rifles. I say checkpoint, but it was more of a road block, or like an Israeli military checkpoint in the West Bank. There were concrete dividers that went all the way out to the property fences on each side of the road and that came together in such a way that only one car could go through at a time. This was the first time that the reality of the war zone hit me. This was part of a classic military low intensity conflict strategy.

At the check point a guardsman asked me, “Have you been down this road recently?”

I said, “No.”

“Well, we’re just here to let you know that there are some people camping down the road a little ways here. They may be out walking on the side of the road, so it’s important for you to slow down and watch out for pedestrians, ok?” The soldier was cheerful and friendly.

My complexion is fairly pale, my hair sort of auburn where it isn’t dyed purple, blue or pink. I knew already from reports online that I would not have been allowed to go down this road at all if my skin and hair had been darker.

About 25 minutes later I had arrived at Oceti Sakowin, but it was dark and the driveway entrances were a bit confusing. I was trying to get to the Sičangu camp on the south side of the Cannon Ball river, but I missed the turn off in the dark, drove into the town of Cannonball, following some signs for what seemed like an eternity, and then finally ended up at the Sacred Stone camp way to the east of where I’d meant to be. But it was getting late at that point, and I hadn’t had much sleep. I pulled up to the security gate, told the guards that I had meant to go to Sičangu, but it’s dark and could I sleep there for the night? They said “Welcome!” and pointed the way to a good place to park for the night.

Despite being very tired, I was not quite ready to sleep. I needed to greet the land and the spirits there. I pulled some tobacco out of a large pouch in the back of my van, and put it carefully into a smaller pouch that would fit into my pocket. Then I walked down the hill toward the Cannonball river. There is a path that leads from Sacred Stone over to Sičangu along the river, but it was very dark and the path is shrouded in trees that make it even darker.

I think that night it must have been somewhat overcast, because I don’t remember the stars that night at all. I just remember the river and the muddy path and the trees. I remember walking about halfway between the two camps to a lonesome place where I couldn’t see another human. I felt a bit afraid, like I was going to get lost or trip and fall into the river or like I was going to walk into some place I wasn’t supposed to be. So I stopped right there.

The tobacco in my pocket was for praying. I put my hand in the baggy in my pocket and pulled some out. I stood there with the tobacco in my hand and began to pray. I said thanks for the sun, the moon, land, the sky, the water, the trees, the other plants, the animals, the humans gathered there, for bringing me safely to that place, for making things work out just right that morning in Billings. And then, I took a few breaths and I began to greet the Land and the spirits on that land. I told them who I was and why I was there.

Normally, at this point, I should feel some response from spirit. There should be some sense that I have not been talking to myself, that the spirits I am talking to have heard me. But there was just silence. And darkness. And cold.

I assured the spirits that I would follow the requests and requirements of the people whose land I was on, and that I would also listen to the voices of the the spirits themselves.

I felt cold and fear. I felt distrust aimed at me.

I knew that the spirits didn’t believe what I’d said.

I gave the tobacco to the ground and to the plants. I prayed again, this time telling the spirits that if they were willing to teach and to guide me in the way that I should behave in their land that I was willing to learn. And if they were not willing, I promised to do my bumbling best to be a good guest and a good friend. I said a few words in Lakota, which I had been studying for a few weeks before my trip. I waited in the silence. The spirits were not terribly impressed.

At last, I thanked the spirits and walked back to my van.

As I prepared for bed, I turned my phone to airplane mode and unplugged it from the charger. The battery was at 100%. It should last me for two or three days like that. I set my alarm for 7am and went to sleep.

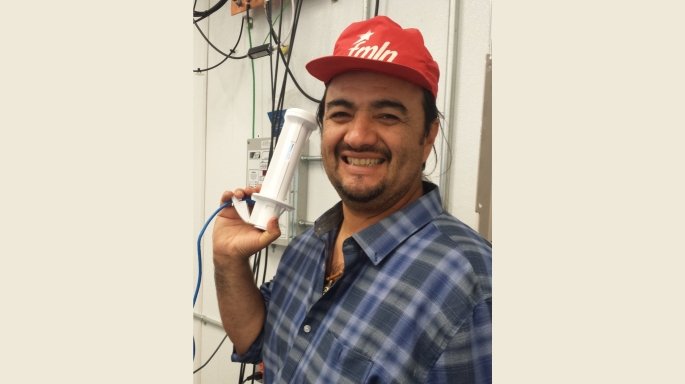

Roberto Monge with antenna for long distance wireless Internet. October 2016

This Is (Cyber) War

The next morning I woke up. I didn’t know what time it was, but the sun was bright in the sky. I pulled up my phone to check the time and see what happened with my alarm. The screen was black. The phone would not turn on. The battery was completely dead.

If the checkpoint had been my first realization that we were in a war zone, this was the moment that I realized that the government was using cyber warfare on us alongside the more traditional fare. This was the moment that it hit me that someone could be using a Stingray device against the Water Protectors.

At first, I wasn’t sure what had caused my battery to drain. The idea that it might be a fake cell tower – also known as an IMSI Catcher, a cell-site emulator, or by the brand name Stingray – was in the back of my head, but one dead phone is not enough to say that was the culprit. These devices are used by law enforcement all over the United States under shady circumstances with questionable legality. At that point I was thinking that maybe my phone had been compromised before I had even arrived at the camps. If I’d gotten some malware onto my phone in the days leading up to my trip, that app could have been trying to ping home over the network even though the network was turned off.

I walked around Sacred Stone that morning, found someone who could tell me what time it was, and mentioned what had happened to my phone. They said that was a common problem. They figured it was because of the lack of cell towers in the area, and I had to agree that for most people, that probably was the cause of their phone going dead. But then someone else overheard the conversation and jumped in. They had also turned their phone to airplane mode and had it die on them.

After breakfast, I headed over to the legal tent on Media Hill (aka Facebook Hill) at Oceti. When I introduced myself, they knew who I was and had been expecting me. I waited for a bit while they handled more urgent matters, and then a few lawyers, a paralegal or two and I sat down to have a chat. Before we even got into the topic of the Internet set up, I mentioned what had happened to my phone and asked if they’d heard of anything like that. They had. That and much more.

Not only had people been complaining about phones going dead overnight, but they said that phones often went dead suddenly as one of the planes flew by overhead. But that wasn’t all. One person at the table had an almost unbelievable story about a car battery dying at night when a plane flew over. And then there were the reports of malware on people’s phones. The most prominent one was Myron Dewey of Digital Smoke Signals. His iPhone would start the voice recording function at seemingly random moments. It wasn’t even secretive. The phone would announce that it was recording, and then the record app would be on the screen.

I listened to these stories and then I asked, “Has anyone called the EFF?”

They hadn’t called the Electronic Frontier Foundation yet, but that day they did. The EFF is a nonprofit organization that defends civil liberties in the digital world. They are like the ACLU for the Internet. The EFF sent a researcher and a lawyer up to the camps a few weeks later, and we worked together to try to determine what exactly was going on. The fact of the matter is that none of us knew exactly.

By the time the EFF researcher arrived, I was convinced that one of the weapons being used against us was an IMSI catcher. I had installed an application called AIMSICD onto my phone to track what cell sites my phone could see and connect to. There were patterns in the database that I believe suggest that there was an IMSI catcher on at least one of the aircraft that flew over the camps day in and day out as well as several other IMSI catchers at specific locations in the vicinity of the camps.

I am nearly certain that a short cell phone tower that was erected just to the south of the camp known as “1861 Camp”, “Treaty Camp”, or “North Camp” was there for the specific purpose of surveilling the people at that location because that camp was directly in the path of the pipeline construction, and immediately across the highway from a section of land that had already been dug up. That tower was only reachable if you were in the vicinity of the Treaty Camp, where only about 10 people were living but where many demonstrations were staged. The tower was completely invisible to the more populous camps a mile further south. Furthermore, that tower identified itself to some phones, including mine, as an AT&T tower, but other phones showed the tower belonged to Verizon. When I asked my contacts at the Standing Rock Telecom, a tribe-owned mobile phone company, they told me that tower was a legitimate Verizon tower. As time went on, there was more evidence that tower was there for surveillance purposes, but the clincher is that the tower was removed entirely by the time everything was over and the authorities had cleared out the camps.

Research into the capabilities of different models of IMSI catchers showed us that it was possible that, in addition to tracking our numbers and movements with the devices, they could also have captured voice, text and data transmissions and they could even install malware on phones through more than one method. It is also well known that IMSI catchers can drain a phone battery quickly by sending messages to the phone to disconnect from a tower over and over again. Each time the phone tries to reconnect to a tower, the battery usage spikes. But that doesn’t explain the incidents with the car batteries.

By Tim Yakaitis

We still don’t know what happened with the cars. When I first started talking publicly about the various cyber warfare incidents that happened at Standing Rock, the car batteries dying is the one incident that induced the most rolling of eyes and declarations of my professional incompetence. Obviously, the critics said, the car batteries died because of the cold. Everyone knows that the temperatures at the camps got below -20F (-29C) in December and January, but these car battery incidents happened starting in September! One incident in late October involved 5 cars in one parking area all having drained batteries at the same time. Another incident in November involved several cars and a couple of pick up trucks.

In April or May of 2017, after asking everyone I could think of what might have done that to the cars, an Iraq vet suggested that I go look up the word “Warlock”. He said that he thought that might be responsible for what we saw. What I found seems like an unlikely culprit since the Warlock series are just radio jammers of different sorts. However, there are other weapons that were created and tested in Iraq, such as the Blow Torch which is a high powered microwave emitter intended to fry the circuitry in an IED (Improvised Explosive Device). That’s probably not what they used, but the sheer number of devices that have been created and tested in battlefields by the US military in recent years is suggestive.

More than suggestive, actually. Over and over again Native Americans from different tribes across the US told me the same thing, “They’re testing things on us before they use them on the rest of the population.” A common historical understanding among the Native community is that the US government tests different methods of population control on the reservations before using the most effective ones on other Americans. As the tech team struggled to understand exactly what tools were being used against us online, on our phones, and in physical space, we couldn’t help but come to the same conclusion. Despite a collective knowledge that covered many areas of cyber security and digital offense, there were still many things we found that were completely new to us.

This Is (Low Intensity) War

“Low intensity conflict is a political-military confrontation between contending states or groups below conventional war and above the routine, peaceful competition among states. It frequently involves protracted struggles of competing principles and ideologies. Low-intensity conflict ranges from subversion to the use of the armed forces. It is waged by a combination of means, employing political, economic, informational, and military instruments. Low-intensity conflicts are often localized, generally in the Third World, but contain regional and global security implications”

The U.S. military doctrine of low intensity conflict has its roots in the counterinsurgency tactics developed during the Vietnam War. During the Reagan administration, in the 1980s, low intensity operations were used in a number of conflict areas throughout what was then called the Third World. The first International Conference on Low Intensity Conflict was held in 1986 at Fort McNair in Washington, DC where the methods of suppressing and subverting guerrilla fighters were discussed and codified.

In the context of guerrilla warfare, the dominant nation state actors will use various tactics to 1) turn the public against the insurgency, 2) break down morale within the guerrilla movement, 3) set individuals or groups within the movement against each other, and 4) sabotage the material support systems for both the insurgent groups and anyone who provides them assistance. Much of this effort comes in the form of psychological warfare which may include propaganda, infiltrators who plant rumors and conflicts, and consistent harassment of guerrillas and their supporters. Harassment includes but is not limited to checkpoints on roads, police stop and search actions against people who fit a certain visual description, aircraft constantly flying over the areas controlled by the guerrillas, the use of constant noise such as loud music or machines, and bright flood lights at night.

Once you know that the peaceful Water Protectors were considered terrorists by the government and Energy Transfer Partners, the company responsible for the Dakota Access Pipeline, it is not surprising to learn that all of these tactics were used against the movement.

Planes and helicopters flew overhead nearly 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, as long as weather permitted. At night, aircraft would often fly without lights so that you could hear them but not see them easily, despite the fact that this is illegal. Sometimes a helicopter would follow the car of a high profile Water Protector when they left the camps.

Multiple mobile police command centers were parked near the camps at any given time. There were often one or two of the giant trucks to the north of the main camp and as many as three to the south. On many occasions there would be a mobile command vehicle parked ten miles south of the camps at the Prairie Knights Hotel and Casino, where Water Protectors would go to take showers, spend a night indoors, charge phones, use the Internet, and meet with journalists.

When Water Protectors needed to purchase supplies, we traveled north to Bismarck, where we were recognized by the layered clothing we needed to survive in the camps and by our distinct campfire scent. Some stores, restaurants and hotels refused service to anyone they suspected was a Water Protector. Police would see a vehicle with out of state license plates and trail them for miles, often pulling the vehicle over on false pretenses. People of Native American descent, or anyone whose complexion was more brown then peach colored, was at greater risk of citation or arrest during a trip to the city.

For days before the raid of Treaty Camp on October 27, 2016 there were rumors about what was about to happen. We knew that National Guard troops were gathering at a site north of us, off of highway 1806 between Standing Rock and Bismarck. Rumors were that they might raid Oceti Sakowin, and we created safety plans for everyone that included running across the Cannonball River to the Sičangu and Sacred Stone camps. A few days before the raid, many people moved tents and tipis north to the Treaty Camp in hopes of holding the line away from the most populated camp. The tension was incredible, and elders warned us that we needed to stay calm if we wanted to have energy and our wits when the soldiers and police finally came. Those with experience made sure that as many people as possible understood that this tension and uncertainty was part of the psychological war.

The day of the Treaty Camp raid finally came, but one of the longer term attacks against us came after the mercenaries, law enforcement and National Guard pulled people out of a sweat lodge during a prayer ceremony, destroyed tipis, threw sacred items into giant piles, stole personal items, and arrested 142 people. The night after they took Treaty Camp away from us, they took away the stars. From that night onward, the ridge just north of Oceti Sakowin was lined with massive lights pointed towards the camp. They said it was for security, but they knew full well that it also obliterated the view of the night sky.

Inside the camps we had to be constantly aware of the risk of infiltrators. Some infiltrators encouraged people to use violent methods at actions so that the peaceful unity of the movement could be broken and images of “dangerous terrorists” could be displayed on TV, newspapers, and social media. There were people who came into camp just to spread rumors. The more confusion that could be spread, the harder it was for the community to stay united. And then there were people who intentionally created fights between different sub-camps or workgroups.

One infiltrator managed to break down the very good relationship that Tech Warrior Camp had with the camp of the Medic and Healer Council. After members of our team had set up a mini electric grid for the camp with the yurts and tipis where medical doctors and traditional healers from around the world cared for the Water Protector community, one infiltrator managed to create a fight between our two groups over the control and ownership of certain equipment. He told them that we had stolen some of their windmills (we had not), and told us that they were sending some of our equipment which had been stored in a utility yurt at their camp off to other Water Protector camps in Florida when we clearly still needed that equipment in North Dakota. I had to present receipts for every piece of equipment we had to representatives of the Medic And Healer Council, and still there was mistrust between our teams throughout January and February because of that incident.

Other infiltrators did physical damage to our camps. On one occasion, the Internet in the Dome was sabotaged when an infiltrator cut the wires from the network router to the deep cycle battery it ran off, and walked away with the battery. On another occasion, the entire solar system outside the Dome was was sabotaged before an infiltrator dressed as a utility worker cut the Ethernet cord leading to a small communications dish which he removed from the pole and took with him.

Only after the camps were closed did we have proof positive of some of the counterinsurgency tactics used against us. The Intercept published a series of articles along with leaked documents from TigerSwan, the private military contractor that provided “security” for the Dakota Access Pipeline, which showed that the mercenaries were working in close partnership with Morton County Sheriffs and the FBI. Those documents also showed that some of us where specifically targeted for surveillance both at camp and away from it, and that the mercenaries put special emphasis on creating divisions along racial lines at the camps to separate the Native community and their non-Native allies.

Some of the facts about what happened at Standing Rock won’t be known for decades. Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests for information on some of the police and military tactics have been denied for various reasons. The FOIA requests sent out to Morton County Sheriffs, North Dakota State Police, and the North Dakota National Guard asking for information about possible IMSI Catcher use, for instance, were not just denied but “rejected on grounds of national security”. Such a rejection will not be overcome until the classification of that information is changed at some future date. In the meantime, we have to take what lessons we can from Standing Rock so that we can resist capitalist destruction of the planet and colonialist theft of human and community rights everywhere.

Next Time...

We haven't even begun to talk about the community at the Water Protector camps at Standing Rock. I haven't begun to share the spiritual impact the place had on me and so many other people there. In my next installment of my Standing Rock Story, I'll tell you about what it was like to be a temporary immigrant on Lakota land for six months. See you in two weeks!

Eli Sterling

Eli Sterling is a crazy nomad woman who works on humanitarian technology, spending lots of time in low resource areas and disaster zones. They talk to plants, animals, gods and spirits. Some of them talk back.