Vinyl Paganism

Why Vinyl Rocks

When I was a child, we had a record player in our home. That's what we called it back then: not "turntable", but "record player". And the music was on "records", not "vinyl". Anyway, we actually had two record players. The family record player which played LPs (the "big records") and a small record player of my own that I played singles/45s (the "little records") on.

My father had given me a box of 45s from the 1950s. None of the music really appealed to me, though. But I did love an album called Switched-On Bach (1968), a collection of Bach pieces played on a synthesizer. I didn't know it at the time, but Switched-On Bach was actually really popular in the late 60s and early 70s. It reached number 10 on the US Billboard chart and sold over one million copies. It was partly responsible for the increased use of the synthesizer in popular music in the 70s. In 1979, one of the two artists, Wendy Carlos, came out as transgender, helping pave the way for generations of trans people after her. But I didn't know any of this at the time; I just knew I loved the album.

By that time, phonograph records had been around for about a century. I was too young to remember 8-tracks. When I became old enough to receive music as a gift, it was cassette tapes. (Tiffany was my “first”.) Since then, I've moved with everyone else through compact discs, mp3 players, and streamed music. But recently I've gotten back into records, or "vinyl" as we're now calling it.

Vinyl is "in" again. A lot of audiophiles claim that the sound of vinyl records is better than mp3 recordings. It has to do with something called "compression". When music gets transferred to a CD or an mp3 file (including streaming music), it gets compressed in order to save space. A song might contain 30 megabytes of data before compression and 3 megabytes afterwards. In the process, some of the sound gets lost. And also, the variations in the volume get leveled out. I have to admit, though, my ear is not so attuned (at least not yet) to appreciate the difference.[FN 1] But there’s other reasons why I am enjoying listing to records again. It has everything to do with why most people stopped using them in the first place: they're inconvenient.

To begin with, vinyl records are big. They're not as easy to store as cassette tapes or compact disks (or digital music obviously). You have to keep them free of dust. They're not exactly fragile, but they aren't as durable as cassettes or CDs. I learned the hard way that you have to have a decent turntable in order to enjoy them. (Forget about those cute Crosely record players. They skip terribly.) Even then, it probably isn’t a good idea to stomp around in the same room as you're playing a record. And it's not easy to pick and choose tracks. LPs are suited for listening to an entire album at once (or half of one before you have to flip the record over).

Initially, I bought a turntable and a few LPs out of a sense of nostalgia for my childhood. And I admit, at first, I found the experience annoying. I was so accustomed to the convenience of digital music that I gave up trying to enjoy it for a while. But it kept calling to me, and now it's grown on me. The same things that I found annoying initially are what appeals to me now.

1. Vinyl records are physical.

When you want to listen to records, you have to go to the place where you keep them. This is something that is often overlooked. Unlike digital music, which is transportable, vinyl music is placed. You probably keep them someplace special. You might even display them. And you’re going to listen to them in the place where you chose to set up your turntable, ideally a place suited to sitting and listening.

You’ll identify the album you want by the art on the front of the jacket. Appreciating the art of an album is part of the experience. You'll probably flip though multiple albums until you find the one you want. Each album jacket will be its own memory.

You'll pick the jacket up, handling it carefully, aware of its physicality. You'll probably flip it over and look at the back of the jacket too. Then you'll remove the record from the sleeve, holding it open-palmed by the edges so as to not put fingerprints on the surface. You’ll notice the feel of the vinyl itself, which is unique. You might blow on the record to remove dust. And you'll carefully place it on the turntable. If you have an automatic player, you'll just hit a button. But if not, you'll start the turntable and then carefully lay the needle on the track—not too far towards the edge or it will fall off and not too far in or you'll miss the beginning of the song.

While you listen to it, you may continue to look at the jacket. Maybe it's one of those jackets that opens up like book covers, or maybe it has an insert with more art, lyrics, or artist information. Or you might watch the record spinning, the arm rising and falling ever so slightly in response to a slight imbalance in the turntable. When you get to the end of one side, you'll have to get up to flip it over to listen to the other half. And when you're done, you have to store again it carefully.

You can get some of this experience with cassettes and CDs, but not as much as with vinyl. And it's completely lost with digital music.

2. Listening to vinyl encourages active listening.

You can listen to vinyl records in the background while you do something else, like have a dinner party or surf the internet on your phone, but you might as well just be listening to an mp3 in that case. With vinyl, you're more likely to make listening your sole activity (other than looking at the album jacket maybe). Because of the effort that goes into it, you'll be more likely to give it your full attention.

3. Vinyl albums have their own internal logic.

It's not easy to pick out and play individual songs on an LP. Trying to land the needle right at the beginning of the track requires some skill. So you'll be less likely to listen piecemeal and will appreciate the album as a whole.

Listening to vinyl encourages long listens. Vinyl LPs are albums. We've largely lost the sense of albums as albums. An album isn't just a random collection of singles. It is a whole which is more than the sum of its parts. It represents a specific time in that artist’s career. Artists will have selected the tracks to play in a certain order for a reason of their own. We lose that sense of wholeness when we listen to digital playlists, which skip between albums, artists, and even musical genres.

4. The sound of vinyl is imperfect.

I hear the audiophiles gasping. Yes, I know that vinyl is supposed to have a more complete and robust sound than CDs or digital music. But I'm not talking about the purity of the recording. I'm talking about the distinctive (and nostalgic) crackle sound of a needle on a record. If you're only used to digital music, it may be distracting at first. But it's a reminder of the tangibility of the medium. Its physicality can remind you of your own physicality. It makes listening more embodied.

The Growth of Internet Paganism

Now, what does any of this have to do with paganism? I’m going to argue here that the experience of paganism is increasingly becoming more like streaming music than listening to vinyl records, and that something vital is lost as a result.

Helen Berger, who is perhaps the most well-known sociologist of contemporary Paganism, recently published an article entitled, ”As witchcraft becomes a multibillion-dollar business, practitioners’ connection to the natural world is changing,” in which she briefly describes how both the acquisition of knowledge about and the practice of paganism has changed over the years. The way we learn about paganism has gone from having a direct encounter with the wild more-than-human world, to learning from a teacher who has been initiated into an esoteric tradition, to reading a book we found in a library or bought in an occult shop, to watching teen witches on TV, buying a book which is delivered to your door by Amazon, watching 3-minute Witchtok videos, and buying a pink plastic witch kit from Sephora.

Of course, there's still people who learn about paganism from direct experience or from in-person teachers. But more and more people are coming to it in other ways. The way one first encounters paganism isn't going to determine how they will learn about it or how they will ultimately engage with it. None of these entry points are mutually exclusive. A Sephora witch kit could be a gateway to a direct encounter with the wild world—though the opportunities for that are rapidly disappearing as a result of the same economic system which produces the Sephora witch kit.

In any case, as Berger observes, it’s not just how we learn about paganism that is changing. The way many are practicing paganism is changing as well. Berger doesn't offer any statistics to support her impressions, but I suspect that she is right. Almost every other aspect of our lives is becoming increasingly virtual. Ernest Cassirer’s observation in 1956 about how our experience is increasingly mediated is even more true today:

"No longer can humankind confront reality immediately; they cannot see it, as it were, face to face. Physical reality seems to recede in proportion as humankind's symbolic activity advances. Instead of dealing with the things themselves humans are in a sense conversing with themselves. They have so enveloped themselves in linguistic forms, in artistic images, in mythical symbols or religious rites that they cannot see or know anything except by the interposition of an artificial medium.”

— Ernst Cassirer, An Essay on Man (1956) [quote edited for inclusive language]

This must be even more true today, especially since COVID. And pagan spirituality is no exception. Writing almost a decade ago, media studies scholar and witch, Peg Aloi, observed:

"The development of various forms of social media and their increasing sophistication ... has seemingly glamoured us into thinking that this movement is one which can be lived and expressed almost entirely in cyberspace. There are now hundreds of thousands of people who identify as 'pagan' or 'Wiccan' or 'Druid' or what have you who have never conducted a ritual out of doors, who have never attended a festival at a campground, who have never planted a garden in honor of the Eternal Return of the Earth Mother in spring. Do they discuss the gods and their ritual practices and spells and theology? Sure! But do they get their hands dirty, in actual dirt? Not so much.”

— Peg Aloi, “Has Pagan Environmentalism Failed? Yes, Yes, A Resounding Yes.” (July 25, 2014)

In Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World (2020), Tara Isabella Burton explores the new social movements which are coming to function as religions in a post-Christian America. She includes among these: various fandoms, wellness culture, polyamory and kink communities, social justice movements (especial social media call-out culture), techno-utopianism, and what Burton calls "reactionary atavism" (which includes everything from Jordan Peterson to incels). Collectively, Burton calls these movements "intuitionalism" (distinguished from institutionalism) or the "remixed". And among this hodgepodge, Burton also includes a chapter on contemporary witchcraft, entitled "The Magical Resistance". Burton explains that there are three factors driving this transformation: demographics, capitalism, and the internet. Each one of these deserves an essay of its own. But for present purposes, I want to focus on the last one: the internet.

Now, I want to say here, I am no Luddite—at least not in the pejorative sense of the word (though in the historical sense, I have many sympathies). I have a facility for computers, and the internet has felt like a godsend to me. As for many others, the internet satisfies both my appetite for information and new ideas, while also allowing me to direct the path of my intellectual explorations (at least to the extent that the algorithms allow). But I've come to question whether virtual spirituality is a contradiction in terms.

The Medium is the Message

In 1964, communications theorist, Marshall McLuhan, coined the phrase, "The medium is the message." By this, he meant that changes in the technology of communication (the medium) necessarily change the content of communication (the message). Or, to put it another way, the content of our discourse changes to make itself more amenable to the new technology. Building on McLuhan, Neil Postman, author of Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985), explains:

"Each medium, like language itself, makes possible a unique mode of discourse by providing a new orientation for thought, for expression, for sensibility ... The forms of our media, including the symbols though which they permit conversation ... are rather like metaphors, working by unobtrusive but powerful implication to enforce their special definition of reality. Whether we are experiencing the world through the lens of speech or the printed word or the television camera, our media metaphors classify the world for us, sequence it, frame it, enlarge it, reduce it, color it, argue a case for what the world is like.”

— Neil Postman, Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)

As communication has shifted from the oral to the written, to the visual (TV), and to the digital (internet), there have been corresponding shifts in our politics, education, and even our religions.

The technological transition that concerned McLuhan and Postman was from print to television (both were writing before the internet). Many others, going all the way back to Plato, have commented on the importance of the shift from oral to literate culture. David Abram in Spell of the Sensuous (2012) and Leonard Shain in The Alphabet Versus the Goddess (1998) have both written about the importance of the shift from logographic to alphabetic script.

And it’s not just informational technologies that mediate our experience. In his essay, “Dark Ecology”(2012), Paul Kingsnorth[FN 2] contrasts the use of the scythe to a mechanical brushcutter for how we interact with the land:

“Using a scythe properly is a meditation: your body in tune with the tool, your tool in tune with the land. You concentrate without thinking, you follow the lay of the ground with the face of your blade, you are aware of the keenness of its edge, you can hear the birds, see things moving through the grass ahead of you. Everything is connected to everything else, and if it isn’t, it doesn’t work. …

“A brushcutter is essentially a mechanical scythe. It is a great heavy piece of machinery that needs to be operated with both hands and requires its user to dress up like Darth Vader in order to swing it through the grass. It roars like a motorbike, belches out fumes, and requires a regular diet of fossil fuels. It hacks through the grass instead of slicing it cleanly like a scythe blade. It is more cumbersome, more dangerous, no faster, and far less pleasant to use than the tool it replaced. And yet you see it used everywhere: on motorway verges, in parks, even, for heaven’s sake, in nature reserves. It’s a horrible, clumsy, ugly, noisy, inefficient thing. So why do people use it, and why do they still laugh at the scythe?

“To ask that question in those terms is to misunderstand what is going on. Brushcutters are not used instead of scythes because they are better; they are used because their use is conditioned by our attitudes toward technology. Performance is not really the point, and neither is efficiency. Religion is the point: the religion of complexity.”

—Paul Kingsnorth, “Dark Ecology” (2012)

Ivan Illich referred to this as the “deep structure” of tools. Yes, it’s true that both the scythe and the brushcutter are technologies for cutting down vegetation. Both mediate our experience of the landscape, but each mediates our experience differently. Something is gained and something is lost with each.

A good example of this is turn-by-turn GPS. My wife tried for years to get my kids to learn how to read a roadmap and they resisted her. In retrospect, I was less supportive than I should have been. I thought, when are they even going to be without a phone? My attitude changed when my wife returned from a cross-country trip where she had gotten detoured off the interstate in Wyoming and found herself on a small road in the countryside without an internet connection.

It was night and the sky was clear. By locating Orion’s Belt and then the North Star, my wife oriented herself and eventually found her way back to the interstate. I was impressed by her ingenuity. I imagined how lost my children would have been under those circumstances. Her experience made me realize, not just our dependence on technology, but how our technologies, like turn-by-turn GPS, disconnect us from our sense of place in the world.[FN 3]

I think of my wife’s experience when I read Emerson’s words written almost two centuries ago:

“Society never advances. It recedes as fast on one side as it gains on the other. ... For every thing that is given, something is taken. Society acquires new arts, and loses old instincts.

"The civilized man has built a coach, but has lost the use of his feet. … He has a fine Geneva watch, but he fails of the skill to tell the hour by the sun. A Greenwich nautical almanac he has, and so being sure of the information when he wants it, the man in the street does not know a star in the sky. The solstice he does not observe; the equinox he knows as little; and the whole bright calendar of the year is without a dial in his mind. His note-books impair his memory; his libraries overload his wit; the insurance-office increases the number of accidents; and it may be a question whether machinery does not encumber; whether we have not lost by refinement some energy, by a Christianity entrenched in establishments and forms, some vigor of wild virtue.”

— Emerson, “Self-Reliance” (1841)

And what is true of the brushcutter and the scythe, as well as GPS and the roadmap, is also true of the internet and the technologies it replaces. One is what Ivan Illich calls a “tool for conviviality”—a technology that enables us (or at least doesn’t interfere with) our being together with other beings—and the other is not. For example, in the 1973 book of the same name, Illich described how cars (and the concomitant car culture) actually “create distance” between people. And the same could certainly be said of the internet.

1. Internet “spirituality” is disembodied and dis-placed.

Like listening to streamed music, virtual spirituality is disembodied and dis-located. As I wrote in my essay last month, "Re-Placing Ourselves”, it’s true that the internet allows us to “connect” with people with whom we might never have interacted, but it has also accelerated the withdrawal from face-to-face communities of place. Because the “connections” which are created online usually remain in the virtual realm, they remain disembodied and dis-located. Cyberspace is the most non-place of all non-places. As virtual communities replace in-the-flesh communities, we lose the embodied connections to real places and people. And this applies to our spiritual communities as well.

2. Internet “spirituality” can be passively consumed.

When I first encountered the internet in the mid-1990s, I felt like the world had been opened up to me for exploration. Finding information online back then still took time and work. The algorithms that determined search engine results were not so developed, and social media did not yet exist. Over time, though, our way of interacting with the internet has changed. Now, we consume information largely through various social media feeds. And we are not so much exploring as being spoon-fed what profit-driven algorithms dictate.

Music streaming services not only allow us to create playlists, but also curate playlists for us based on our past listening history and the “invisible hand” of marketing techs. The same goes for how we consume spirituality. Capitalism doesn’t free us to consume what we want; it tells us what we should be consuming—which is usually a vapid, whitewashed, monoculture facsimile of practices which once provided deep meaning and real fulfillment.

3. Internet “spirituality” is on demand.

“As we increasingly consume our religious information the way we do the rest of our media—curated, like our Facebook feeds—so, too, does our religious ‘feed’ become increasingly bespoke. … The Internet has also made us hungrier for individualization, for products, information, and groups that reflect more exactly our personal sense of self."

— Tara Isabella Burton, Strange Rites: New Religions for a Godless World (2020)

What’s wrong with that? you might ask. Why shouldn’t our spiritualities be tailor-made for each of us? But as our spiritualities become more individualized, more “bespoke” (to use Burton’s word), we lose something crucial. These "plug-and-play spiritual practices are decontextualized and often appropriated from oppressed minority cultures, so we lose the depth of meaning and connection to the communities that created them together over centuries or millennia.

We also lose the experience of being challenged by an “other”. Our “designer gods” turn out to be little more than reflections of our own egos. The internet, writes Burton, “has also encouraged us, as consumers with a cornucopia of options, to seek out, even demand, a creative role in designing our own experiences, including spiritual ones.” She goes on, “the Internet provides highly specialized alternative communities, allowing people to find friends or partners who aren’t merely like-minded, but almost identically minded. It disincentivizes compromise and conformity…”

As an example, Burton quotes one of the founders of the Ritual Design Lab, which designs custom, non-theistic rituals for callers:

“The new generation want[s] bite-sized spirituality instead of a whole menu of courses. Design thinking can offer this because the whole premise of design is human-centeredness. It can help people shape their spirituality based on their needs. Institutionalized religions somehow forget that at the center of any religion should be the [individual] person.”

— Kursat Ozenc (Ritual Design Lab), quoted by Tara Isabella Burton

I recently attended the Parliament of the World’s Religions, where I heard one presenter, a Pagan high priestess entrenched in wellness culture, who represented this attitude exquisitely. Without any qualification or reservation, she explained how her spirituality is expressed by a sign which she purchased (of course) which said, “Me. Me. Me.”[FN 4]

While initially gratifying, these human-centric and self-centric “bespoke” spiritualities ultimately leave us with the empty feeling of staring at ourselves in the mirror. Absent is the transcendence of self, the connection to something bigger than ourselves, the ecstasy—a word which etymologically means “to stand outside oneself”—of communion with another being. While there is an important role for self-assertion in the development of spirituality, when we remain there, when individuation is not balanced by community or by connection to the self-transcendent, then it is a recipe for an immature spirituality.

4. Internet “spirituality” creates an expectation of perfection.

The corollary to all of this is a dissatisfaction with anything that does not immediately live up to our expectations, an impatience with “imperfection”. We come to expect an ideal, which is disconnected from the messiness of embodied life, of living in a specific place at a specific time and sharing that space and time with real people with their own histories and preferences.

Vinyl Paganism

I’m not suggesting we disconnect from the internet entirely (though the practice of a technology Sabbath has much to recommend it). We’re not going back to an oral culture or even an analog one very soon (though we probably will eventually). What I am suggesting is a conscious downshifting of technology in some areas of our lives—especially in our spirituality, in order to recover some of what has been lost. Much like a Sephora witch kit, the internet can be a gateway to that experience we call “paganism”, but without the encounter with the wild more-than-human world, it does not deserve the name.

I am suggesting that, at least some of the time, we should intentionally choose technologies that allow us to slow down, pay attention, be present in place and in our bodies, and let the more-than-human world speak to us in its own way. And I’m calling this “vinyl paganism” because of the ways it resembles the practice of listening to vinyl in an age of digital music.

1. Vinyl paganism is embodied and placed.

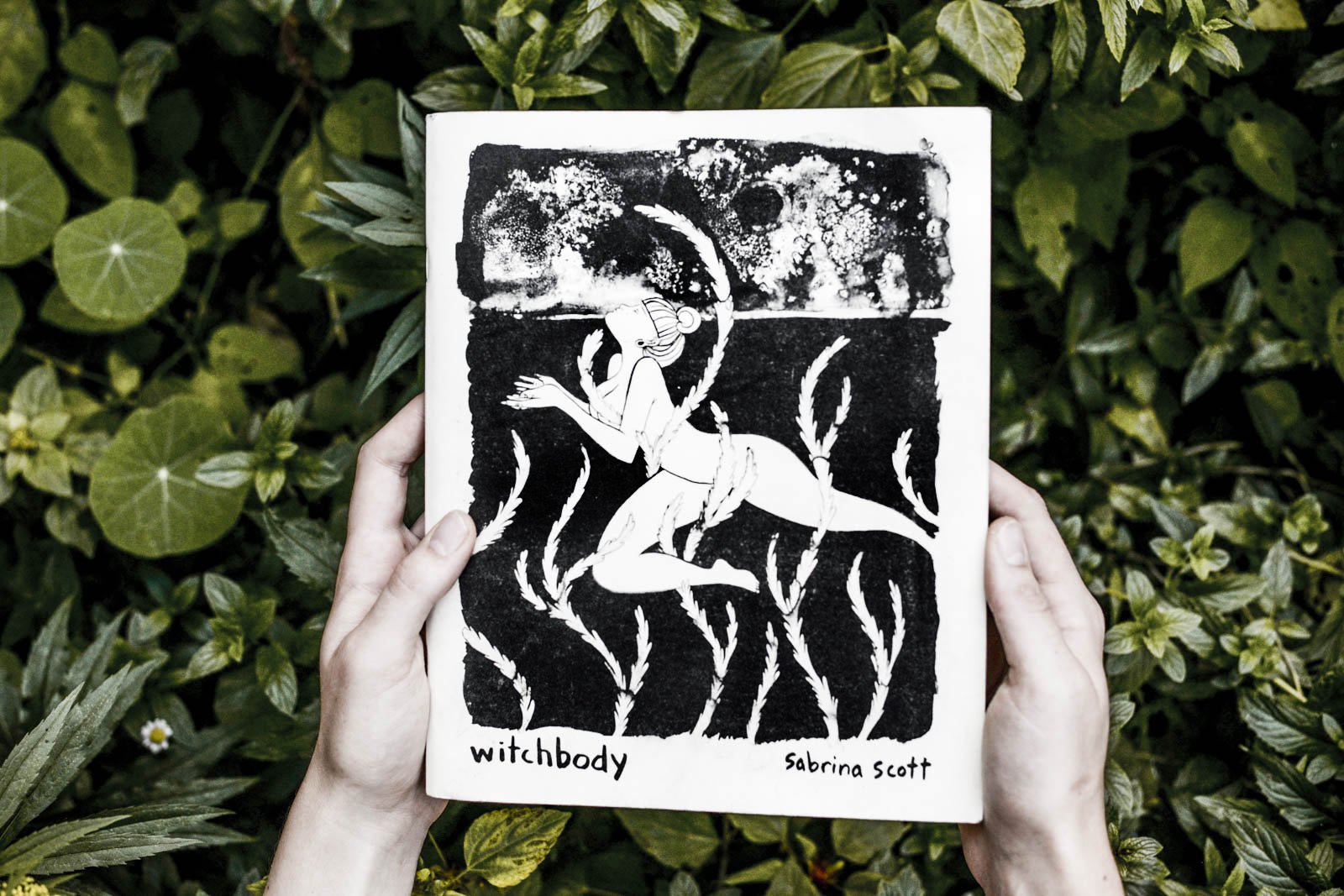

To illustrate what I mean by “vinyl paganism”, I will draw on Sabrina Scott’s 2019 book, Witchbody. Though Scott doesn’t mention vinyl records at all, it’s a great example of what I mean by the term. To begin with, Scott’s book is beautifully illustrated with flowing images of bodies: the author’s body, animal bodies, living and dead, the body of the land, both beautiful and broken.

Scott’s witchcraft (like my paganism)[FN 5] is embodied. She writes,

"Witchcraft knowledge is body knowledge.”

“Witchcraft is a body pedagogy that makes sense of the idea that other bodies may feel us, too.”

“Witchcraft feels the self touching others …”

"To be a witch in the Western context is to privilege body as a site of finding out about other beings. To be a witch is to know that we are the environments of others.”

"If there is an essence of witchcraft it is relationship with other bodies with whom one shares space ..."

Of course, embodiment implies being placed. Scott writes about the importance of “simply dwelling where we are”.

Like listening to vinyl records, vinyl paganism is a practice of downshifting our use of technologies so as to recover some of what we have lost, like our experience of being embodied and dwelling in a place. In contrast to internet spirituality, vinyl paganism is both embodied and placed. It simply cannot be practiced with the mind alone—and thus it cannot be practiced virtually. You have to get your hands dirty, both figuratively and literally. And you have to use your whole body, all of your senses (even some that you may not have realized you had before). “To be a witch is to become open to learning differently, to read books as well as sensation, smell, saliva, soil, miaows, dreams,” writes Scott.

2. Vinyl paganism requires active participation.

Unlike internet spirituality, which can be consumed passively, vinyl paganism requires our active participation. In fact, it is in that participation that the experience we call paganism happens. Participation implies relationship, and magic, writes Scott, “is a method of delving deeply into relationship.” She invites us to embrace our “entanglement”. My favorite quote from Scott’s Witchbody is this one:

"Thinking with Donna Haraway, I position magic as a 'contact zone,' a space where bodies meet and notice their meeting. What is significant about magical practice is not that it is the only space where bodies are entangled. It certainly is not. Magic is unique because it draws attention to these relationships. In magic, trans-species entanglement is noticed with more frequency and intensity because the agencies of other-than-human beings are intentionally enlisted in collaborative efforts to do things, to effect change, to instigate material difference. Within a magical framework, entities don't exist solely to be exploited by humans.”[FN 6]

— Sabrina Scott, Witchbody (2019)

In contrast to the Abrahamic religions, which tell a story of essential estrangement, the quintessential pagan experience is not one of separation, but of relationship or participation— relationship to our bodies and to the land we inhabit, participation with one another and to the other-than-human inhabitants of the land. Vinyl paganism is always, necessarily practiced through these relationships. Like listening to vinyl records, vinyl paganism demands more of us than passive consumption. It requires that we embrace our entanglement with others.

3. Vinyl paganism requires us to let the wild world speak in its own terms.

In one place, Scott writes of “plants recruiting humans to enact magic”. In this way, she reverses the human-centric narrative which always sees humans as the actors and the more-than-human world as an object to be acted upon. “We can disrupt the ubiquitous, anthropomorphic storying of power,” writes Scott. “Between humans and other-than-humans, magic shifts openness to rethinking who speaks and who listens, who performs and who watches, and who acts and who is a backdrop for action.”

The wild world has its own intelligences, its own intentions, its own wills. In the introduction to the website for the Alliance for Wild Ethics (founded by ecologist David Abram), “wildness” is defined as:

"the earthy, untamed, undomesticated state of things—open-ended, improvisational, moving according to its own boisterous logic. That which is wild is not really out of control; it is simply out of our control. Wildness is not a state of disorder, but a condition whose order is not imposed from outside. Wild land follows its own order, its own Tao, its own inherent way in the world.”[FN 7]

— Alliance for Wild Ethics

The technological paradigm cuts us off from the intelligences and wills of the more-than-human world and makes everything into a tool to be used or a commodity to be sold by humans. As Theodore Roszak explained in The Making of a Counterculture (1969), “Nothing we come upon in the world can any longer speak to us in its own rights … [They] have been deprived of the voice with which they once declared their mystery to humankind.” Roszak contrasts this with an alternative mode of consciousness which is related to indigenous magic and to Martin Buber’s pansacramentalism, one which addresses the world, not as an “it”, but as a “thou”.

The word that Tara Burton uses to describe the curated and individualized spiritualities offered to us by the internet and capitalism is “bespoke”. As in: "More and more Americans—and particularly more and more millennials—envision themselves as creators of their own bespoke religions, mixing and matching spiritual and aesthetic and experiential and philosophical traditions." The word "bespoke" originated in the 16th century and referred to custom-made or made-to-order goods. It literally meant "to speak before", as in to say what you want before you see what is available.

In contrast to the bespoke-ness of internet spiritualities, vinyl paganism requires that we let the wild world speak to us in its own terms. Like listening to an entire music album in order to experience the wholeness of an artist’s intent, vinyl paganism invites us to let someone other than ourselves direct the course of our experience. Less like listening to a curated playlist and more like attending a live concert.

Scott writes, “Witchcraft is the act of saying hello. Speaking back to ones who speak to us.” This requires, of course, that we are listening to those who are speaking. “In magic,” she writes, “we listen and the expressions of other-than-human beings become valued communications, stories, confessions—incomplete, but heard. Seen. Wondered about.” “Magic,” says Scott succinctly, “helps us listen better.” Like listening to vinyl records, vinyl paganism isn’t “on demand”. It requires us to let others speak for themselves and it requires us to listen.

4. Vinyl paganism deconstructs purity spirituality.

The concepts of purity and perfection have haunted the Western mind since Plato and the subsequent domination of the Abrahamic religions. Paganism is arguably the antithesis of Platonism, a deconstruction of the very concepts of purity and perfection, the ideal and the disembodied. Paganism is messy. How could an embodied practice of encountering other wild bodies be otherwise?[FN 8]

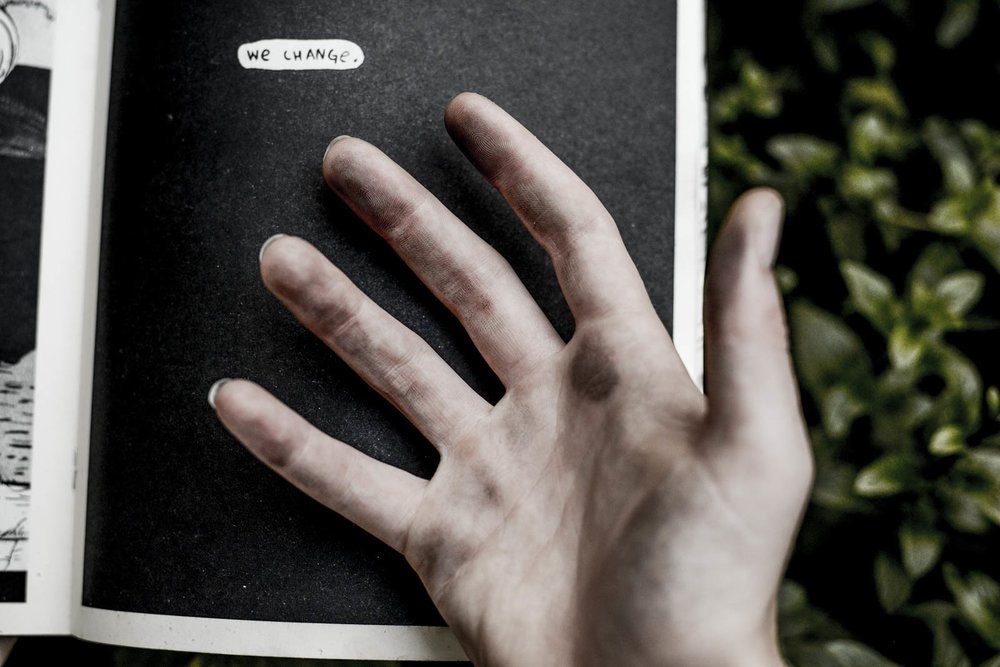

Scott’s Witchbody is about as good an illustration of this as any book could be. The first thing you notice when you open it is the script. (Well, ok, the first thing you probably will notice is the beautiful flowing woodcut-style artwork. But the second thing you will notice is the script.) It looks like someone’s journal. The margins aren’t straight. The script isn’t uniform. Some of the words and letters are written with a heavier hand than others. Some are even a little hard to read. There are mistakes, which are actually scratched out.

Scott makes the reason for this clear in the introduction: “[This] is a book that becomes richer when read, ripped, touched. As you read, the ink may smudge, smear. It may leave marks on your fingers; so touched, you may touch the book and leave your mark, visible, undeniable.” To write in such a beautiful book rubbed against something deep inside me. But I took Scott’s advice and made a practice of underlining phrases, and even whole passages, circling words, and putting stars next to especially important ideas. (As a compromise with my vestigial puritanicalism, I used a pencil.)

Scott carries this rejection of purity culture into her theology[FN 9]: “We must account for the fallen, the dead, the changed, the unnoticed, the ugly—and embrace them …” She goes on:

"We can't keep only seeking the most pristine spirits, the most pristine material bodies. Nothing has ever been 'pure.' We shouldn't only pay attention to manicured candy-coated lawns but also waste, garbage, forest, marina, skyscraper, landfill, prosthesis [and, I would add, vinyl records]. Everything in between.”

— Sabrina Scott, Witchbody (2019)

***

Listening to vinyl records has become for me both a spiritual practice in its own right and a reminder of what I want my paganism to be: embodied and placed, demanding of my active participation in the more-than-human world, and decentering my ego specifically and humankind generally. Like listening to vinyl records, vinyl paganism requires me to slow down, be present, really listen, give in to an experience that is co-created in relationship with other beings, and embrace the messiness of the wild world.

My Favorite Vinyl LPs

I excluded from this list any “greatest hits” albums. You can share your favorite albums in the comments. As you can see, I have a weakness for sultry feminine voices. (Please, don't yuck my yum!)

Adele, 21 (2011)

Bee Gees, Saturday Night Fever soundtrack (1977)

James Blunt, Back to Bedlam (2004)

Evanescence, Fallen (2003)

Fleetwood Mac, Rumours (1977)

Florence & The Machine, Ceremonials (2011)

Jewel, Pieces of You (1995)

Natalie Merchant, Tigerlily (1995)

Sarah McLachlin, Surfacing (1997)

Notes

Apparently, there’s also some debate about the loss of quality caused by Bluetooth speakers/headphones compared to wired ones—something I have yet to experiment with.

Over a period of a few years, Paul Kingsnorth’s political orientation has shifted from Green anarchism to proto-fascism. While it is impossible to draw a bright line marking when this occurred, I cannot unequivocally endorse Kingsnorth’s writing after the spring of 2020. COVID and his conversion to Orthodox Christianity appear to have accelerated his slide to the right. See here for more on this.

In my job as an attorney frequently handling car accident cases, I often ask people to tell me what direction they were traveling when the accident occurred. At least 90% are incapable of doing so accurately, and almost that many don’t even try, saying dismissively, “I’m not good with directions.” For this reason, even one of the most basic of pagan ritual practices, invoking the cardinal directions, can be an important tool for grounding ourselves in a place. As Julie Schotten and Richard Rogers explain, pagan ritual can work to ”overcome the trained incapacities of modern literates [I love that phrase!], incapacities that are central to the objectification, exploitation, and destruction of the natural world.”

To my mind, the unapologetic self-centeredness of this person’s spirituality causes me to question her adoption of the title “priestess”, a term which (at least as I understand it) implies the existence of a community. Tara Burton frames the problem well in her conclusion: “Internet creative culture and consumer capitalism have rendered us all simultaneously parishioner, high priest, and deity."; and in her introduction: “… when we are all our own high priests, who is willing to kneel?”

Though Scott is describing witchcraft specifically, I think her description applies more broadly to paganism generally, at least as I understand it. Though I know there are men who call themselves “witches”, for me, the term is inextricably bound up with the unique form of oppression experienced by women and female bodies under patriarchy, and so I prefer the term “pagan” or “animist”.

Elsewhere, Scott writes, “Magic instigated for the sake of getting results is quickly eclipsed by inescapably important dialogue, care, and strengthening of relationships necessary to sustain the practice.” For this non-instrumental conception of magic, Scott acknowledges her indebtedness to Julie Schotten and Richard Rogers, who write:

“magick is not something people do, separate from nature, merely in order to influence something ‘out there’—be it human or other-than-human. Instead, magick represents the interaction of the human and other-than-human, of culture and nature, in a potentially nonhierarchical form. Magick is an effort to enact communicative relations between humans and the natural world, relationships that breakdown the dominance of abstraction as well as the separation of humans from the rest of nature.”

“Magic as an Alternate Symbolic: Enacting Transhuman Dialogs”, Environmental Communication 3(3) (2011). This understanding of magic as relationship jibes with the non-instrumental theory of magic I have promoted elsewhere.

Paul Kingsnorth explains that "The Amazon is not important because it is 'untouched'; it's important because it is wild, in the sense that it is self-willed. It is lived in and from and by humans, but it is not created or controlled by them. It teems with a great, shifting, complex diversity of both human and non-human life, and no species dominates the mix." (“Dark Ecology")

Schotten and Rogers’ observe that pagan ritual or magical practice is a sensory/sensual/erotic experience in which “other-than-human entities are embraced as full co-participants”. This, they write, has the effect of recovering “the concrete from the dominance of the abstract, eros from the dominance of rationality, the material from the dominance of the ideational, and the natural from the dominance of culture.” They go on to say that “the erotic and concrete/material foundations of magickal practice ultimately lead to a rejection of notions of purity that abound in contemporary environmental discourse and practice [and elsewhere]”. Julie Schotten and Richard Rogers, “Magic as an Alternate Symbolic: Enacting Transhuman Dialogs”, Environmental Communication 3(3) (2011).

This recalls the work of Trebbe Johnson, who invites us, in Radical Joy for Hard Times (2018), to dwell in the broken places of our world, rather than hiding them away from our sight. (More on that in a future essay.)

JOHN HALSTEAD

John Halstead is the author of Another End of the World is Possible, in which he explores what it would really mean for our relationship with the natural world if we were to admit that we are doomed. John is a native of the southern Laurentian bioregion and lives in Northwest Indiana, near Chicago. He is a co-founder of 350 Indiana-Calumet, which worked to organize resistance to the fossil fuel industry in the Region. John was the principal facilitator of “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment.” He strives to live up to the challenge posed by the Statement through his writing, activism, and spirituality. John has written for numerous online platforms, including Patheos, Huffington Post, and Gods & Radicals. He is Editor-at-Large of NaturalisticPaganism.com. John also edited the anthology, Godless Paganism: Voices of Non-Theistic Pagans and authored Neo-Paganism: Historical Inspiration & Contemporary Creativity. He is also a Shaper of the Earthseed community, more about which can be found at GodisChange.org.