Review: The Two Antichrists, by Peter Grey

Originally published at our supporters’ journal, Another World

Also available as a downloadable PDF here.

A reading by the reviewer of the first section of The Two Antichrists is also available at the end of this review.

Isaac Newton, the inventor of a general theory of mechanics, gravity, and the refraction and expandability of light (which made the laser possible), spent the vast majority of his time searching for the Philosopher's stone, categorizing angels, and interpreting theological prophecies. Roger Bacon, whose advocacy for empiricism marks him as the founder of the modern “scientific method,” wrote extensively on astrology and natural magic.

John Dee, Queen Elizabeth’s trusted political advisor, who formulated a vision of imperial colonies which she in turn implemented, is better known for his occult studies in sorcery, alchemy, and Hermetic magic. Jean Bodin, the author of Les Six livres de la République—the founding text which defined the modern Nation-State—devoted much of his intellectual work to plumbing the diabolic pacts which enabled witches and sorcerers to cast spells.

Carl Schmitt, the German jurist whose theory of sovereignty forms the basis for government COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns and other national emergency measures in “democratic” nations, was also a Nazi who believed the expulsion of Jews from Germanic lands would trigger an esoteric prophecy bringing back Christ. Countless anarchist theorists in the 1800’s were also members of Masonic lodges and other secret occult societies, whichhelped them spread their ideas. And Jack Parsons, the co-founder of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, whose engineering and chemistry work led to the rockets which launch the satellites which now orbit our earth and define our global communication, was also an occultist who attempted to summon Babalon to earth.

To mention the occult and esoteric interests of such men is not to reference their shared hobbies as a matter of curiosity, but rather to point to something we prefer to ignore about our secular, scientific age. The core conceit of our “age of reason” is that we are no longer superstitious, that men of science and philosophy have shaped the world in which we live as places of pure rationality, cleansed of a primitive past in which learning meant also knowledge of magic.

However, once we shrug off the myth of any kind of division between science and the esoteric, we can instead see in the contours of our current political, economic, and material nightmares the glint of magical design. John Dee, for example, dreamt the British Empire into existence, convincing the Queen he tutored to organize the exploitation of foreign lands into permanent colonies. From the mind of a magician, then, came the conquering of the Americas, the implementation of the slave trade to work British plantations, the slaughtering of indigenous peoples to “clear” the land, and ultimately the birth of the world’s most violent imperialist power: The United States.

“We Will Not Be On That Rocketship”

Just beyond the edge of capital’s silhouette, there in the subtle penumbra of the political struggles of race and colonization, in the legacy of abductions of children into Canadian residential schools, Australian and American displacements of natives and aboriginals, and ultimately the catastrophic changes to the climate of the earth itself was a whisper from a sorcerer who claimed hear whispers from beyond the stars.

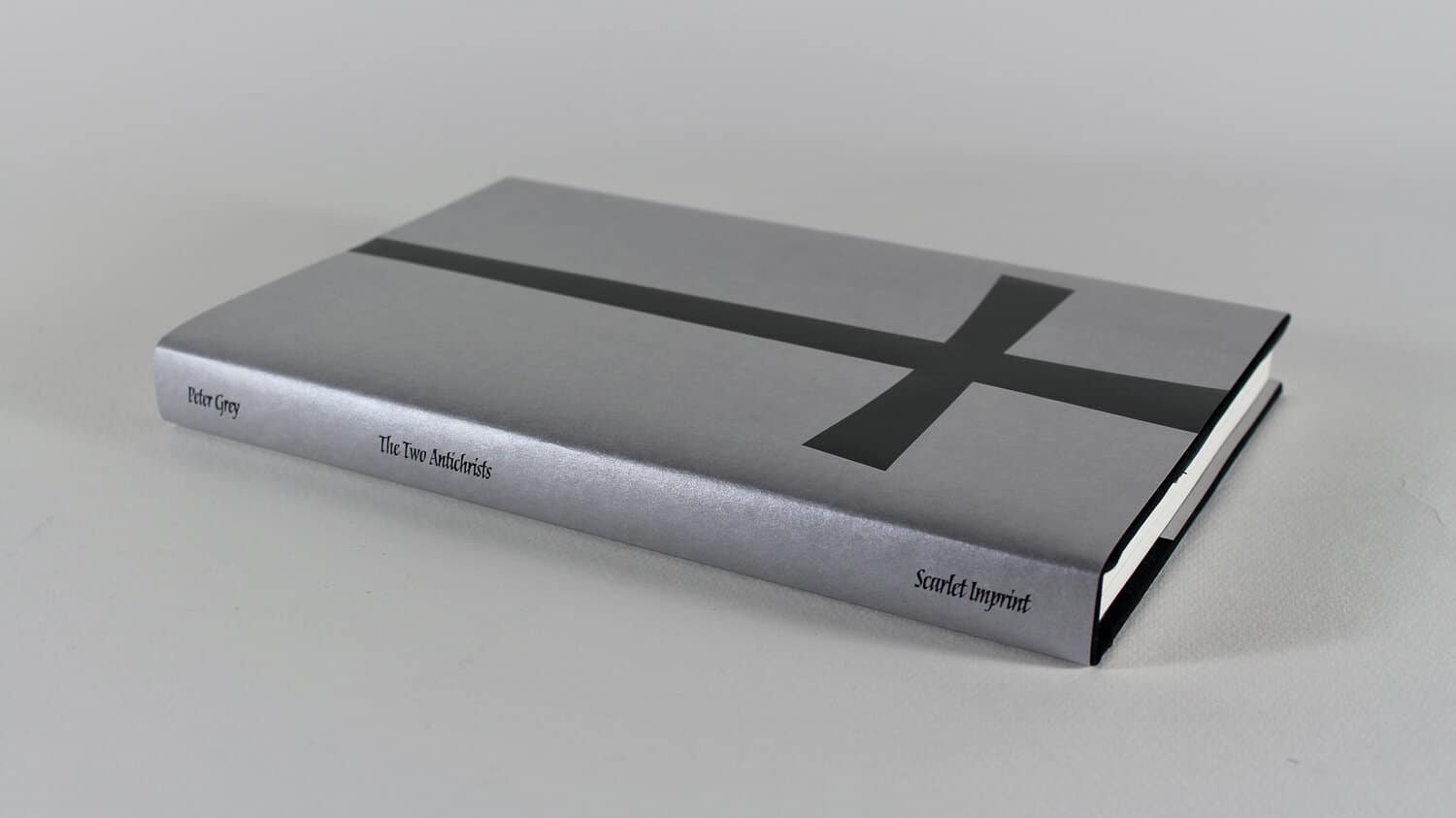

Whether we are happy with this or not, the conditions of humanity now and the future of humanity itself has been shaped by occult forces and the wild dreams of esotericists just as much as by politicians and historic forces. This is one of the premises of Peter Grey’s most recent work, The Two Antichrists, a startling book that I found initially difficult to reconcile with the rest of Grey’s work (and Scarlet Imprint’s corpus).

The reason for this initial difficulty was in Grey’s opening of the book, “The View From The Abyss,” which serves as both introduction to the rest of the work but also as a kind of manifesto for a reclamation of the dream of interstellar travel. Addressing first the current state of our dying planet and the failure of all efforts at resistance against the authoritarian shift of governments, Grey dismisses what he sees as immature—or more precisely, uninformed—fantasies that escape into nature would have any effect on the current trajectory of global industrial civilization.

There is a radical tension between taking our place in the stars and an ecological movement making a final stand as a result of that industrial process. Increasingly; we will be asked: are you for ecology, of for Mars? The question bluntly assumes we must be either accelerationists or anarcho-primitivists. I am neither.

For Grey, the problem is that what has already been set in motion cannot—even by the most extreme acts—be stopped or derailed, as the “aperture” is already too narrow for such actions. The best any ecological movement whose goal is a return to pre-industrial levels of pollution can hope for is mass human death, while as he notes the technological solutions clung to by both capitalists and left-liberals are “the logic of Zeno, where through incremental savings we never reach the point of destruction. It is a noble metaphysical lie for those who want to live with meaning, and an ignoble lie for those who are mandated to profit from an acceleration industrialism.”

Letting go such delusional fantasies means instead looking clearly at the real situation of the earth and its trajectory. Humans will go off-world, but not all humans. “We will not be on that rocketship,” he reminds us, instead left staring at the wreckage of progress from our earth-bound slums:

Above us will hang a ravaged lunar surface whose dreaming seas are trawled for the propellants that will take us to Mars. Consider this when you stand naked beneath our virus-clarified sky and gaze at the pale moon. It is a sight that will be never seen again, and the living generations, who regard each other with increasing suspicion, all share this moment. We drew it down, it draws us up, up into a hinterland of dust and lost souls.

Dreaming the End of the Aeon of Christ

The solution is instead found in shaping the way that space is dreamt about, how it is understood, and how we will reach it. It is this subject which he treats throughout the rest of the book, not through philosophical prose but rather through an exploration of the figure of the Antichrist. Grey does this by looking at the histories of two men significantly responsible for our current conception of the meaning of space and off-world exploration: Jack Parsons and L. Ron Hubbard.

Beside being erstwhile friends and rivals, both men shared an obsession for occult rites that would undermine the “Aeon of Christ,” what we can perhaps also describe as the Western Capitalist Democratic order in which we are still fully trapped. While most are not accustomed to seeing this order through an occult lens, nor do many even know about Hubbard’s relation to Crowley and Thelema before the founding of Scientology, Grey’s work makes a startlingly strong case that both L. Ron Hubbard and Jack Parsons were essentially magician-scientists.

Like the magician-scientists with which I started this review, both men—and of course Crowley before him—shaped the sort of questions that are asked and the sorts of technologies that are envisioned which delimit what is thought possible. That is, they were scientific fictionalists in the way the best science fiction functions—giving visions of what might be to those who later will try to make those things be.

This point makes the bulk of The Two Antichrists—which focuses on these two men—interesting not just for those particularly interested in Thelema, Parsons, Hubbard, or Crowley, but also anyone curious about how a reshaping of revolutionary imagination might be affected. Regardless of the legacy of the Church of Scientology, L. Ron Hubbard was a significant force in how space, off-world exploration, and science itself are seen in the popular mind, and there would be no communications satellites constantly orbiting our planet and tracking our moves without Parson’s occult-motivated experiments.

What else might be possible when someone straining to hear voices from the stars tries to interpret those esoteric messages into the world of men? In countless cases, the results have been disastrous yet undeniably world-changing. As Peter Grey says in the ending of the first section of The Two Antichrists:

Ours is now the aim of science fiction and the method of witchcraft. Though it is right to scorn false hope, we must engineer for miracles. The pursuit of science has always been the province of magic. If you feel crushed of hope, then do the work; there is not other path to salvation. Work is where inspiration arises. You are the radical thinkers, do no limit your field of action, do not close off your limitless potential.

The Two Antichrists by Peter Grey can be ordered here.

Below is an audio reading by Rhyd Wildermuth of the first section of the book. The audio file can be listened through the audio player or downloaded as an .mp3.

Rhyd Wildermuth

Rhyd is a druid, a theorist, and the author of Being Pagan: A Guide to Re-Enchant Your Life. He is the director of publishing for Ritona a.s.b.l., lives in the Ardennes, and writes at From The Forests of Arduinna (rhyd.substack.com).