Sacred Hunter: A Tale for the Eve of Samhain

The full moon has not yet risen. I tread slowly over the arid land, lighting each footfall with purpose. So as not to step in cacti. So as not to step on twigs or dry leaves, so as not to make a sound. There is a slight rain falling. That same mist of rain that, at the onset of Autumn, makes even this arid landscape yield the odd bloom of mushrooms, in those depressed spaces where shadows form strange embroideries at the foot of lonesome pines.

This is my third foray in the past day or so. My third time paddling across the river to the other bank. The wild bank, beyond which poisonous snakes and spiders dwell, bones are bleached in the desert sun, and bear scat seems as commonplace as mullein.

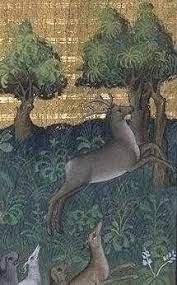

I am looking for deer. At moments sitting motionless, concealed in thickets near the crossroads of game trails. Counting heartbeats till it seems my body is but an extension of the land itself, just another thicket of grey sagebrush rooted to the sand. At other moments weaving silently through stands of greasewood, guided onward by the white patch around the deers’ tails, without which, on an evening like this, they’d be nigh invisible.

The night before I’d been down on the river bank and heard a splash. Then saw twenty pairs of green glowing eyes skimming along the surface of the dark water. Then ran with them across a thrice-shorn hay field. Not hunting then, just content to spend moments in communion. In brotherhood. Follow their hoofbeats, recurve bow in hand, admiring how my razor sharp broad head arrow tips shone silver in the moonlight.

I continue along the trail studying the sigil-like patch work of tracks. There are elk tracks, coyote, deer, and bear. I hear a magpie cry and see it swoop under the pine boughs, and stop to marvel at its queer blue feather, the one it hides between the white and black. I see the black tipped ears of a coyote bounding above tall grass. All is quiet.

A barred owl hoots loudly, breaking the silence. Suddenly a group of deer melt into visibility from out of the underbrush as if they had passed through a waterfall. I stalk them again through stands of greasewood, marvelling how that magical plant harbours desert mice under its roots. In exchange for shelter, the mice offer the plant their moisture-laden breath, moisture much appreciated by the thirsty plant as it ekes out its existence in a xeriscape. We are all connected.

I am downwind from the deer. They are aware there is something close to them, but they know not what. I get within a range in which I’m confident I can make a sure shot. They stand still. I notch an arrow.

As I draw the string back, I exhale deeply so as to slow my heart rate, and mitigate the chance of my muscles moving suddenly in shot anticipation, movement which could alter the arrow’s course. Then that quote from Lorca’s Bodas de sangre [Blood Weddings] flashes across my mind in which a Beggar Woman (death in disguise) petitions the Moon to “Ilumina el chaleco y aparta los botones/ que después las navajas ya saben el camino” (illuminate their vests and open the buttons/ the daggers already know the way in).

In the moment just after I release the arrow, Choice and Chance coalesce, and I forfeit my agency. Both the deer and I are in destiny’s hands now. And like Zeno’s 7th Paradox, the arrow seems to freeze in its flight. I close my eyes.

When I came to where the deer had fallen, I was relieved to see the arrow had directly struck its heart. I confirmed this moments later after field dressing it and removing its entrails. The animal had not suffered. A clean kill is so important to ethical hunting.

The deer is too large for me to haul out of the woods, so I elect to harvest all the meat and return for the bones in the Spring, once they have been cleansed by the mouths of insects. I remove the deer’s hide and spread it fur-side down, and begin to pile the meat on the skin-side. I then wrap up the meat in the hide in a manner I can carry, and head down the ridge to my boat. That night, I had thin venison steaks around the camp fire. Under the full hunter’s moon.

The same full moon that shone only a month prior, before I’d even been able to plan a few days off work and away from family. When I’d retired to my hut in another forest many kilometres away. Lit fires, swept the threshing floor, rattled bones, crackled charms, whispered petitions and prayers, applied lucky powders, and cut the fog that gathers between worlds with my blade.

Evidently, the ancestors had stirred. The Mistress of the Beasts heard my call. And She answered. I was blessed with a deer. Blessed with a deer on the very next Full Moon, exactly one lunation later, down to the very hour.

Blessed to have meat all through the winter (and likely all through the year) with which to feed my family. Blessed to feel connected to my food. No cages, no antibiotics, no chemicals. No plastic packaging ad nauseum. No cruelty to animals. No haemorrhaging of carbon into the atmosphere. No billionaire class who glut themselves off of manufactured scarcity, animal suffering and the destruction of nature.

Under industrial agriculture, acres and acres of habitat are clear cut and destroyed. Chemical run-off from pesticides and herbicides poison the rivers and seas. The soil becomes inert and barren, having had its life sapped from it. Migrant workers are overworked and underpaid. Produce is shipped to all the far-flung corners of the globe, with no heed to carbon footprint or environmental cost.

I have the utmost respect for so many vegans and vegetarians. The ones that live their values. That grow their own food, forage sustainably, and support local farmers. The ones that keep driving cars to a bare minimum and make their own clothes, or at least don’t buy from manufacturers that employ synthetic materials, sweat shop and child labour.

However, we are facing a multibillion dollar industry that caters to the demand of another type of vegan or vegetarian, the type that believes eating Beyond Meat and driving Teslas will save the world. Will save themselves having to make any real changes to their comfortable lives as urban professionals.

Beyond Meat itself is classified as an ultra-processed food, as are many other products marketed to vegans that employ genetically modified soy, palm oil and vegetable oils, the cultivation of which wreaks destruction upon the natural world. This is a green-washed and PC-washed industry that manufactures complacency, at the same time its repugnant capitalist orchestrators profit immensely off of white guilt.

These are the same profiteers that send millions of bees (upon which we all depend) to their deaths in order to industrially farm almond milk; that gain from avocado cartels; that have made it so all the quinoa grown by the indigenous Quechua farmers of Peru — who have grown quinoa as a staple crop for centuries — can no longer themselves afford it. The price now so high due to demand coming from the “first world”. We cannot simply supplant one evil for another.

These are the same profiteers who, along with “Beyond Meat” are now pushing for “beyond” everything. Who are seeking to establish a “MetaVerse” (meta literally means “beyond” in Greek). Who, with their space programs, are pushing a BeyondEarth-future for the super rich.

The same profiteers who will fund corporations such as Beyond Meat, and fund research documenting the negative environmental impacts of the meat industry, but will never breathe a word about the environmental impacts of producing electric cars, or more importantly, of running the internet itself. An operation involving countless towers burning through obscene amounts of energy. An operation that everyone seems to take for granted now.

This is why, in the Dead Hermes Epistolary, we made the controversial suggestion that eliminating one’s participation in the online world, or at least greatly limiting it, may ultimately have a more significant net positive impact on the environment than going vegan or limiting one’s consumption of animal products. Especially when questions of complacency and the time-suck of screen-time are taken into account.

It is strange that an act as sacred and natural as sustainably hunting a deer, an act that should never be political — just as issues of food and housing should never have become political — is a profound act of resistance in the twenty-first century.

A woman who lived in Gaza once told me a phrase she learned there: existence is resistance. The horrible truth is that this is the case for almost everyone on the planet, despite the fact that the extremity of each person’s situation varies widely depending on location, background, skin colour, and other such variables.

For me, hunting is a natural and sacred act. One of the most sacred acts. In witchcraft, there are so many poems and songs, not to mention spirits and gods, that employ the imagery and metaphors of the wild hunt. The sacred hunt is a mystic experience charged with symbolic meaning, and yet the primary mystery of the hunt is not metaphorical, but simply the hunt itself. Similar to the way sex is a mystic experience charged with symbolism, and yet its central mystery is not metaphorical, but is simply sex. (And I’m not just talking about reproductive sex here).

For me, hunting is about connecting to my ancestors, connecting to a memory and a legacy that stretches back to the dawn of human history. It is for this reason, and out of a profound respect for the animals themselves, I was willing to put all the work in to getting my hunting licence, to choose to use a traditional bow and arrow instead of firearms (even though a hunting licence requires you to be proficient in firearms safety). Why I was willing to put in all the work to become a skilled enough archer till I knew I could confidently hit an animal’s vital organs and thereby keep suffering to an utmost minimum. To learn how to shoot with my whole body, with every little muscle. To be aware of the way the wind blows, know proper shot placement, and cultivate the meditative mind state so important to traditional archery. To therefore eschew modern compound bows with their sights, scopes and gizmos, all of which are designed to take the archer and the body of the archer out of the equation.

For me, deer hunting in particular has an additional significance, a symbolic significance but also a political one that has connections to anti-fascism. I found Christopher Scott Thompson’s 2017 article on the fianna in relation to anti-fascism brilliant and inspiring. Cultivating the ethic of a warrior-poet is important to me, as is the identification of the hunter with the hunted. One of my own sons is named Oisín.

Not everyone is in a position to become a sacred hunter. Some of us live in areas where hunting cannot be done sustainably, where game is scarce. Some of us are trapped in cities or trapped in our jobs, unable to get time off work. Some of us, for health, dietary, or other personal reasons, simply would not like to eat meat. And that’s fine. I am not advocating that readers of this story go out and become sacred hunters.

What I am advocating is a radical reappraisal of how we relate to our food, whether animal, vegetable, or both. Where we source it, the environmental impact involved in acquiring it, how accessible it is to all, and who might be making a fortune off of violating the nonnegotiable human right that is access to healthy food.

Revolution will not grow from a conquest of Twitter or a conquest of Mars. It will grow from a conquest of bread, and there are so many things that all of us can do to midwife that revolution. This is imperative, especially since the ability to acquire food from the shelves of supermarkets is a fragile privilege that can be all too easily lost. By climate catastrophe, by truckers’ strikes, by war, and by many other occurrences.

The state thrives off of the illusion that we cannot provide for ourselves without it. That without it, we will be sitting ducks in a world that is red in tooth and claw.

It is here we may find new meaning in the motif common to Celtic myth that chasing the sacred deer relates to questions of kingship and sovereignty. That a successful hunt is a claim to power. In our terms, however, this is an anarchic sovereignty that does not necessarily seek to abolish all kings. Instead, it seeks to affirm that each and every one of us is a king, is a queen, is a star. We are all sovereign.

Producing your own food, or participating in a thriving sustainable local food system, is not as inaccessible as you might think. Even for the landless. Even for those who live in cities. I have much to say on this, but it will have to be a subject for future articles.

For now though, I’d like to extend my best blessings to one and all. For tonight is the Eve of the Feast of Samhain, and the Dead are on the wing. There will be venison stew over at Slippery’s place. Prepared with homegrown praties, sweet onions, thick carrots, purple kohlrabi, plump golden turnips, and peas like wee pearls of moss agate. It shall be served with soda bread and accompanied by a few drops of blackest stout and reddest wine. Wine and song will flow freely and the Dead will be rightly supped. I wish you all good health and full bellies throughout the Winter season, and ever onward.

Oíche Shamna shona daoibh!

Slippery Elm

is the author of The Dead Hermes Epistolary (Gods&Radicals Press: 2019). Once an itinerant poet and dancer, he is now a full-time mixed vegetable farmer who grows for a CSA food box, in which a substantial number of boxes are free for people in need, as well as for a “pay what you can” community farm stand.