Virtual Vandalism and the Dispute Against Leftists

“We mistakenly attribute the concept of vandalism to what is ‘marginal,’ and rarely to what is ‘central,’ when the term should apply to infringements against the integrity of public property in general. […] Vandalism is, therefore, the attempt to destroy property even in its abstract form — the body and identity.”

Leia em português na Le Monde Diplomatique Brasil.

Photo: Fabio Teixeira

In June 2020, shortly after the attempt to criminalize anti-fascist movements in the USA and Brazil, a secret group was created on Facebook with the aim of mocking and harassing leftists. Despite not considering myself as a leftist or posting content in defense of leftist political parties, I was targeted by them in December. My participation in a group of vegetarian and vegan recipes was enough, which goes against the values of entrepreneurial freedom and ‘sustainable exploitation’ of the livestock industry that the members of the mockery group proclaim. Despite appearing childish and harmless, the group has a clear purpose of destabilizing emotionally, opening legal processes, and intimidating its targets to withdraw from the virtual public sphere. I know this because I infiltrated, observed, and contacted other people who were affected by this self-proclaimed digital militia.

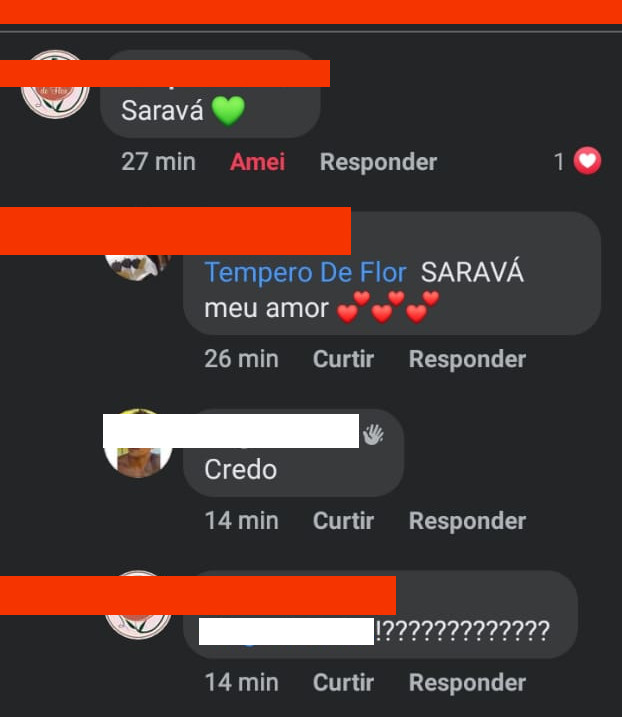

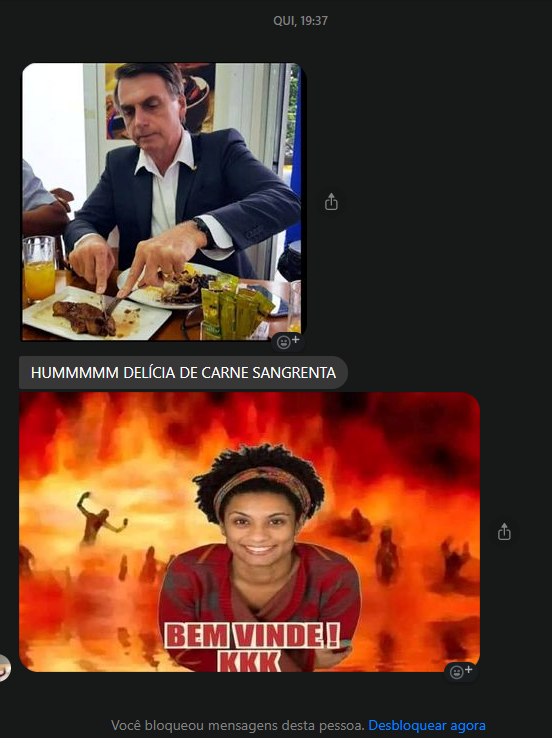

I have been in several vegan and vegetarian groups on Facebook for years. For the first time, I started to ‘attend’ one that was ‘public.’ On the second day, I realized that all the posts and comments had hundreds of “haha” reactions. Eventually the comments included pictures of meat, I started receiving private messages with photos of Bolsonaro eating barbecue, and other members received hostile comments against religious expressions of African origin. It was only when they moved to my personal profile that they managed to grab my attention. A public post about the death of a writer and poet with whom I worked received more than 50 ‘laughing’ reactions. Her family was tagged on the post, and my heart sank with the idea that they saw so many of these notifications at such a delicate time.

Other members of the vegetarian recipe group chose to withdraw from the public sphere, making their profiles visible only to ‘friends,’ and closing the group. As a writer and public figure, this option would have had negative professional repercussions, and I did not believe that this would be a solution. Facebook's attendants suggested the same — “Report accounts and close your profile.” For 3 days, I reported about 500 accounts, and more kept showing up. They found my professional page, started attacking people with whom I work and friends who happened to share my work — it was a contagious tribulation.

“Bolsonaro OUT and all coup-supporters”. Photo: Fabio Teixeira.

The dispute I entered was not instigated by divergent partisan affiliations, but by the threat to the integrity of my existence in the public sphere. It was as if a group of people had traveled a good distance with the sole intention of getting close to me and damaging my belongings. As a Facebook customer, I pay to promote content on the platform, and that means I can contact attendants directly in a situation such as this. When they told me that the solution was to withdraw from the public sphere, it was as if the people I paid to maintain a public square told me that I should simply stop attending if I do not wish to suffer physical or moral damage. The dispute, in addition to being ideological, was about my right to exist in public without having my belongings vandalized, or my psychological well-being threatened.

After contacting attendants half a dozen times trying to report what happened, or at least to find out where these people were organizing, I was not confident that the attendants I was talking to worked for Facebook. Several recently published articles reveal that the corporation outsources and saves money in one of the most crucial areas of its maintenance — the safety and well-being of its users. They certainly also do not care about the well-being of these outsourced employees. Facebook content moderators deal with violence of unimaginable magnitude on a daily basis; things much worse than what these bullies from the mockery group were doing to me and my colleagues. In all varieties and levels of moral damage and traumatic imagery, there is no doubt that the resources to deal with them are available, with the company profiting more than 18 billion a year.

In addition to not doing enough to ensure the well-being of users and moderators who are exposed to hostile and traumatic content, privacy policies appear to exist selectively. While it is impossible to discover, without legal measures, which group hundreds of accounts belong to, data such as who placed what item in the electronic basket of a virtual store external to Facebook are routinely sold to advertisers. As someone who buys ads on the platform, it was clear that there is a willingness to sell user data when the intention is to advertise a product. However, data of users who threaten the integrity of my virtual business and the emotional safety of my community is protected.

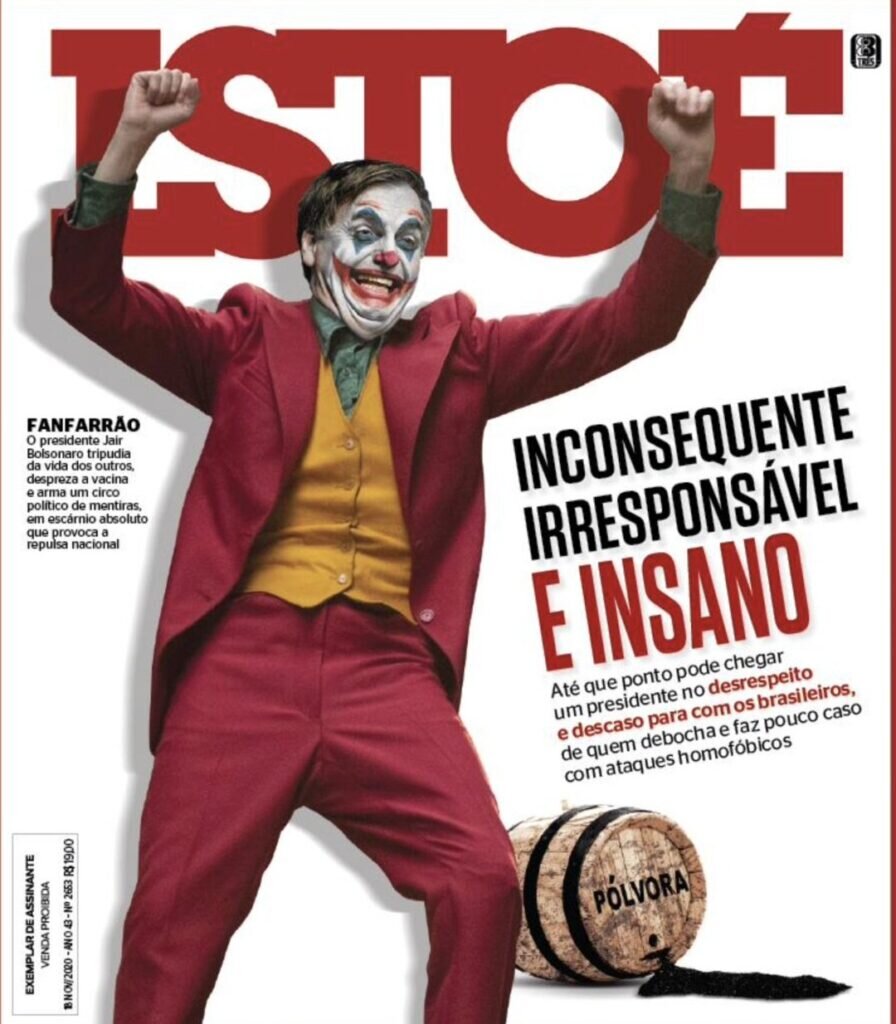

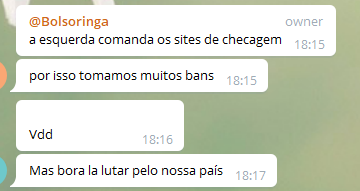

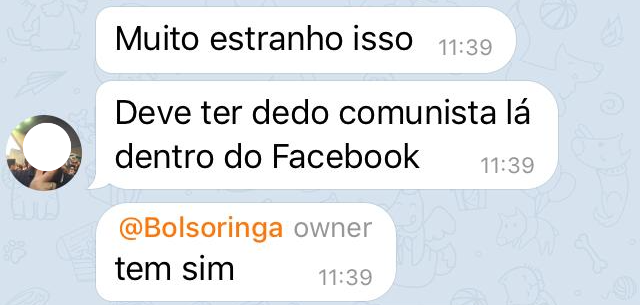

Even without the help of Facebook attendants, who are just as victimized by the corporation’s twisted priorities as I am, I managed to locate one of these bullies’ nests. An image of Bolsonaro dressed as the Joker, photoshopped in different contexts, was present in many of the profiles that invaded my account. In the first half of November 2020, the Brazilian magazine IstoÉ published a critical cover depicting Bolsonaro as the Joker and calling him “irresponsible” and “insane.” Soon after, several Bolsonaro supporters organized themselves to idolize the Bolsoringa (“Bolso-joker”), viralizing a hashtag and creating groups on social media. First, I joined the closed group called “Bolsoringa,” moderated by a famous right-wing comedian/reporter, which had 33,000 members before being shut down for incessantly propagating Fake News about the pandemic, health safety measures, and the vaccine. In the Telegram group (the alternative to what they believe to be Facebook censorship) there is concern about the veracity of the sources, not because it is misinformation and sends the wrong message to the community, but because it can have consequences if identified by infiltrators (like me). They, like many leftists, also feel betrayed by Facebook’s community standards, whose interests have become clearer than ever — their own profit, as opposed to a particular partisan interest.

The irony is that capitalism, free of governmental restrictions, is the strongest political current in this same community that feels wronged by the policies of the largest social media corporation in the world. Excluding pages like theirs is good for business, but it is seen as an injustice by the people who defend laissez-faire. Although legal proceedings against Facebook in recent years seem to infringe Zuckerberg’s right to individual freedom, in reality, nothing has done more to help him keep his corporation relevant and desirable to its consumers. Unfortunately, we cannot count on the company’s anti-racist and anti-homophobic initiatives as a political, but an economic stance. It is undeniably profitable to accommodate the black and LGBTQ+ community to the platform. Part of the frustration of members of these Fake News and right-wing bullying groups is the feeling that they are gradually becoming less relevant to the very system they idolize. Therefore, to them, the explanation can only be that there are “communists inside Facebook.”

The Secret Group

Photo: Fabio Teixeira

In the beginning, being bombarded by thousands of notifications from hundreds of accounts a day made me feel outnumbered and vulnerable. I thought, ‘could I mobilize a thousand individuals for some simple purpose online?’ Perhaps a defense mechanism and disbelief made me think next, ‘are they bots?’ Luckily, a member of another group found me because he felt that it was unfair to attack vegetarians. He, as a “protector of animals,” thinks that vegetarianism “has nothing to do with the left,” and that the attacks should be aimed only at people who “deserve it.” According to him, whose online pseudonym is ‘Laisa,’ content that “deserves to be made fun of” include: “support for previous governments,” the “spread of illiteracy” through gender-neutral language, “illegal” allegations of fascism, and “campaigns about privileges instead of rights.” In other words, the target is those who publicly defend the Brazilian Worker’s Party, the trans, anti-fascist (Antifa), and anti-racist community.

I will not deny that I have political motivations for being a vegetarian. The industry is violent with animals, with the environment, with our bodies, and I avoid financing it as much as possible. When researching some of the individuals who invaded my profile and bombarded me with mocking messages and thousands of “haha” reactions, I noticed that some of them had a direct relationship with the dairy industry and governmental agribusiness institutions. The account of a man stood out for listing a bankrupt dairy distributor as his place of work, with a series of open lawsuits, including one with the State for selling food that was unfit for consumption. In addition, I also noticed the account of a civil servant of the State Agency for Animal and Plant Sanitary Defense (IAGRO); an employee of a large non-vegan candy company; and a senior technician at the ‘Information Technology department’ of the Court of Justice of Mato Grosso do Sul state, who is possibly the son of the superintendent of the Brazilian Institute of the Environment and Renewable Natural Resources in that same state (they bear entirely the same name except for the word ‘Junior’). As one of the poles of the livestock industry in Brazil, the fact that there are civil servants of the Justice Department of Mato Grosso do Sul state involved in an online group of mockery against vegetarians and leftists puts into question what the ideological motivation behind this initiative could be.

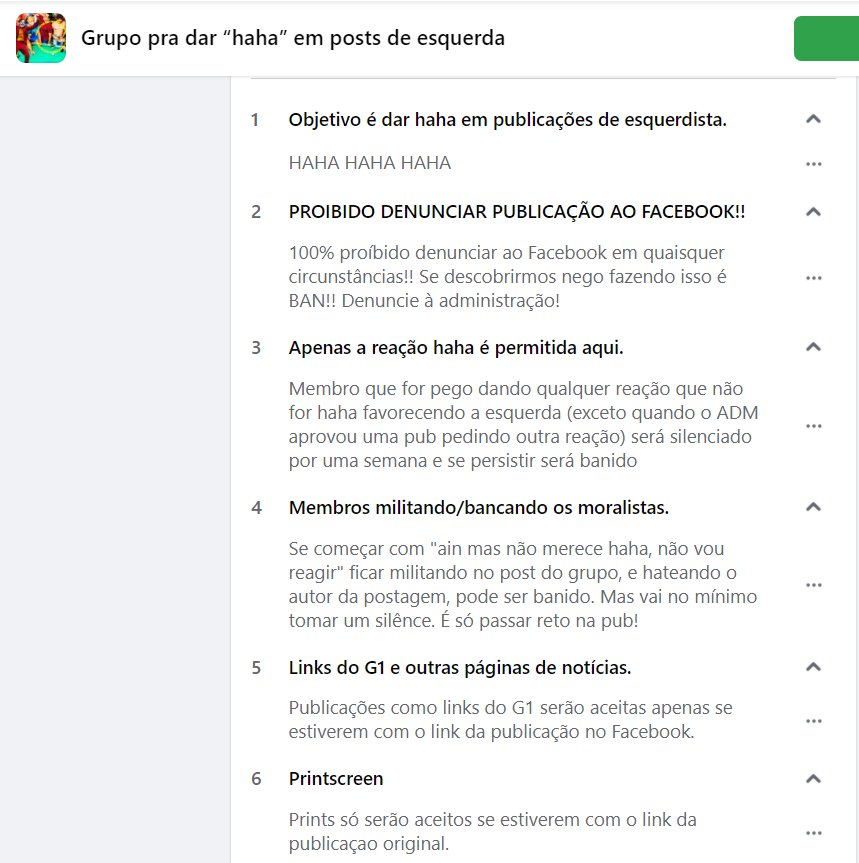

Thanks to my source, Laisa, I found out the name of the group where these people were organizing: “Group to react ‘haha’ on left-wing posts.” However, the group was secret — it was not visible to anyone who was not invited. I spoke again with a Facebook attendant, sent them a list of account names, the name of the group, and a link to the group that, although it wasn’t visible, appeared as “deleted” or “restricted.” For some reason, after warning me that they could not make any guarantees or keep me informed about the progress of my complaint, the next day, the group went from ‘secret’ to ‘closed,’ and I asked to enter. When I joined, the intimidating nature of the number of people involved and the political strategy behind it was demystified. There, I saw many of the people who attacked my page, and more. I was able to access the list of almost 8,000 members and contact other people who also became their targets.

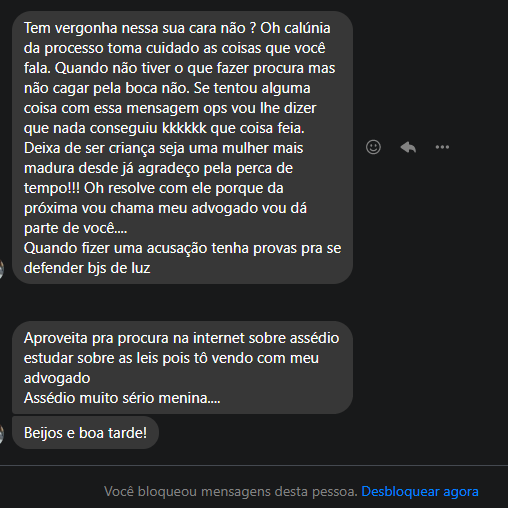

The first thing I noticed when I joined the group was the superficiality with which they chose their victims. It was clear that the members of this laughing group did not read my work, and their criteria relied heavily on what they perceived as the leftist aesthetic, more so than ideological rhetoric. In my case, the aesthetic was to give advice on how to cook banana peel — I publicly announced that I am a vegetarian in a particularly mockable way. Other people became targets for using trans, feminist or communist symbols, slogans in defense of the public health system (SUS) or body positivity, the color red, the word ‘Lula,’ etc. Unfortunately, this does not mean their behavior ceased being perceived as harmful. When a victim became emotionally destabilized, and reacted aggressively in private messages, they boastingly shared screenshots on the group. And when they managed to frame what the person was saying as slander, they announced they were going to sue, flaunting the message as if it were a trophy.

Seeing this happen to others was a reminder that it had also happened to me. When I wrote that mass laugh-reacting to a post about someone’s death was ‘harassment,’ someone replied to me: “oh, slander gets you sued, watch out for the things you say... don’t shit out of your mouth [...] stop being a child [...] I will call my lawyer, I will give you a piece [...] have the proof to defend yourself [...] I am checking with my lawyer Very serious thing, harassment, girl...” This confidence that it was them (and not me) who would be protected by the law puzzled me. The individual did not consider that the word ‘harassment’ does not apply only to offenses of a sexual nature, but certainly the legal term ‘cyberbullying’ is more accurate — “intimidating, assaulting, causing pain or suffering, anguish or humiliation to the victim, including by means of social exclusion.”

The Dispute for the Law

Photo: Fabio Teixeira

Many of the people I spoke to who were targeted by this group had an instinctive reaction to sue, without knowing how. However, many of the members of this ‘virtual militia’ are professionals in the area of public and private security. Even before I infiltrated the nest, I noticed that many of them were policemen, security guards, marines, snipers, etc. In addition to those who claim to be lawyers and civil servants across the country. The culture of mockery and intimidation was encouraged by the highest authority of this nation’s executive power, so it is difficult to count on the legal system that is sustained by that administration.

In 2020, the Brazilian right-wing administration somewhat instigated this cyberbullying movement with the amendment of the anti-terrorism law criminalizing anti-fascist groups. On May 31, Reuters reports that President Trump responded to Black Lives Matter protests by designating “Antifa as [a] terrorist organization” (Reuters). The following day, June 1, the Brazilian Chamber of Deputies is presented with a request to amend the “Antiterrorism Law No. 13,260, of March 16, 2016, in order to classify ‘antifa’ (antifascist) groups as terrorist organizations” (Portal of the Chamber of Deputies). During the first week of June, a 999-page PDF started circulating on WhatsApp with detailed information about people who present the antifa aesthetic online (tattoos, piercings, the antifa logo on their profile, belonging to anti-fascist Facebook groups, etc.). This same week, a trend of personalized anti-fascist logos dominated Brazilian social media. June 18, the “Group to react ‘haha’ on left-wing posts” is created.

As Laisa (my source) pointed out, one of the purposes of this group is to make fun of those who supposedly mischaracterize the concept of fascism by applying it out of context — which, to him, is criminal. Not only does the law support this sentiment, but there was also an initiative to at least threaten to put this law into practice against certain individuals, through the creation and distribution of the list. In creating the group, the intention was to appropriate the law, instead of breaking it. When there is not enough ‘evidence’ for a legal process, the next best option is to coerce the leftist, antifascist, trans person, etc. to withdraw from the virtual public sphere. In the meantime, there are people mentioned in this ‘antifa PDF’ who have also appropriated the law and are suing politicians who are allegedly, somehow, associated with the list. This fierce dispute over ‘Rights’ relating to the digital realm symbolizes how much resistance movements against the status quo are exiting ‘the underground’ and becoming mainstream in the (real) public sphere.

The Public Sphere

Photo: Fabio Teixeira

Returning to an underground, stigmatized, or timid existence is far from the solution. But when people who have existed freely in the past feel coerced to occupy that timid and restricted position for the first time, we cannot expect them to accept it with pleasure. For them, there is no greater injustice than being placed in the subordinate position in which they usually put others. One of the videos shared in the ‘Bolsoringa’ group reveals that, for them, Bolsonaro is an example of how society unfairly restricts the freedom of speech of people on the right. In his interview on December 28, 2020, the president at various moments alludes to things he cannot say, and the audience laughs, agrees, and shows that they know what he wants to say even without him saying the words. “I'm not even going to make a joke here because they say later that I’m mocking...” and laughter erupts as if he had made the joke.

In addition to the so-called injustice of the mischaracterization of fascism, and an alleged attempt to silence people like the president, Laisa also pointed out the importance of distinguishing between privileges and rights. In a way I agree, there is no need to denounce the privilege each member of this group may have, instead of recognizing their right to exist and organize. However, to reject the concept of privilege while being indignant at leftists’ media privileges is incoherent. For them, the problem is to point out privileges of race, gender and class, instead of fighting for rights as individuals. Certainly, as individuals, we should have the right to exist in the public sphere without becoming targets for mockery, bullying, and harassment. Perhaps proudly existing as a trans, feminist or black woman infringes the freedom of “Bolso-jokers” to express themselves freely without being labeled transphobic, sexist or racist. It is the epic battle of the Brazilian polarized political conjuncture, the tug-of-war between ‘change’ and ‘tradition.’ It seems to me that many do not accept the fact that Facebook, the mainstream media, and the capitalist machinery which moves them may not be married to the ‘tradition’ team, but to their own profit instead. Therefore, the right is given to those with the privilege of being more profitable.

What are, then, our rights in the public context of social media? Our Facebook feed, in a way, is the wall around our private environment. The process of selecting what is visible to the ‘public’ or to ‘friends’ is a decision based on which side of the wall we want to display something at that moment. In the United States, it is common to place flags or signs on the front lawn of suburban homes. Even if these objects are intended to be displayed to the public, they are still personal property, and when strangers damage that property, it is considered vandalism. Publicly posting something of a political nature on my feed is nothing more than a sign on my lawn, or a sticker on my car. My Facebook page, my house, and my car are personal properties, and for an anti-communist community, these should be as sacred as private property. However, this is not the case.

Ideological inconsistencies point in the direction where the clash is outside the sphere of partisan politics. It is outside the sphere of opinions and debates. The clash is between people who want to exist and those who do not want them to exist. I do not consume meat, it’s the relationship I have with my body, and members of that mockery group don’t believe I should exist. There is no exchange of ideas, or the possibility for dialogue. There is only the belief that people like me should not exist. For them, fat or trans people should not exist either, much less proudly and in public. Vandalism is, therefore, the attempt to destroy personal property even in its abstract form — the body and identity.

Vandalism

Photo: Fabio Teixeira

In its classic use, as destruction of public or private property, the term ‘vandalism’ is a tool to criminalize marginalized people who dare to occupy the central and collective space. People who were already central in the urban and financial sphere enjoyed complete control over the public environment, and its collective use. A high-end store, for example, could not only design the building on its own patch of land, but also visually pollute a radius of a kilometer and even change the direction of car flow on the street. In other words, we mistakenly attribute the concept of vandalism to what is ‘marginal,’ and rarely to what is ‘central,’ when the term should apply to infringements against the integrity of public property in general.

As street art started to become profitable, the legal and corporate dynamics with the word ‘vandalism’ changed. In 2007, São Paulo banned billboard advertising, starting an era of murals and vertical gardens that gave new meaning to the concept of public patrimony, and the role of the population in the construction of the collective space it uses. Almost 10 years later, street artists won a lawsuit against Nissan and its marketing company because “the video with the vehicle’s advertisement” exposes the “work of the artists” for 4 seconds. The concept of visual pollution was reversed — with it, the position of street artists moved from margin to the center — and the law, as well as advertising, had to keep up with this change. In this sense, the law is nothing more than a tool for improving the capitalist practice, rather than a restriction of it.

The members of the “Group to react ‘haha’on left-wing posts” have appropriated this vandal tactic, leaving their hundreds of ‘spray paint tags’ in the form of “haha” reactions on posts from random people on Facebook. Although they are not marginalized by the status quo or use this tool to fight for the right to access the public sphere, the term ‘vandalism’ easily applies to them. Anti-government rhetoric (excluding Bolsonaro) leads them to reject public property as legitimate, and at the same time to enjoy free access to it — as the high-end store renders graffiti illegitimate while indulging in billboards. For this reason, their virtual vandalism is a tactic to remain as central in the public sphere, while deciding who deserves to occupy that space with them through cyberbullying.

A community that already occupies a central position in society is likely to take up this project because it feels threatened. Their cisgender, capitalist bodies, blind to racial issues, etc. have represented the ‘normal’ for at least a hundred years. What could have shaken the structure of this normativity? The artist Leonard Koren, when trying to describe the essence of Japanese Zen aesthetics, states that “repetition is the essence of tradition.” In a way, leftism strives to interrupt a certain repetition, but not always in order to destroy tradition, but rather to reconfigure it. The capitalist tradition is constant reconfiguration, and Facebook is a perfect example of that. Whenever it deals with a legal process, it is compelled to correct a detail of its configuration, so it does not collapse or grow to the point of becoming a Nation State (with a single profitable resource for export). In other words, what “Bolso-jokers” call “communism” is, in reality, the manifestation of the feature of capitalism which is most essential to its permanence — adaptability. And, frankly, the Brazilian Worker’s Party style of “communism” was nothing more than an attempt to expand the class of consumers, reducing the marginalized contingent of the population which was subject to extermination (through poverty and exclusion).

Anti-fascism, like communism, needs to be contorted to fit a threat to ‘tradition.’ If fascism is not the tradition, why would anti-fascism be a threat? It is necessary to assess how the struggle for anti-racism, LGBTQ+ rights, and the population’s access to health and basic resources, when framed as an anti-fascist struggle, intimidates avid defenders of capitalism and freedom of expression. The tradition of individual freedom could, and should, include at least the freedom to practice a religion other than Christianity, to identify as LGBTQ+, black, fat, vegetarian or vegan, etc. Anti-fascism fights for nothing more than the right of these individuals to exist. And historically, the term is based on the simple fact that fascism appropriates nationalism to exterminate undesirable contingents of a population. We put “Brazil above” the lives of everyone on the margins, and the vast majority of “we, the people.”

Finally, the most important ends up being the simplest — we have the right to be who we are, freely and openly. Society, in real and virtual life, not only can, but must adapt to accommodate the people in it. “Bolso-jokers” also exist in this society and deserve attention; may they continue to display this attention as a trophy. However, how can we embrace those who endorse our extermination? History, its conflicts and technologies, inevitably advance, and we exist in symbiosis with it. As long as there is resistance to preserve repetition (tradition), there will also be a fight for the rights of a new generation and its new historical context — their right to exist.

ScreenShots

Mirna Wabi-Sabi

is site editor at Gods and Radicals, founding member of the Brazilian magazine Enemy of the Queen and of the Plataforma 9 media collective.

The award-winning photojournalist Fabio Teixeira is also a founding member of Plataforma 9.