Voice of Mother Tiger

Noticias de pleamar:

Querido cómplice aquí los Vimaambies y su corazón MAAM a la respuesta... Llegó tu carta escrita y la contesté pero aunque te parezca mentira, aun no he juntado para el sello… te la mandaré la próxima semana. Agosto ha sido como su sol canicular, mortífero y despiadado, pero con todo hemos tirado "palante" y aquí estamos vivitos y coleando como dicen en mi tierra.Tus cosas duermen tranquilas y se han incorporado a la casa sin problemas… Por supuesto que puedes quedarte aquí hasta que encuentres tu casa a la vuelta, tu amor vimanvie es grande y nos llena de dicha a todos, Compañero de palabras y sueños noveles. Aparte la economía RAÍZ Y DUENDE crece como árbol de amor y consuelo, cuando vuelvas habrá nuevas bailaoras y haremos juntos recitales y poéticas. y que la creación te acompañe. Abrazos de sueño y de viento desde el sur

— MAAM

El 31 de agosto del 2013

News of the Tide:

Dear accomplice, the Vimaambies and their heart, MAAM, here at the reply…Your written letter arrived and I responded to it but although you might think it a lie, I still haven’t got together [loose change] for the stamp…I’ll send it to you next week. August has come with its canine, deadly, and ruthless sun, but we’ve all pulled forward and here we are [still] living and wriggling as they say in my land [Jaén]. Your things are sleeping peacefully and have been incorporated into the house without problem…Of course you can stay here until you find a home upon returning, your vimaambi love is grand and fills us all with bliss, Companion of words and novel dreams. The economy aside, ROOT AND DUENDE is growing like a tree of love and comfort, when you return there will be new bailaoras [dancers] and together we’ll do [more] recitals and poetry nights. And may the [new] creation accompany you. Hugs of dream and wind from the South

— MAAM

Aug 31st, 2013

***

These were the last words expressed to me by one of my dearest friends, a poet, mystic, healer and revolutionary who changed my life forever. A mere five days after writing me this message, on Sept 4th 2013, seven years ago today, María de los Ángeles Argote Molina, known to her friends and family as Ángela or MAAM, passed away suddenly in the night.

And so Spain lost one of its greatest yet heretofore unsung luminaries. Nonetheless, MAAM is destined to be remembered as one of the towering and major literary figures of the 20th century, and indeed since the very inception of Spanish letters. Her works will come to be studied alongside those of “golden age” greats such as Fernando de Rojas, Cervantes, Lope de Vega, or Luis de Góngora y Argote, and the radical “silver age” writers of the Generation of ’27. This posthumous rise to prominence is inevitable.

MAAM left us with an enormous oeuvre that has largely remained unpublished. Her works range from short lyrics, so charged with music and magic that blue sparks and moths of every colour leap off the page, to her magnum opus, the epic poem in three acts. El llanto de la Amarga, or Amarga’s Weeping.

She once told me that I had come into her life to take on her “trazo” which I think is best translated here as “brushstroke”, not only due to the way poets “paint with words” but because MAAM wrote most of her poems as spiralling calligrams. For an example, see here. She abhorred the straight line.

MAAM mentored me, took me under her wing, and taught me many things. There was never any doubt in my mind that I would eventually help curate her legacy after she died, although how soon this was thrust upon myself and others did come as a very painful shock. Now, her family, myself, and the other surviving artists, poets, and musicians in her circle have taken it upon ourselves to carry her torch forward.

Of special mention here is her widowed partner, filmmaker Vincent Biarnès, who is leading and spearheading this task, and tirelessly working to digitize hundreds of hand written and type written manuscripts, as well as fearlessly introducing MAAM’s work to the mouldering Spanish literary establishment, in ways as fresh, radical, uncompromising, and recalcitrant as the work of the poet who was his best friend, co-parent and life-long love.

I, the poet Slippery Elm, have been translating Amarga’s Weeping into English. Before continuing with this initial introduction of MAAM, I would like to publicly announce we are seeking a publisher with bravery and beauty enough to help us share MAAM’s legacy with the world.

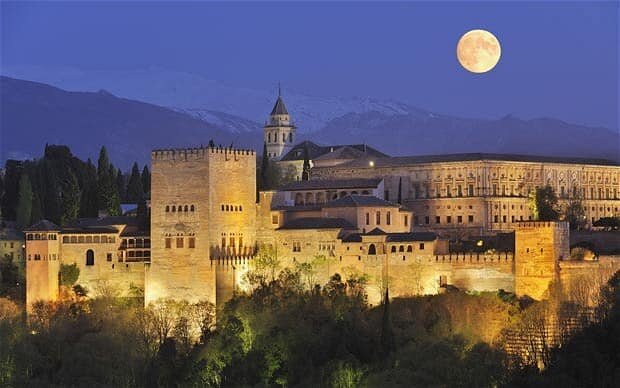

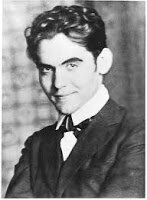

I could tell you many stories about MAAM. The details of her time as a clandestine radical leftist militant in Francoist and post-Franco Spain. Or about the thirteenth century Moorish tower (from the time of the Almoravids) where she wrote poems and dried herbs. How it was full of skulls and candles and how the two of us worked together up there on translations of her poetry. Or how she considered herself a descendant of Sappho, and how copies of Sappho, Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, and a leather bound complete works of Federico García Lorca were found lying on her altar after her passing. Or how she cried in the womb, and was trained by Andalusian witches in the art of healing, and over the course of her life, healed many people of herpes and other afflictions, without ever charging for it. Or how on one occasion she said to me “Soy bruja, soy bruja brujísima” [I’m a witch, I’m the witchiest witch] and on another occasion said “Esliperín, no somos brujos, somos santones” [Slippery, we’re not witches, we’re holy men/women/people].

Or I could tell you about the Taller de Arte Vimaambi, a gallery and intimate performance space she co-founded, about how it was a beacon for young artists, poets, flamenco musicians, and radicals, and how many of the same people who got their start there have gone on to become established figures in their respective art forms. I could tell you about its wooden door carved with duendes and gargoyles, dating from the 1920s when Federico Garcia Lorca and Manuel de Falla roamed the streets of the Albayzín. I could tell you of her flamenco group Raíz y Duende [Root and Fairy] and how she invoked the moon goddess at each performance in wailing funerary tones.

All of this will have to wait for a future encounter. I will just say a few more things before passing the mic to Vincent, who will cover the concrete details of her biography. But first, a bit more about Amarga’s Weeping.

***

Amarga’s Weeping, or El llanto de la Amarga is an epic poem in three acts. It was written over the course of ten years and underwent a period of thorough polishing for an additional three. The epic revolves around a simple yet potently taboo premise: the imminent destruction of the universe.

Following the adventures of protagonists Agreste and Crisálida across the worlds, we encounter a spiritual ecosystem home to a rich dramatis personae of beings, such as El Silencio el Amarillo (The Yellow Silence), La Muerte (Death), La Tiniebla (The Deepest Darkness), or divine creator beings such as El Gran Mago Sideral (The Great Sidereal Mage) and La Soledad Primera (The First Solitude).

While containing echoes and parallels in other mystical and philosophical traditions and works, such as Neoplatonism, the Kabbalah, or Dante's Comedia, Amarga's Weeping offers a unique take on poetry, mythology, cosmology, cosmogony, and philosophy. This is a work of immense breadth and depth, executed with the epic flare of Homer, and the heart-flooding lyricism of Sappho. It earns MAAM her place in a long line of poets and philosophers that encompasses both the epic and lyrical registers found in the infamous Soledades of her own direct blood ancestor — Don Luis de Góngora y Argote — and stretches back to the mantic sybils, rhapsodes, and high priestesses of the ancient Mediterranean world.

***

I am immensely lucky. Lucky to have known and learned from this extraordinary person, and luckier still that I was able to say to her everything I wanted to say, before she died. This is an opportunity that is rarely afforded to most people who lose loved one’s suddenly.

Driven, perhaps by some premonition, I wrote her an ode. And recited it to her one night around the camp fire at her family’s hideout in the mountains beyond Granada. In this ode, I said everything I would have said to her if she was on her deathbed, or, that I would have said if I were writing her an elegy. She was very moved by this ode, and happy.

But it still gives me chills to recall how a shadow came across her face. That night in the mountains was the night before I was to leave Spain for a few weeks and make a trip to Northern Europe. All of a sudden, she became very serious and said. “Me pregunto cuándo nos volveremos a ver” [I wonder when we’ll see each other again]. Somewhat surprised, I asked why. She answered “Porque ahora te vas y a veces aunque esté en tu corazón volver, como a Ulises, los vientos del camino te podrían desviar y no sabemos por cuanto tiempo…” [Because now you’re going, and sometimes, although it be in your heart to return, like Ulysses, the winds of the road may blow you off course, and we don’t know for how long…”]

In the end, I returned when we had predicted I would. Only, when I got back she was already gone.

Thank you for taking the time to read this, friends, and allowing me to share personal experiences. I hope you find MAAM and her work as inspiring as I do.

¡No pasarán!

***

María de los Ángeles Argote Molina, MAAM, Ángela Argote, or simply Ángela as we all called her throughout the last 20 years of her life, was born on the 14th of July in 1955, in a house on the plaza de la Magdalena, in Jaén.

HER FAMILY

Her father, Ángel Argote San Martín, was son of an at one point wealthy Jaén family, Republican but rightwing. Her paternal grandmother, was Rosa San Martín, born in Buenos Aires, relative of general José de San Martín, “libertador de Argentina”.

Her mother Ascensión Molina Ramón, became an orphan not long after she was born. Her maternal grandfather, Pascual Molina, shoemaker, and militant of PSOE (Partido Socialista y Obrero Español, eng. Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party) and the UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores, eng. General Workers Union) died in the civil war. Her maternal grandmother became a widow with three children at a young age and suffered the humiliation of many Republican women, having her head shaved publicly in the bull fighting ring in Jaén. When the conflict ended, she served as a maid in exchange for only a plate of food and a few leftover scraps per day with which to feed her three children: Ascensión, Manuela and Julio.

Ascensión, Ángela’s mother, did not have any other choice but to begin to sow a few years after being born, an office she learned from a local seamstress from the Caños neighbourhood. At age 13, she installed a workshop in her own house, where she tirelessly worked more than fourteen hours a day.

Ascensión and Ángel were married, without the blessing of the groom’s family, and the young couple moved into an old apartment in the ancient Plaza de la Magdalena, the same plaza that houses the same cave that, according to legend, the “lizard (dragon) of Jaén” once dwelt. Across from this cave, Ángela was born, and three years later, so was her brother Manuel.

FLAMENCO

Back then, she had a famous neighbour, the flamenco “cantaor” [singer] Juanito Valderrama, author of the popular song “El emigrante”, who would become one of her first idols. This gave her a great love of flamenco and years later she would end up collaborating closely with young artists, practitioners of singing, guitar, and dance, in the creation of diverse performances. She recited her verses, always accompanied by guitar or piano, as a rhapsode of impressive talent, and supplied lyrics written for fandango, soleá, taranta, tango, alegría, or bulería flamenco styles, for her companions to sing.

POETRY AND STUDIES

In a Jaén depressed and severely punished by Francoist repression for being the last Republican province to capitulate to the fascist forces, she stood out from a young age for her intellectual curiosity and a character full of rebellion that she would continue to develop over the course of her life. In 1961, at only 6 years of age, she received a prize from the bishop of Jaén, the catechism, for knowing and being able to recite the entire mass in Latin. This same year, Ángela began to write poetry, something she would never stop doing throughout her whole life.

She lived in a house where books simply did not exist and despite that, or perhaps because of that, she acquired a great love of reading that astonished her family. She studied with nuns in the Caños neighbourhood. In accord with the mentality of the era, she first registered in the course “for poor girls”. Soon, however, having caught the attention of the nuns with her unmistakable intellectual gifts, she was registered in the “paid” classes, presumably under scholarship from the parish, with the secret intention — and intention that would be clearly revealed many years later—of grooming and attempting to attract her little by little to monastic life.

FAMILY RUPTURE AND RECONCILIATION

This same year, 1961, when she was 6 years old, her father left to “buy tobacco” and never returned home. Unable to bear the suffocating ambience of post-war Jaén, and seeking refuge in alcohol, he fled as did many of his generation to Barcelona in search of a better life, abandoning his family.

Ángela, her brother and her mother then moved back to the home of her grandmother Pepa Ramón, on Santa Cruz street. The home was a single room in the first floor of a neighbour’s old house. The dwelling lacked running water and there was only one tap on a wash fountain on the common patio and one Turkish toilet that all the building’s residents shared.

Ángela’s mother Ascensión divided the room with a curtain, to create two spaces: her sewing workshop upon entering, and behind, the beds and small stove for cooking next to the room’s single window.

Ángela shared a bed with her grandmother Pepa and continued to do so until she went to Granada to study at age 17.

Six years later, in 1967, at age 12, Ángela, who had never left Jaén, took a memorable and urgent trip with her mother in train to Barcelona to pick up her sick father who had been checked into the hospital. Until then, they had had no news or contact with him since he left. After picking him up, they all three returned to Jaén.

The family, now back together, then lived with grandmother Pepa, in a flat on Merced Baja street, that Ascensión (Ángela’s mother) had bought not long before thanks to her savings, after the street-side wall of her bedroom in their previous house suddenly collapsed in the middle of the night.

NEW HOUSE AND LITERARY DISCOVERIES

In this new house which had previously been the residence of a priest, Ángela made a fantastic discovery. A pile of books turned up in a room that the neighbours had initially decided to burn, having deemed them useless, and besides, they were “a priest’s books”. When Ascensión caught wind of this she asked the neighbours to wait for her daughter “who likes books so much” to take a look at them before throwing them into the fire. Ángela arrived not long after and discovered among the pile two small books with red covers that read: Voltaire “The Bible Explained”. Reading this bibliographic gem would mark her forever.

Not long after, while living at this house, at 12 years of age, Ángela would discover Federico García Lorca, also by chance. Having written and recited a poem in class, the teacher reproached her and accused her of plagiarizing Federico. Ángela responded defiantly that those verses were hers and hers alone, and besides she had no idea who this Federico was. She thereafter discovered the work of the author who wrote “Romancero gitano” [The Gypsy Ballads] and became totally enamoured of his work and his person. Through Federico García Lorca, she would get into the work of the other authors of the Generation of ’27 such as Antonio Machado who would be an absolute point of reference for her throughout her life.

In 1970, three years after his return to Jaén, Ángela’s father Ángel, died suddenly of a heart attack at 42 years of age. It was around this time that her paternal family summoned all the “Argotes” from Jaén to inform them that after long and costly investigations, it had been confirmed that they are direct descendants of the legendary sixteenth century poet Luis de Góngora y Argote. Ángela was 15 at this time. She already studied at high school and had devoured all the poetry in the Spanish language that she could encounter. She couldn’t help but exclaim with the innocence and rebellion of youth: “Bearing in mind that Don Luis was a priest, it’s clear we’re all “hijos de p…!”.

POLITICAL AND MILITANT CONSCIOUSNESS

The following year, 1971, she focused on studying sciences at the high school in Jaén, where she excelled thanks to her outstanding scholarly record together with her tenacious spirit of rebellion. With the discrete support of a teacher that was one of Antonio Machado’s students in Úbeda, she was able to organize a few introductory workshops for her class on the subject of Marxism.

In 1973 after completing her high school studies and finishing her course of orientation for university, she finally was able to escape the asphyxiating ambience of Jaén, and would travel to Granada to study medicine. She would then immediately find herself in another world.

She quickly achieved contact with the militants of the Spanish Workers’ Party (PTE) and signed up to join the Youth Red Guard, a political formation that had Marxist, Leninist, and Maoist orientations. She would compliment her studies in medicine with clandestine militancy and the political agitation characteristic of those years, while reading literature by revolutionary authors such as Marx, Engels, Lenin, Ho Chi Minh, Mao, and many more.

GRANADA AND ITS POETS

She would frequent, as it couldn’t be any other way, the poetic circles of the city of Granada and meet Elena Martín Vivaldi, Rafael Guillén, Antonio Carvajal, Carlos Villarejo, Juan de Loxa, Luis García Montero and other poets of the generation known as “Poets of the South” although she would not ultimately share their path. Antonio Carvajal once told her she had two options as a poet: 1) To learn “the office” (i.e. to have a career) or 2) to live life. She chose the second and rejected the first without hesitation.

In these years she would eventually meet personally with Vicente Aleixandre thanks to the introduction of a French Hispanist at the university of Toulouse. This was an unforgettable experience for Ángela that would awaken in her a great admiration, never diminished, for the legendary Andalusian poet. Years later, she would say: “No one will be able to understand my work without first having assimilated that of Vicente Aleixandre”.

PRISON AND PSYCHOPHARMACOLOGY

In 1975, at age 20, she married a student of mathematics, a fellow member of the party and not long after was arrested for pamphleteering. All of her written work, all of her poetry, was also arrested and confiscated by the police and would disappear forever. Nothing remains of her work prior to 1975. She would spend seven days “incomunicada” locked up in the police station of the Albayzín, followed by a month in the prison of Granada.

After being released from prison with her husband, they travelled to her mother’s house in Jaén. The next day the Civil Guard was at her door to arrest and detain her again. This time they were looking for her due to her instigation of the Youth Red Guard chapter in Jaén with whom her brother Manuel was also a militant. Ángela would escape thanks to the astuteness of her grandmother Pepa, who hid her granddaughter in the bathroom that was next to the front door of the flat, and brought the Civil Guards into the living room at the end of the hall. There she kept them occupied while Ángela and her husband escaped carefully out the front door. They then fled on an old motorcycle to Cádiz, the home city of her husband.

There, her husband’s family, wealthy pharmacists originally from Extremadura, was “convinced” that the latest events to befall the young couple were due to the fact that Ángela was in need of psychiatric attention. To confront her condition of “fugitive of justice” they demanded she saw a psychiatrist and surrender herself to the police. Her husband approved of this strategy and would then confess that above all he wanted a “modern woman, but within the bounds of the classical”. Ángela gave in to their pressure, began a treatment with psycho-drugs, and surrendered herself to the police. She would then be locked up for an additional three months in the prison of Cádiz, where she would later experience from behind bars the widespread enthusiasm brought about by the death of Franco. Upon her release, she would begin to separate from her husband and renew her political activities, doing organizing work with women in the poor neighbourhood of La Viña de Cádiz. The leaders of her organization would then take notice of her as potential candidate to act as the “poster girl” for future elections with free access to the radical left.

HER BROTHER MANUEL, HER NEW LOVE, PARIS, CHANGES IN LIFE PATH

In 1978, Ángela had just turned 23 when her brother Manuel, who was 20 years old, was urgently checked into Puerta de Hierro clinic in Madrid, so he could undergo surgery on his heart. Ángela left it all, political activity and studies, to be together with her brother, with whom she would stay in the hospital during the following six months. Her decision would cost her being expelled from the party (for prioritizing family matters over the interests of “the cause”) and her experience of Spanish hospital protocol would end up leading her to abandon her studies in medicine: she would later quip “… I don’t want to be part of this pack of thieves and murderers”. On top of all that, at this time she separated definitively from her husband.

In November 1979, in a bar in the famous Plaza Nueva square, Granada, she would meet French cinematographer, Vincent Biarnès. After spending a Summer in Sweden in search of so-called social democracy, she had been studying psychology without much conviction. She had just recently completed her first book of poems: Momentos desde la soledad a un sueño. This book was composed of the only poems she had, fruits of the previous three years. At this point, she would begin a relationship that would last 34 years, until her death, in which her and Vincent’s lives would ever be closely intertwined. Again, she was about to encounter another new world: that of an artist in Paris.

In 1980 her brother Manuel died at 22 years of age. This would cause Ángela great emotional upheaval. She then moved to Paris, where she would live several years, visiting Granada all the while, as much as she could. In Paris, she lived surrounded by artists, musicians, painters, and performers. She would read the French originals of Baudelaire, Rimbaud, Apollinaire, Jean Cocteau, René Char, and deepen her knowledge of Voltaire, Sade, Victor Hugo, Antonin Artaud, and the Surrealists. She would also read Tagore, Descarte, Freud, Nietzchse and Sartre. This time was very prolific for her as a writer. She would write many books, including Made in Paris, and En un barco de piedra por los mares del cosmos [On a Stone Boat through the Seas of the Cosmos], this last inspired by the death of her brother. In this book she initiates a spiritual voyage, following her brother’s trail, dialoguing with him, traveling through the universe and the cosmos. Several years later, in the late 1980s, her magnum opus would emerge from the seed of this earlier book, an epic poem in three acts entitled El llanto de la Amarga o Las aventuras de Agreste a través de los mundos of which we will speak more shortly.

RETURN TO GRANADA, CREATION OF THE TALLER DE ARTE VIMAAMBI

In 1984, Ángela and Vincent would buy a house in the Albayzín neighbourhood. Their first son, Manuel, was born in 1990, and Ángel, their second, in 1992. In August of that same year they would open their Taller de Arte [art workshop], an association of artists, musicians, painters, poets, and cinematographers dedicated to promote and foment all kinds of artistic offerings, whether literature, plastic arts, music, or cinema.

This space was founded together with renowned Japanese painter Yasumasa Toshima; Miguel Lara Molina, an artist from Jaén; Joaquín Martínez Albarracín, a young engraver from Granada; and David Lenker, an American musician and jazz pianist.

To celebrate the opening of this “poet’s portal”, as Ángela liked to call the space, she published her first book, Distancia [Distance] screen printed by the author herself.

From then on, Ángela would develop an incessant activity: permanently reclaiming the dignity of all human beings, the importance of Art and the work of artists. From this Taller [workshop], that features a gallery and small performance space, she would work to achieve this goal, a goal that she believed was essential to her office as a poet, organizing art shows, poetry recitals with music and creating multimedia performances that blend music, poetry, plastic arts, and cinematography. In the year 2000 she would begin to work with young flamenco artists from the Albayzín neighbourhood and create a flamenco show entitled On a Stone Boat through the Seas of the Cosmos based on the still unpublished book of the same name.

In 2007, coinciding with the inauguration of the “concert hall” feature of the Taller, the “Sala Vimaambi”, she would create a show that is still offered each weekend from then on, Raíz y Duende [Root and Fairy], a vision conceived with the purpose of promoting new generations of flamenco artists in Granada.

In 2010, the Deputation of Granada would publish, as number 50 in their Genil de Literatura series, Ángela’s poetry collection entitled Made in Paris, illustrated by Granada painter and president of the Rodríguez Acosta Foundation, Miguel Rodríguez Acosta Carlström.

Death would visit Ángela suddenly, in the hours before dawn on September 4th, 2013. She left this world at 58 years of age.

***

Excerpt from “Ode to MAAM”

English translation

MAAM — for your tresses of cowry shells

your tresses of glowworms of wasted carnations

and for your ears demoniac angelic

and for the jellyfish of darkness the hurricanes you summon —

that purify Granada of the puss of oblivion —

and for your written words that dance upon the page

your written words that fall like stars

and swing on vines and hang like children in parks

for you who are an echo of great mother poetry

for you who are an andalusian sappho

adoring the reflection of the moon in the asphalt

by rhythms of martinete and fandango

— I write you this ode.

MAAM — do not forget you are loved

I give you honour in this life

so the critics feed not upon your blood ‘a título póstumo'

MAAM — the first time I heard your weeping gun

your tears hurled without aim

the molotov cocktail of your tender verses

something told me you would bleed open my veins and make them into roots

MAAM — your very name an invocation ringing in the caverns of the earth

MAAM — I have seen how the youth of the neighbourhood come to you for council

have seen how you speak with trees and wind

have seen how you walk with care among the pines

have seen how you call to the Moon

and the sharp petals of almond flowers tremble

in a light more silver fresh and shocking

than is possible

and I have seen those who emerge

your demoniac band

sirens skeletons

oh curses! oh desire most intimate!

lovely things that flash across the black mirror of being —

and I have seen the spectre that hovers about the Sala Vimaambi

with white hair and smile of luminous fool:

your dead friends who give warm winds to the borders of your wings

MAAM —

María of the Angels

María of the Lost Angels of the Albayzín

María of Divine Fools and Wine Fools

María of the Free and Secret Children

María of the Vimaambi

You need not unravel the enigmas

of the Sphinx of Andalucía

when you are her, you are her!

— a mask enfleshed in blueness profound

and for your man

Child of the Earth

fingers salty with mud

indomitable horse

adorned with red ribbons

with will of absolute pistol —

and locked in love’s dance

each other perpetually overwhelming

in nights full of snow

and for your sons — Vimaambi princes

the courtesy of Angelín’s well of spirit

the music that falls from Manolín’s fingers

MAAM — if you cry when these ripples brush your ears

remember you are loved by the living and the dead

I give you infinite blessings from my drunken lyre

for your soul

your soul of windblown seed

your soul of forest clearings

your soul of candles drowned in wine

your soul of diamond beaches and black seas

your soul of olive tree

your soul of swan and mountain spring

I sing you

your soul

and your voice

your voice of dark fairy

your voice of medusa and maritime monster

your voice of St. John bonfire

your voice of red herbs

your voice of mother tiger

your voice of hurricane

your voice of forgotten roses

your voice of the boulders of Jaén

your voice of the wind of the Albayzín

your demoniac voice clean voice

that warms blood

that shatters falsehood and inspires fear

in the shoulders and stomachs

of those unable to confront their mirror

voice of dangerous red haired girl

with visions and power beyond her years

voice that was inaugurated crying in the womb

oh voice that permits me such lyrical flight!

MAAM — when you die

if you had a gravestone

I would douse it with water and sugar

that the mouths of ants

wash you clean

I would bring blood drop carnations

that would change to scarlet butterflies

I would bring sweet herbs

and together we would smoke

and laugh and speak

on the lovely nonsense

of the human condition

and then when I die

my own voice my voice of satyr

my voice of cold arrow my smooth and wicked voice

my voice of blood and limestone

would join with yours

yours that will ever be roaring over the mediterranean

— inevitably —

yet not by rhythms of bulería nor by those of soleá

but by the flamenco rhythms

of our selfsame souls.

SLIPPERY ELM

Slippery Elm is a poet and the author of The Dead Hermes Epistolary (Gods&Radicals Press 2019), a work of anti-fascist philology that examines the relationship between language and the land, the connections between capitalism, cultural erasure, language loss, and ecocide, and which also includes a practical epistle that weds permaculture design with the traditional methods of medieval Islamic agriculture and husbandry, written in the interest of empowering revolutionaries. A long time permaculture designer and guerrilla gardener since completing a two-week training taught by Starhawk while still a beardless youth, his passions for food sovereignty and food security have led him to work in high mountain olive groves and agro-ecosystems, as well as hay fields in desert climes and in intensive market gardens in temperate rainforests. He is a father, a student of martial arts (Krav Maga, Irish stick), and believes the methods of permaculture to be a powerful means of bringing about a conquest of bread.