Paganism within the Project of Equity

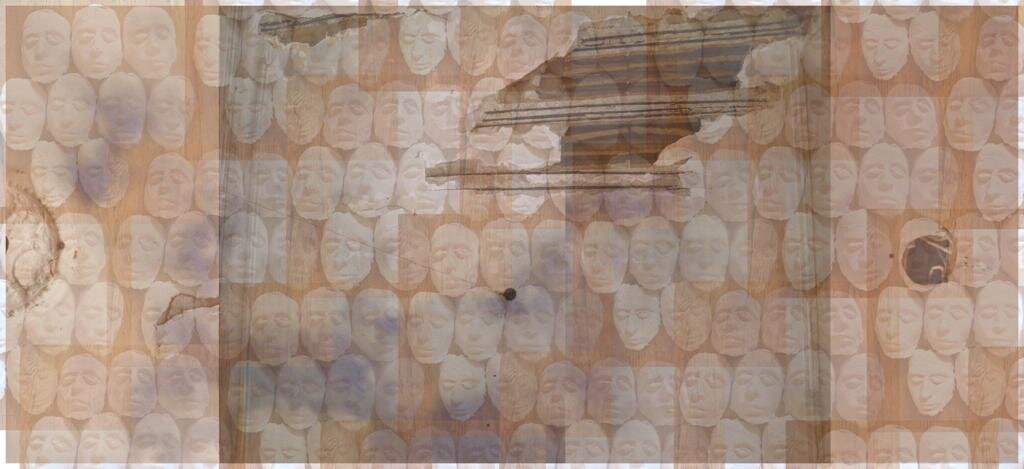

Glass Ceiling, photograph of handmade paper castings superimposed on images of ceilings from a trip to Havana, Cuba. Li Pallas, 2013.

“Intimacy is a critical feature of this coerced labor and of care. Black intimacy has been shaped by the anomalous social formation produced by slavery, by involuntary servitude, by capitalist extraction, and by antiblackness and yet exceeds these conditions. The intimate realm is an extension of the social world—it is inseparable from the social world—so to create other networks of love and affiliation, to nurture a promiscuous sociality vast enough to embrace strangers, is to be involved in the work of challenging and remaking the terms of sociality.”

(Saidiya Hartman)

Elections have the habit of making even the most radical among us elevate the project of democracy. If the United States were a true democracy, that would be a vast improvement over the present condition. But what this line of thinking fundamentally does is provide a simulacrum of arguments for equity. In this way, equity shifts gently away from what it would be in earnest, and all arguments about equity become about democracy.

Questions around an equitable democracy inevitably revolve around pluralism. Let’s remind ourselves that plurality has two meanings which are slightly different. One is a voice for everyone included. That’s a nice ideal, and one that is perhaps better than what is reflected in our present condition. The second, somewhat derived from the first, is the largest group. One suggested fix for certain elements of democracy in the United States would be to shift away from a mere plurality of votes to requiring a majority win; or shifting away from a representative democracy to a total democracy — embracing a more pluralist project. These are good first steps.

In paganism, people like to suggest that polytheism is itself an embracing of pluralism, and that this makes it closer to the project of equity. It inverts Hegel’s claim that only monotheistic people can imagine freedom, and so slavery is not wrong, since polytheistic people are incapable of true freedom. I would argue that both are mistaken as to what the project of equity is. No point of view is automatically equitable, equity is something that requires constant reinvention.

From my former post as print designer at Gods and Radicals, I’ve grown persistently wary of how racial equity is characterized within the press. Saidiya Hartman, Safiya Umoja Nobel, and Zakiyyah Iman Jackson are three of the biggest names in Black leftist writing right now. Along with Denise Ferreira da Silva, Ruha Benjamin, Barbara Smith, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, or even Aimé Césaire; these names are woefully absent.

At the Gods and Radicals website, Mirna Wabi-Sabi and Angie Speaks contribute poignant criticism and are wonderful additions to the G&R cannon, but pointing to them while excusing the rest isn't progress — it's tokenism. Deepening a bench of citations to include names like these would mean embracing a more pluralistic approach. To do so, we have to become a lot more comfortable discussing identity — not less.

As the United States has met one of the largest reckonings with its own racist history and its people increasingly aware of contemporary Black scholarship, what are the mechanisms preventing the inclusion of these names? What do these scholars have to share with us?

In an essay within the anthology Racism Postrace, Safiya Umoja Nobel and Sarah Roberts define postracialism by quoting legal scholar Sumi Cho, saying it is an “ideology that reflects a belief that due to the significant racial progress that has been made, the state need not engage in race-based decision-making or adopt race-based remedies, and that civil society should eschew race as a central organizing principle of social action.” Cho adds, “post-racialism as an ideology serves to reinstate an unchallenged white normativity.”

Saidiya Hartman writes about the abolition of whiteness in Art Forum — which is different from the previous understanding of postracialism, and so deserves clarification. In bold letters she says “it requires a radical divestment in the project of whiteness and a redistribution of wealth and resources. It requires abolition, the abolition of the carceral world, the abolition of capitalism.” She says, “There’s a great disparity between what’s being articulated by this radical feminist queer trans Black movement and the language of party politics,” and what she calls for is a movement steeped in liberation from the politics of vulnerability and violence — itself drawing from the work of the Combahee River Collective and the original intent of Identity Politics. She ends the piece by naming many of the scholars I’ve highlighted above.

Media Receiver, photograph 2 of 4, an experiment in noise reduction with paper castings from shredded newsprint. Li Pallas, 2012.

Hartman is also the author of a magnificent work called Scenes of Subjection in which she argues that empathy across power differentials is a kind of violence by demanding vulnerability. Humanists have long called for empathy and humanity of “others” in order to move to points of equity, and again, this sounds good in theory. What this ignores, as Zakiyyah Iman Jackson points out in her recent book Becoming Human, is that Blackened people are not thought of as subhuman; they are imagined as superhuman, human, and subhuman simultaneously. White Paganism has a lot to atone for in the ways it participates in this process through magical tokenism or goddess worship. Harm is too often justified by resilience to it.

If we believe in Fascism as Aimé Césaire contextualized it — not just as authoritarianism — but as Eurocentric white violence turning in on itself; then a Paganism which is against fascism should be constantly fighting against racism. White Paganism has a special place within the history of fascism, let us not forget since, that is why Gods and Radicals has been accused of cryptofascism. Nazis old and new have repeatedly turned to paganism for symbols to reify their concept of white nationalism. It’s normal to be somewhat unaware of this tendency, and instead turn to the church to blame it for hardening authoritarianism.

I was not aware, at the time of designing the cover for True to the Earth, of the group Identity Evropa. I can’t help but think they would have a very different interpretation of Europa holding open the mouth of the Wall Street Bull, and celebrate it. Complicating the matter is that the alt-right is pushing to deliberately create a terrain of obscurity in which hegemony can thrive.

TRUE TO THE EARTH, cover. Book available here.

Moving from hegemony to equity is a process of constant renewal; it is a form of abolition. Abolition does not mean rejection, it means a process of systematically undoing forms of harm by replacing them with systems of care. Noam Chomsky reminds us that, “at every stage of history our concern must be to dismantle those forms of authority and oppression that survive from an era when they might have been justified in terms of the need for security or survival or economic development, but that now contribute to — rather than alleviate — material and cultural deficit.”

Christianity was once that authority but, as McKenzie Wark wrote, “Karl [Marx] has to part ways with those who are still caught up in the task of the critique of the old ruling class and it’s ideology — religion” (Capitalism is Dead, 2019, pg 166). She later reminds us that Proudhon and Weitling, while not emblematic of their time, are rooted in Christian appeals to justice — though she is an atheist. As we reject Christian forms of purity and Western dualism, we must not let our rejection be so totalizing as to obfuscate dreaming of a society brilliantly committed to harm reduction.

Coming back to the question of equity as harm reduction, is pluralism always equitable? Let’s suggest that the whole City of Los Angeles votes on turning a poor Black neighborhood into a repository for toxic waste. This is purely hypothetical and not typically how such decisions are made. The goodness of humanity might prevail, but let’s say, for argument’s sake, that the majority of people in Los Angeles, who aren’t Black, recognize that they do not want the waste in their own neighborhood, and vote for this new repository. Is that equity? And if not, what is?

Equity might mean that, as artist/urbanist and Black feminist scholar Romi Morrison said in an interview with me this summer, “you have to take your rightful share of the toxic.” Responding to a question on horizontality, Morrison questioned whether or not horizontality was even equitable because of the historicity of it. It is not equitable to simply evenly distribute toxicity, if, over time, that distribution has been unevenly distributed. I’d like for our community to sit with this, as we think about what an equitable press might look like. What steps beyond pluralism could the press take?

The recent infusion of toxicity on the United States Supreme Court, for example, caused many to discuss the prospect of court packing — equity as democracy as pluralism. I’m much fonder of term limits. Term limits, while also not a perfect fix, do much more to diversify leadership by repeatedly seeking out new and different leadership. They are different from canceling, because, for example, if a Supreme Court Justice’s term is up they could still serve on lower courts.

There is a joke at academia about how to deal with the fact that too many tenured teachers are white men: early retirement. No one’s saying you should stop writing, or stop researching, but it might be time for certain people to rest their pens a little to open up the lines of power and resources to a fresh group of people. One should not use austerity to reinforce the status quo.

How might we reimagine accountability, including its historicity, without divulging into a kind of violence itself? How do we, as Ruth Wilson Gilmore suggests, rebuild a society based on care? Canceling is not the answer, in part because the process of canceling too often favors hegemony itself — canceling often silences the people who are calling out oppression rather than those who are committing it, however accidentally.

Moving towards democracy is a good first step in the process of remaking our community, and I certainly hope this happens. I am, perhaps, more excited for the steps it chooses to make beyond that, in the project of equity.

Li Pallas

(they/them) is a Designer, Filmmaker, and Urbanist living in Los Angeles, CA whose critical practice is one of repeatedly examining discourse for false dualities in order to illuminate who benefits from generalized obscurity. As such, they center their politics on how the intersections of transness, BIPOCs, and abledness illuminate pathways for collective liberation, rather than individualized upward mobility. Their current film project takes this perspective while trying to get back to something of “worldview.”