The Wizard & the Prophet ... and the Microbiologist?: 3 Visions of Our Future

A futuristic vision of farming (Arthur Radebaugh, public domain)

It’s April 1946, and two men are standing on the edge of a field of dying wheat on the outskirts of Mexico City. They are looking at the same field, but they see two very different visions. Both look at a field stricken by stem rust, a condition largely unknown today, but which was responsible for millennia of famine and untold human deaths. One of them sees the potential to grow a strain of wheat resistant to stem rust, and thereby to feed billions. The other sees the need to drastically reduce the human population to within the carrying capacity of the planet.

The two men are Norman Borlaug and William Vogt, and they are, respectively, the Wizard and the Prophet in the title of Charles Mann’s 2018 book, The Wizard and the Prophet: Two Remarkable Scientists and Their Dueling Visions to Shape Tomorrow’s World. Mann presents Borlaug and Vogt as archetypes, representatives of two different visions of humankind’s relationship with the natural world: the one viewing nature as a something to be bent to the will of humankind, the other viewing nature as something to which humankind must bend.

“Vogt saw the land behind and beneath as the protagonist of the story—the origin of both problem and solution. With his ecologist’s eye, he viewed the fundamental issue as one of carrying capacity. People, biological agents like any other, had to fit in. By contrast, Borlaug saw the farmers as the central characters. Their suffering was caused not by overshooting the capacity of the land but by their lack of tools and knowledge. With industrial fertilizer, advanced irrigation techniques, and the finest new seed stock, they could transform the landscape, making it more productive and themselves wealthy. Fitting in with their world would be a human catastrophe. Instead they needed to reconstruct that world on more useful principles.”

The Wizard

Norman Borlaug was the Nobel Peace Prize-winning father of the “Green Revolution” and is credited by some people with saving a billion people from starvation. Other people blame him for the deaths of millions and immeasurable ecological devastation.

Norman Borlaug, the “Wizard”

In the mid-20th century, Borlaug conducted agricultural research on behalf of the Rockefeller Foundation in Mexico. He succeeded in developing a hardy, disease-resistant, high-yield variety of wheat, which when combined with other modern agricultural techniques nearly doubled crop yields. Borlaug’s seed was sent to famine-stricken areas of the globe, including India, Pakistan, Asia and Africa.

It is hard to overstate the revolutionary nature of what Borlaug accomplished. He seemed to have almost broken the bond between food and the earth. He bred a strain of wheat that could be grown anywhere, regardless of the local conditions. As long as farmers added the right amount of water and fertilizer, the grain would grow, and in greater quantities than ever before seen.

“The package was a turnkey, ready for use. Switch it on, and yields would skyrocket. No longer did farmers have to worry much about local varieties or particular soil conditions or (if they had irrigation) even the weather. Just follow the instructions, same here as anywhere else; the package was good for everyone. It freed farmers from the land …”

All of this was happening at the same time biologist Paul Ehrlich was writing his 1968 bestseller, The Population Bomb, in which he predicted hundreds of millions of deaths in India from starvation. And Ehrlich would have been right, if not for Borlaug’s Green Revolution.

But there was a dark side to the Green Revolution, which led to the the spread of large-scale, industrial, monoculture farming. The modified strains of wheat (and later rice) were highly “input dependent”, meaning they would only outperform traditional varieties when combined with modern irrigation systems, non-renewable fertilizers, and chemical pesticides. These “inputs” have wreaked havoc on ecosystems around the world. What’s more, while the grain yields have gone up, the efficiency of the food production system has gone down, meaning that the amount of energy required to produce the same amount of grain has actually increased! Industrial agriculture is one of the biggest contributors to climate change today.

There have been social costs as well. The Green Revolution has yielded big profits for agribusiness and chemical companies, but widened the inequality gap for the world’s poor. It undermined socialist land reform movements and increased farmer debt and unemployment. And, in some instances, the Green Revolution actually resulted in less food, where land previously dedicated to subsistence farming was redirected toward growing grain for export or for animal feed, or less nutritious food, where polyculture farming was replaced by monoculture grain crops.

Mann explains that these are the unavoidable outcomes of a reductionist approach to nature which was typified by Borlaug:

“Farmers in India and Mexico thought of their wheat in terms of how they experienced it—as a plant that was (or wasn’t) easy to grow and harvest, as grain that made flour with certain qualities, as the source of bread that, eaten daily, conveyed a statement about their lives, as a set of smells and tastes and colors, as a storehouse of memory and identity. Borlaug had taken this wheat into the workshop of science. There, in effect, he reduced wheat to a series of numbers: plant height, degree of rust resistance, spikelet number, flowering date, and so on. He measured these numbers in an effort to maximize another number: the weight of harvestable wheat. All of this was totally normal scientific procedure. And it worked—he created varieties of wheat that were resistant to multiple types of rust and yielded two or three times more grain. But what was left out was the color of the bran, the texture of the grain, the pleasure of having several different types of flour, or, more important still, the relationship of the farmers to their land, and to each other, and the structure of power in a community or a nation.”

The Prophet

From the perspective of the Mann’s titular Prophet, William Vogt, the fundamental problem with the Green Revolution and other “Wizardly” projects like it was that they failed to respect natural limits. According to Vogt, masses of hungry people was not a problem of crop yields, but of overpopulation and overconsumption.

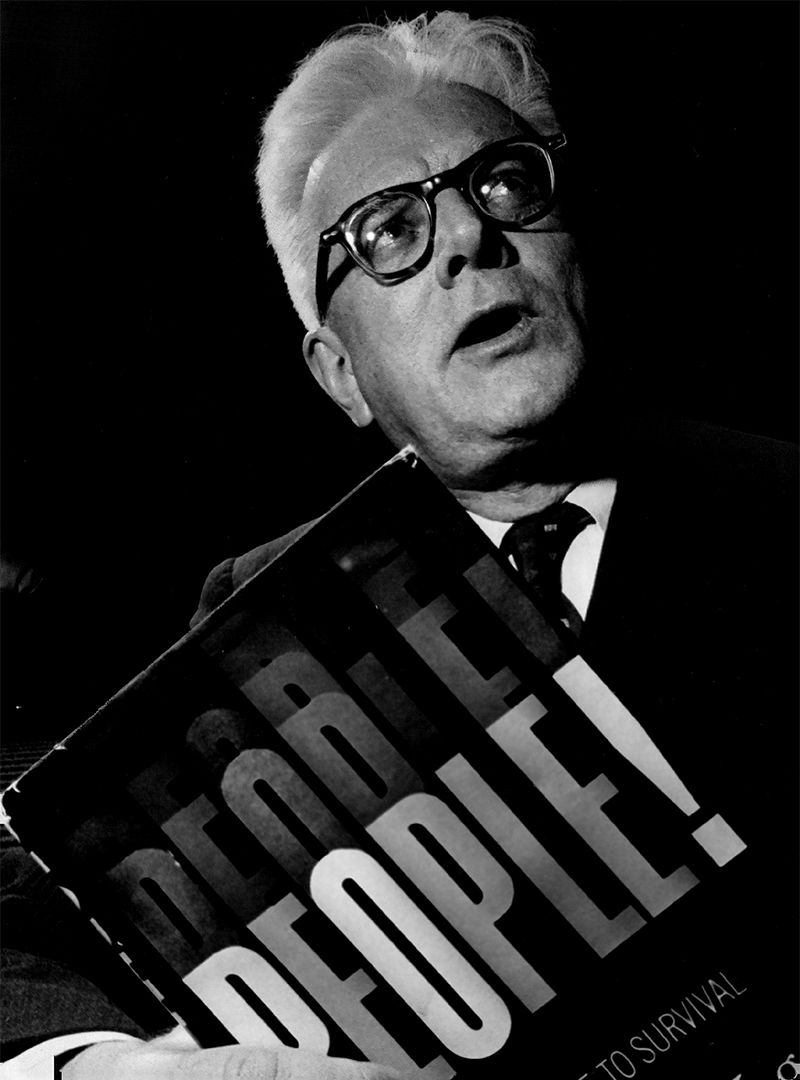

William Vogt, the “Prophet”

Before his visit to Borlaug’s wheat field in Mexico, William Vogt studied bird populations. Like Rachel Carson, a generation later, Vogt came to believe that declining bird populations were being caused by habitat loss from suburbanization and by concomitant chemical mosquito control.

Vogt was eventually fired from the Audubon Society because of his crusade against mosquito control, which is why he took a job studying seabirds off the coast of Peru. The islands of Peru’s coast were notable for the accumulation of bird guano, in some places as high as 150 feet. The guano was an excellent fertilizer, and so it was a significant source of income for Peru. But when bird numbers started to decline, Vogt was hired to find out why.

Vogt discovered the the bird decline was being caused by the El Niños, the natural cyclical periods of warm ocean water. The Peruvian government wanted Vogt to tell them what to do to fix it. Vogt’s answer: Nothing.

Yes, during the El Niños, the birds left their nesting grounds and didn’t have offspring, which reduced their population and thus their guano output. But these losses, he said, were not actually a problem; they were natural changes—a safety valve—without which the bird population would grow unchecked until it had consumed all the food in the area, which would eventually cause population collapse.

What Vogt took away from this was a lesson about the importance of respecting natural limits. As he explained in a 1945 article in the Saturday Evening Post, humankind, though “apt to forget it, is a creature of the earth. ‘Dust thou art’ and ‘All flesh is grass’ were not said by scientists, but they are sound biology.”

In 1948, Vogt published the best-selling book, Road to Survival, which has been credited by historians with introducing the idea of “the environment” to the masses. According to Mann, Road to Survival was the first book to portray our many and seemingly discrete environmental problems as a single, interconnected “Earth-sized problem” caused by capitalist consumption and unchecked human reproduction. The book would eventually inspire Rachel Carson, the mother of the environmental movement and author of Silent Spring, as well as Paul Ehrlich, author of The Population Bomb. True to his vision of humankind living within natural limits, Vogt went on to become the national director of Planned Parenthood and secretary of the Conservation Foundation.

Mann uses Borlaug and Vogt as archetypes of two different visions of humanity’s relationship with nature. The Prophets are apolocalypticists. In their view, humankind will face an extinction unless we drastically reduce our consumption. Rather than being our salvation, affluence is our bane. The Wizards, by contrast, are techno-optimists. They believe that, when properly applied, science and technology will enable us to produce our way out of any predicament. Affluence, in this view, is not the problem, but the solution.

“Prophets look at the world as finite, and people as constrained by their environment. Wizards see possibilities as inexhaustible, and humans as wily managers of the planet. One views growth and development as the lot and blessing of our species; others regard stability and preservation as our future and our goal. Wizards regard Earth as a toolbox, its contents freely available for use; Prophets think of the natural world as embodying an overarching order that should not casually be disturbed.”

It should be noted that the Wizard-Prophet divide is not a question of science versus anti-science. Both sides have science on their side—albeit two different models of science. The Wizards speak the language of reductionist positivism, which proceeds by breaking systems into their smallest parts and reorganizing them for human benefit. The Prophets also speak the language of science, but the more holistic science of ecology, which strives to understand the place of everything within natural systems. The Prophets seek to discover boundaries and limitations, so they may be respected. The Wizards see natural limits as challenges to be overcome.

Earth

Mann explores the Wizard-Prophet divide in the context of four areas which he relates to the Aristotelean elements: food (earth), freshwater (water), energy (fire), and climate (air).

In the area of food production, Mann’s examples of the Wizard archetype include Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch, who discovered the key to making synthetic fertilizer. The Haber-Bosch process, as it is called, is one of the most important technological developments in human history. It has enabled human beings to extract enough food from the same amount of land to feed an additional 3 billion people, but it has also literally changed the chemical composition of the earth, as well as our atmosphere and oceans. Almost half of the fertilizers applied to the soil have washed into rivers, lakes, and oceans, where it creates algae blooms and ecological dead zones.

Land Institute researcher, Jerry Glover, holding an example of kernza, a perennial wheatgrass plant. Compare the root network of the perennial plants (left) to that of traditional bread wheat (right).

Mann’s examples of the Prophet archetype in the area of food production include Robert McCarrison, the founder of the organic movement. Rather than seeing the soil as a passive reservoir of chemical nutrients, McCarrison saw it as a complex, living system. And rather than trying to replicate that system in a laboratory, McCarrison believed we simply need to let the soil ecosystem do what it does naturally—by returning plant remains and animal excrement to the soil. “The slow poisoning of the life of the soil by artificial manures,” wrote McCarrison, “is one of the greatest calamities which has befallen agriculture and mankind.” When humans forget their relationship to the soil, he believed, civilizations fall.

The Wizards see the harms caused by industrial agriculture to be temporary technical problems, glitches, to be solved with more technology. The Prophets see the harms caused by industrial agriculture, not as a bug, but as a feature of the system, a system which refuses to respect natural limits. Giving people better technology just causes them to hit the limits of nature faster.

Whatever the downsides to industrial agriculture, Wizards respond, is it really better to let millions die of starvation? The Prophets see this argument as tautological, because it fails to address the underlying question of why there are millions of people starving in the first place: the failure to constrain human consumption and reproduction.

To the Wizards, it’s simply a question of numbers: numbers of humans and numbers of calories. To the Prophets, evaluating agriculture in terms of calories produced is reductive thinking. It doesn’t include the costs of habitat loss, soil erosion, or the poisoning of soil and water with pesticides and herbicides. What’s more, it doesn’t consider the destruction of rural communities. It doesn’t even consider whether the food produced is nutritious or whether it tastes good.

Both sides admit that organic farming will not feed the almost 8 billion people on the planet now (not to mention the 10 billion who will inhabit the earth in 2050). The Wizards see industrial agriculture and GMOs as the only solution. The Prophets see this as adding to the problem. The only real solution, according to the Prophets, is a top-to-bottom reordering of society along the principles of “less is more” and “small is beautiful”.

The Wizards accuse the Prophets of being elitists, ignoring the poor, and even racist. The Prophets accuse the Wizards of being tools of an economic system which is fundamentally at odds with the ability to sustain life on Earth, and in some cases, consciously complicit with corporate capitalists.

Mann notes that, on their own terms, both views are right. But they are irreconcilable, because they are based on two radically different visions of the relationship between humans and the earth:

“To Borlaugians, farming is a species of useful drudgery that should be eased and reduced as much as possible to maximize individual liberty. Borlaug’s life is an example: when his family mechanized their farm by buying a tractor, it freed him to go to school, and from there to change the world. …

“To Vogtians, by contrast, agriculture is about maintaining a set of communities, ecological and human, which have cradled human life [since the beginning of civilization] ten-thousand years ago. It can be drudgery, but it is also work that reinforces the human connection to the earth.”

Water, Fire, Air

In the area of freshwater, the Wizardly or “hard” path is supply-focused. It is the path of centralized, top-down planning, huge concrete structures, and massive construction projects which reshape the topography of the earth. This path has succeeded in providing clean water for drinking and irrigation for billions of people. But it has also drained lakes, rivers, and aquifers and devastated entire ecosystems. The Prophetic or “soft” path, in contrast, is demand-focused. It is the path of decentralization, improved efficiency, and education. The Wizard asks, “How can we get more water to more people?” The Prophet asks, “Why are we using water to do this anyway?”

At its heart, these two paths pose the question of the place of human beings in relation to nature.

“Hard-path supporters see technology placing humanity in charge: we can move H2O molecules wherever we want to satisfy our wishes. Soft-path people think this level of control is illusory—cooperation and adjustment, not command and control, is the way to live. …

“One values a kind of liberty; the other, a kind of community. One sees nature instrumentally, as a set of raw materials freely available for use; the other believes each ecosystem has an inner integrity and meaning that should be preserved, even if it constrains human actions. The choices lead to radically different pictures of how to live.”

The same divide can be seen in arguments about energy. It’s not just a question of non-renewable energy sources (coal, oil, natural gas, uranium) versus renewable ones (sunlight, wind, geothermal heat). As Mann points out, those who are building giant, centralized solar facilities are Wizards, not Prophets; they are “hard-path advocates in solar guise”.

“The hard path … consists of distributing ever-increasing amounts of energy from big, integrated facilities: giant power plants, giant pipelines, giant tankers. All are massive, brittle, and ecologically destructive; all require control from repressive, technocratic bureaucracies. The soft path, by contrast, consists of bottom-up power generation from networks of renewable sources. It is small-scale, flexible, and respectful of environmental limits; it fosters community control and democracy.”

It’s no coincidence that the path which we have taken thus far is the path which allows wealth and power to accumulate in the hands of an elite few.

Will we scorch the sky?

In the area of climate change, the divide between the Prophets and Wizards is most stark around the issue of “geoengineering”. One example of geoengineering is the plan to pump sulfate aerosols into the atmosphere to reflect some of the sunlight reaching the Earth back into space.

“Geoengineering fights climate change with more climate change. … It replaces the idea of staying within natural limits with the goal of creating a balance on terms set by humankind. It is an audacious promise to fix the sky. It is one of the logical endpoints of the Wizards’ dream of human empowerment and grandeur.”

Many Prophets view climate change as the quintessential example of ignoring natural limits and geoengineering as human hubris taken to the extreme. Even if it were feasible, say the Prophets, geoengineering takes us further down the path to disaster by distracting us from the needed social and economic reforms.

The Microbiologist/Fatalist

In his introduction and conclusion, Mann presents a third perspective, one which challenges both the Prophet and the Wizard. Mann doesn’t give a name to this archetype, which I will call the “Fatalist”, but its representative is Lynn Margulis.

Margulis was one of the most important biologists of all time. She discovered that symbiosis lay at the heart of the evolution of complex life. Eons ago, independent bacteria merged together to form critical parts of plant and animal cells: chloroplasts and mitochondria. Margulis was also the co-developer of the Gaia Hypothesis, together with James Lovelock. And she is credited with expanding the scientific conception of the tree of life, from two branches (plants and animals) to six (plants, animals, fungi, protists, and two types of bacteria). Perhaps more than any other scientist, Margulis has expanded our knowledge of the complexity and interconnectedness of life.

So, was Margulis a Wizard or a Prophet? She acknowledged that human beings have been a successful species. But, she said, it is the fate of every successful species to wipe itself out. In Margulis’ view, both Borlaug and Vogt were wrong. Nothing is going to save us. Not technology. And not conservation.

Lynn Margulis

In Margulis’ view, we are like bacteria in a petri dish. Through chance or cleverness, we have grown at a phenomenal rate, wiping our competitors, overwhelming our environment, consuming everything in sight. But we are now hitting the edge of the petri dish. And like bacteria which have consumed all of the agar in the dish, we will starve and drown in our own waste.

Human beings are going through the same process as cyanobacteria did during the Great Oxygenation Event 2 1/2 billion years ago—only in reverse. Cyanobacteria were single-celled organisms who consumed carbon dioxide, which was plentiful in the atmosphere at the time, and excreted oxygen. They were so successful as a species and they multiplied to such a degree that they actually changed the composition of the atmosphere…and suffocated themselves as a result.

Now, we’re doing the same thing, by billing the atmosphere with our carbon waste. It’s truly humbling to think that, despite billions of years of evolution, we are making the same mistake as our bacterial ancestors.

As Margulis sees it, the essential question is whether human beings are special, whether we are different from all the other species on the planet. Borlaug saw that human beings as special because he believed we can transcend the limitations of nature. Vogt believed we are special because he hoped we could learn to live within the limits of nature. Margulis would have said both of them are wrong.

Who’s Right?

Where does Mann come out on the Wizard-Prophet debate? He describes himself as a Prophet who converted to a Wizard, but now that he has children, he find himself waffling. His ambivalence is evident in The Wizard and the Prophet, where he oscillates between the two positions.

But I think the really interesting question he raises is not whether Borlaug or Vogt were right, but whether Margulis was right. She believed that human beings are not special, and we are fated to hit an evolutionary brick wall. (It would make sense of the Fermi Paradox, why the earth hasn’t been visited by intelligent extraterrestrials.) Mann offers no evidence that Margulis is wrong, nothing more than hope. But I have to wonder, is hope really anything more than hubris?

For my part, I started out as a Wizard, and then converted to a Prophet—around the same time I discovered Paganism. I suspect that most Pagans and most people reading this will identify with Prophets as well. (There are some people in the Naturalistic Pagan community whose faith in science resembles the optimism of the Wizards though.) But, recently, I’ve come to feel more like a Fatalist, through perhaps a Fatalist with an asterisk.

More and more, I find myself agreeing with Margulis. I think we are doomed, both as a civilization and as a species. But if that’s the case, what are we to do with ourselves? If both Borlaug and Vogt are wrong, if neither the hard path of the Wizards nor the soft path of the Prophets will save us, how will we be saved?

I’m starting to think that maybe what we need to do is stop trying to save ourselves. Maybe the effort to save ourselves is what has been keeping us from making the right choice all along. While individuals and small groups of people have chosen the soft path and followed the Prophets, as a whole, human civilization seems to have been following the hard path of the Wizards, at least since the Industrial Revolution, if not before. Maybe it’s the ultimate hope of saving ourselves, the dream of immortality, which has kept us on that path. If we stop trying to save our own lives and the creations of our own hands, maybe for the first time we could choose the right path.

If self-awareness is what makes human beings special, then I wonder if, paradoxically, our apotheosis will be when we become fully aware of the fact that we are not special, that after all we are dust and all flesh is grass.

JOHN HALSTEAD

John Halstead is a native of the southern Laurentian bioregion and lives in Northwest Indiana, near Chicago. He is one of the founders of 350 Indiana-Calumet, which works to organize resistance to the fossil fuel industry in the Region. John was the principal facilitator of “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment”. He strives to live up to the challenge posed by the statement through his writing and activism. John has written for numerous online platforms, including Patheos, Huffington Post, PrayWithYourFeet.org, Gods & Radicals, and now A Beautiful Resistance. He is Editor-at-Large of HumanisticPaganism.com. John also edited the anthology, Godless Paganism: Voices of Non-Theistic Pagans. He is also a Shaper of the Earthseed community which can be found at GodisChange.org.