The Witch-As-Body: A Review of The Brazen Vessel

“what springs forth from this erotic collaboration is a book I suspect generations of rebels will recognize as a powerful ritual of initiation.”

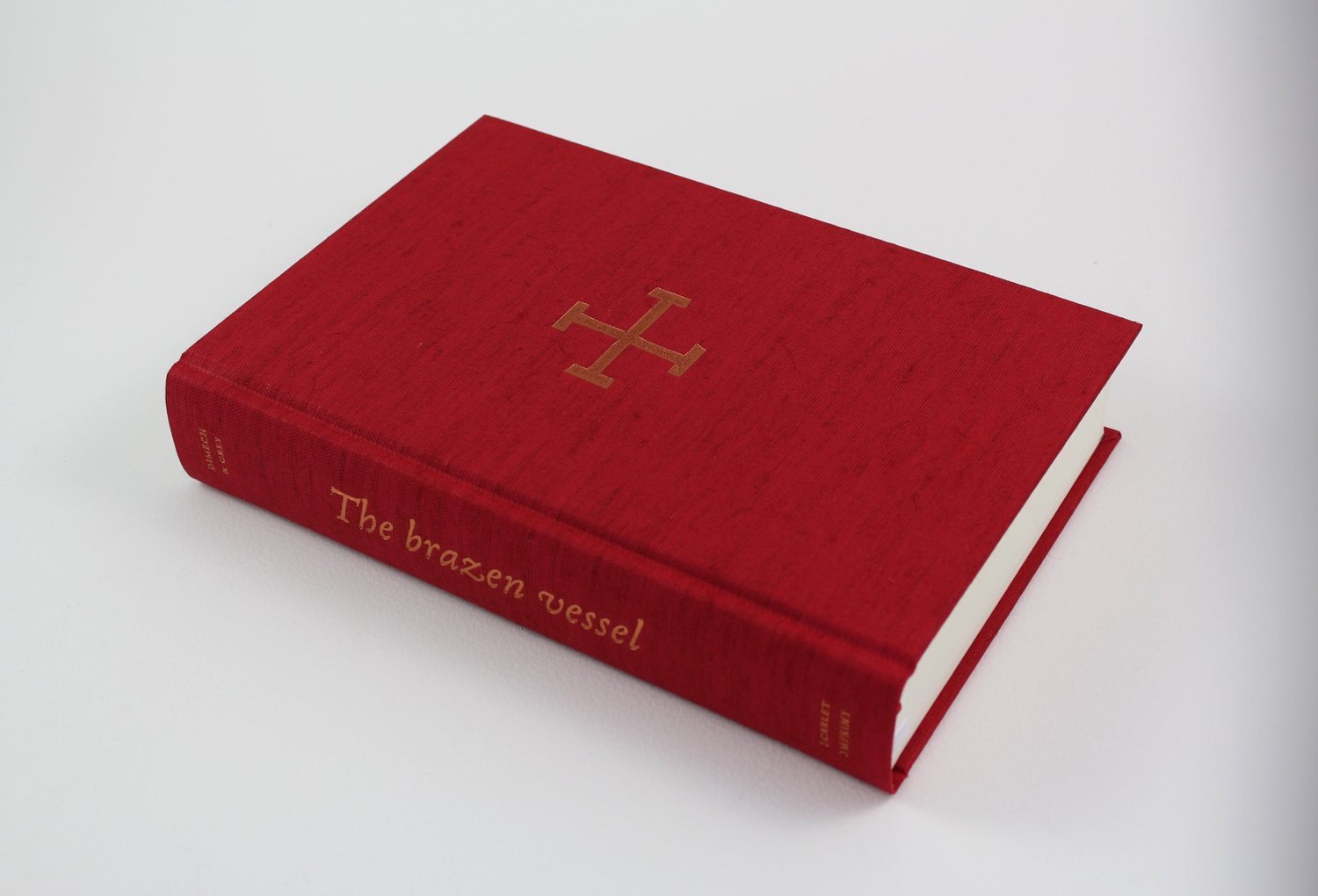

Reviewed in this essay: The Brazen Vessel, by Alkistis Dimech and Peter Grey

Scarlet Imprint, 2019; 432p

It isn’t easy to review occult works. Even more so than academic material, there’s a sort of credentialed posturing one is both tempted and expected to perform. It’s as if you need prove yourself worthy of reviewing the work, proffering subtle signs you’ve attained certain initiations or grasped specific mysteries lest you be known to all the world as a fraud.

This is because occult works, again like academic material, are usually bullshit. Not complete bullshit, mind you—there’s often some bits of profound wisdom to be gleaned from all the obscurantist babble. Gleaned, I say again, which is what the poor did after a field’s been harvested: they gleaned what remained after all the marketable stuff was carted away, processed, and consumed.

Whether its mid-century British occult works or post-modern critical theory, gleaning is usually a better route to actually finding something useful and revolutionary. This is not a false comparison: both genres of writing suffer from identical delusions that clunky and specialized words can replace concise thought, wagering that readers will be so dazzled with their own inability to understand the text that they’ll find it profound.

So let’s be clear: the obscure is not the occult, it’s just the obscure. Also, most academic writing is garbage.

Nevertheless, there’s still something that attracts us to archaic language, and complex thought cannot be reduced to an internet meme. Writing which feels too simple often is, and the stripped-down language of a pulp Llewellyn book or anything Jordan Peterson’s written yields no more profundity than a supermarket circular or a highway billboard.

This latter problem, I suspect, is an effect of the capitalization of language, the hegemonic processing of everything humans might say into market imperative. Just as the British Empire forced changes in the languages of the people it conquered (where it didn’t annihilate those languages completely) in order to make those speakers better consumers and workers, publishers, television, and radio media strip meanings from words in order to assemble them better as products.

These two tendencies create a frustrating dichotomy: we can have unreadable books or worthless books, incomprehensible theories or useless ones. Fortunately a few (and never mass-marketed) writers manage to escape this bind, as the writers associated with the Midnight Notes Collective (especially Silvia Federici) or Ellen Meiksins Wood have done with Marxism, or as bell hooks did for Feminism, creating works that neither coddle nor punish their readers while conveying deeply transformative ideas.

For the occult, only one publisher has managed consistently to strike this same balance. That publisher is Scarlet Imprint, run by Alkistis Dimech and Peter Grey. The books they create each manifest an undeniable commitment to language and thought both profound and beautifully readable. And thus it should be no surprise that their own writing bears this commitment, as seen startlingly in their long-awaited collection of essays—The Brazen Vessel—which is the subject of this review.

In reviewing works, it’s considered at least polite to the reader to disclose any relationship the reviewer has to the author, lest they be led astray by false assumptions of impartiality (as if such a thing really exists). So here’s my confession: I’ve cavorted with the devils. I’ve sipped green tea in wool socks while watching UFC fights with the two of them. I have helped Peter extract a lamb Alkistis found trapped beneath a wood pile, and smiled as Alkistis ordered Peter to pull over on the side of the road so she could feed an apple to horses. I’ve picked my way along the rocky cliffs of the Cornish coast in a rain storm alongside them, and I confess I’ve severely taxed their otherwise copious supply of coffee more than once. And I’ve watched the two jostle each other in their kitchen the way only severely-in-love people seem to know to do, and wondered in awe that brilliant people can be so wonderfully gods-damned human.

Alkistis and Peter in Cornwall

But I must tell you more, because while I fondly count them both as friends, the two mean more to me and to my work than just that friendship. Before Gods&Radicals Press was founded, before there was anything approximating an anti-capitalist pagan movement, and before I knew either of the two, I happened upon an essay which still makes me shudder when I read it.

That essay, by Peter Grey, was called “Rewilding Witchcraft.” Its words sounded a call not just to me but to dreaming witches everywhere, summoning us to return to a witchcraft of teeth, claw, and fur, a feral sorcery, a wild magic.

Confront death, not by pretending that you have cut a deal with the Elder Vampire Gods invented for you by some internet Dark Witch fantasist. Confront death, not by pretending that a beautiful Beltane ritual and a blue sky means everything will stay the same. Confront death, not by practicing the magic of ploughmen and wortcunners in your urban basement believing that it makes you more authentic than any given Wiccan. ... We are not simply losing it all, it is being stripped from us as surely as those accused of being witches were by their inquisitors in the torture cell. Our enemies are not our sisters and brothers in the craft, they are the named individuals and corporations and their governments who are tearing out our living flesh. Witchcraft has never been about turning the other cheek to this. The witch has been created by the land to act for it.

“Rewilding Witchcraft” was not just a call to an “authentic” witchcraft, but to an oppositional, rebellious, engaged, and savage witchcraft in the face of environmental and civilizational collapse. To say this essay was a summoning is to understate; rather, it screamed, chanted, and evoked into being much of what we think of as witchcraft now, awakening a lust we’d previously forgotten could be consummated.

From the space that essay opened into the asphalt choking the territory of our dreaming, this project found seed and root years before I’d met the two. Thirsting for more, I then read Peter’s Apocalyptic Witchcraft (a must for any who finds resonance in the work of Gods&Radicals Press), then began devouring the other essays collected on Scarlet Imprint’s site

The Brazen Vessel collects those works and previously unpublished essays. And while many of these essays are still available online, the true worth of this book (besides the obvious physical joy of running finger across artfully-printed and bound paper as you read) is that the writings of both Alkistis and Peter are presented together in way that provides the same depth perception which arises when you see with both eyes or hear with both ears.

Whereas Peter’s essays sometime betray that inescapably “masculine” problem of concrete aloofness (as with, for example, all of my own writing), Alkistis’s writing feels relentlessly embodied. To compare them beyond that runs the risk of suggesting a hierarchy, which would be as absolutely artificial as any other dualism. Instead, consider again what is seen because you have two eyes and not merely one, or how you can pinpoint the source of a noise because you have two ears rather than one.

Or better still (and a comparison I think they’d agree with), consider what happens as you walk. We moderns foolishly consider a leg to be “dominant” when we lead our step with it, forgetting that while it is in the air to propel us forward, we are completely held upright and stabilized by the other, which only takes its own step once the first takes on its former role.

Thus, the essays of both Alkistis and Peter act not like point/counterpoint, but left eye/right eye, or left leg/right leg, constantly propelling the reader together into deeper territories of perception. Neither can be pinned down to a particular focus and very often not even always to a particular writing voice (hardly a surprising thing from two writers who are also lovers).

Many (but hardly all) of Alkistis’s essays focus on the primal, ancestral, and embodied aspects of witchcraft through dance, the voice, and the erotic; many of Peter’s essays likewise delve into the power of erotic embodiment. Many of Peter’s essays explore the construction of witchcraft as a transgressive category born of the needs of (and yet also oppositional to) empire and the church; so, too, do the essays of Alkistis. Despite knowing them both personally, I often found myself referring to the footers to verify which of them I was currently reading.

So The Brazen Vessel is not merely a collection of essays by two writers, but rather a collaborative work born from an erotic coupling of two brilliant and fierce minds, their voices seamlessly weaving in and out of the other’s the way all the best conversations do. And what springs forth from this erotic collaboration is a book I suspect generations of rebels will recognize as a powerful ritual of initiation.

Alkistis Dimech and Peter Grey are not just writers, nor are they only witches: they are also revolutionaries. Not the black flag/black mask anarchist sort, not the party and union communist sort, nor even the primitivist anti-civilizational sort. In fact, any attempt to define their politics would have the whole thing backwards.

What we define as “leftism” now is only constellated according to Empire’s co-ordinates; never do we ask what leftism could be if it stopped letting itself be defined by what it opposes and instead by what it desires. The Brazen Vessel provides a kind of dream-map for those of us who’ve forgotten that we can even desire at all, let alone manifest those desires. It is a book for those of us trying to make sense of civilizational collapse, modern alienation, and environmental destruction, not by asking “how do we fix this?” but rather, “what did we sell of ourselves in exchange for this unwanted apocalpyse?”

This point is made particularly clear not just in Peter’s “Rewilding Witchcraft,” but also in his “Forging the Body of the Witch,” and by Alkistis in “Dynamics of the Occulted Body” and “The Witches’ Dance,” the latter two of which particularly invoke a mournful desire for the reclamation of our sublimated, abused, and forsaken bodies. As both repeat in a myriad of ways, the body is the site of witchcraft, the territory of our magic, and also the most hideous Enclosure enacted by Empire. A savage and powerful witchcraft is a witchcraft of the body, its potentials, its movements, its capacity to endure and transform pain and trespass perceived limitations (see Peter’s “The Amfortas Wound” and Alkistis’s “Outside the Temple,” both deeply intimate essays). And it is a witchcraft that does not merely seek to channel the deeply erotic urges of the human body, but recognizes that there is no body—and thus no witchcraft—without the erotic (see “Raw Power” and “An Erotic Eschatology of Babalon,” both co-written essays).

The theme of the witch-as-body is a crucial part of The Brazen Vessel; just as crucial are the essays one might initially call more “political.” But as with creating a duality between Alkistis and Peter’s distinct but interweaving voices, dividing their essays in this way isn’t quite correct. Fully inhabiting a body in an era of bio-political control and surveillance is an act of defiant political rebellion (see Peter’s “Beneath the Rose”), as is even using the full range of a human voice (see Alkistis’s “Carnal Voices”), and the need to do so at all speaks to the history of political control and subjugation of the body, especially bodies of women. If anything, my immediate urge to skip through the book for what I deemed “more political” betrays how much more I needed to read those other essays instead.

That said, three essays in particular comprise what I believe to be crucial contributions to a “occult political theory,” or perhaps a “political theory of witchcraft.” The first is Peter Grey’s “Fly The Light,” originally a speech given at the Psychoanalysis, Art, and the Occult Conference in London, 2016. In that essay, Peter discusses the Jungian shadow as it relates both to the witch’s interaction with the imaginal realm and subtle bodies, as well as to our current highly-digitized existences.

The shadow is one way that we can communicate with subtle intelligences in a dynamic exchange. I contend, however, that in the digital age the shadow has been excised, and deliberately so. The seeming aim of late capitalist culture is to produce what I call the body of surfaces, by which I mean the virtual body. Untethered from the relationship with light and shade that the body affords and that the heavens enact, the virtual body casts no shadow. In alchemical terms it partakes of no natural processes, it is entirely inert. Nor is such a body entitled to a shadow in the modern digital panopticon, where it is lit from every direction at all times.

Arguing from this obscured shadow and building upon this idea of the “body of surfaces,” he offers a guidepost from which occult knowledge can lead us to means of subverting the hegemonic dominance of political propaganda and media:

A magician knows that when you are being shown something—the only function of the body of surfaces—it is because something else is being concealed; a trick, a prestige, from praestringere, to blunt the removal of the world itself and its living systems. We are not only practioners of magic, we are victims of it, that is, until we have stitched the discomforting shadows back onto our world. At present, we live in quite the opposite, in an era of apokalapysis, of revealing; we live in a redacted media culture peopled by reflections.

And on this matter of apokalpsys, the clearest essay towards a political theory of the occult is Peter’s “Seeing Through Apocalypse.” Opening up with a discussion of the phenomenon of “normalcy bias” (the apparent bodily refusal to believe a crisis is really occurring despite overwhelming information that is is), and its likely evolutionary function to prevent our ancestors from being eaten by large prey (standing still when you spot a bear is in many cases safer than running), the essay then proposes the role of the magician’s training in changing this response:

The role of the magician is not initially to be the tiger, but first to see the tiger. To recognize patterns, to replicate patterns, and then to change them. An important concept here is the the martial one of being open on all eight sides. A figure to consider here is the spider, useful in both moving and sitting meditation. In Ninjuutsu this awareness is called the eyes and mind of god. It was the only way to survive in the seeming chaos of the ancient battlefield, and is the way to be in our pattern crazed world teeming with jewelled tigers. We must be sensitive to tremors in the web.

Following this observation, the essay argues that the effect (inadvertent and intended) of the intense mediation of late capitalist life, as well as the constant stress of the urban environment and the perpetual push for improvement via products, is to keep humans in constant states of stress. This eventually mutes, weakens, and negates our responses when crises actually occur. That is, when all of life is relentless, low-grade crisis, we cannot respond to the actual tigers in the grass (climate change, environmental destruction, extinctions, totalitarian surveillance, resource scarcity) when they appear.

But a third essay deserves particular attention, “Black Mass, Bright Angel.” As with many other essays in The Brazen Vessel, it was first presented as a speech, in this case at the Flambeau Noir/Black Flame conference in Portland, Oregon. Readers may be familiar with the recent incidents at another (canceled) conference bearing that name (Black Flame Montreal): several invited speakers were shown to have startling ties to Operation Werewolf (a proto-fascist group) and when prominent herbalist and writer Sarah Anne Lawless confronted the organizers about these ties, she was virulently attacked for bringing her concerns to light.

The occult, more so than heathenism and paganism, has a deep problem with infiltration. I suspect this problem stems from the same obscurantist habits in occult writing: it’s quite easy to hide your true intentions if no one (including yourself) can actually understand what you’ve just written. Peter and Alkistis have previously fought against fascist incursions (denouncing, for instance, the National Anarchism of Troy Southgate), so it should be no surprise that the speech presented in Portland makes deeply clear where he stands on such things.

I laughed when I first read the speech, knowing there would have possibly been some fascist sympathizers in the audience. “Black Mass, Bright Angel” is not just Luciferian but Lokean. Peter marshals a barrage of philosophers any leftist will recognize (Zizek, Bataille, Deleuze, Debord, Agamben, Baudrillard, Derrida, and Graeber, amongst others) to argue for the embrace of Bataille’s “sacré gauche,” a ritual, magical, and erotic rebellion against the hierarchical regimes of dominance, order, and purity. It is those regimes which made “unclean” and “untouchable” not just sexual fluids (particularly menses) in the monotheistic religions but also some humans into “slave” and others into “master” in our more recent history. Those regimes continue to set aside ever greater parts of humanity (the poor, the disabled, women, queers, the Global South, etc. etc.) as the discarded waste of civilization, and Peter proposes that the revolt of the fallen angels is a perfect map for a Dionysian, Luciferian revolution against these regimes.

The Brazen Vessel is a brilliant collection, but I must say it is also incomplete. As suggested in these discussions about a political theory of the occult, there are many essays which hint at much greater questions to be asked and answered. Particularly, in several essays (especially the final essay, “An Erotic Eschatology of Babalon”), the reader begins to sense that there’s much more work to be done tracing the dimensions and influences that certain occult figures have had on the current order of things. For instance, we are teased repeatedly regarding John Dee’s role in shaping the British Empire and consequently the American one, and multiple allusions to the magical dimension of our current order (“We are not only practioners of magic, we are victims of it...”) leave us begging for more collections exploring just these matters alone.

But perhaps that work is up to the rest of us. The work Alkistis Dimech and Peter Grey have done in their own writing and their publication of other profound—and readable—books has already laid the groundwork for serious examination of these questions. Without their work, my own work and the work of others here at Gods&Radicals would likely not exist.

For my part, The Brazen Vessel then arrives not as a mere collection of essays but another summoning to more engagement, as well as grimoire of rituals we can incant and embody to manifest the world we wish to see.

The Brazen Vessel is Available from Scarlet Imprint here.

Rhyd Wildermuth

Rhyd is a druid, theorist, autonomous Marxist, and a writer. He’s also the co-founder of Gods&Radicals Press and runs its publishing operations. He writes here, at Paganarch, and co-hosts the Empires Crumble podcast with Alley Valkryie. His most recent book, All That Is Sacred Is Profaned, is available here.