The Original Heresy: Homesickness, Civilization, and Transcendental Religion (part 2)

… continued from part 1.

“I am homesick. I’ve been homesick for years, maybe my whole life. The trouble is, I don’t know where home is or how to get there.”

The Wild Without and Within

Every so often, I have to get to the woods. I pack my backpack and head off to the mountains of West Virginia or the upper peninsula of Michigan or the red rocks of eastern Kentucky. If I don’t do this periodically, I start to get stir crazy. There’s something about being in a forest, alone and “away from the things of man”. It renews me and sustains me, in a way that nothing else does. Pine forests are especially potent places for me. In the forest, I feel immersed in the great presence that is the green and brown and blue world, suffused with the sound of the wind blowing through the trees and the smell of the forest filling my lungs, my whole body pulsing to the feeling of my heart beating in my chest. This is where I feel most alive.

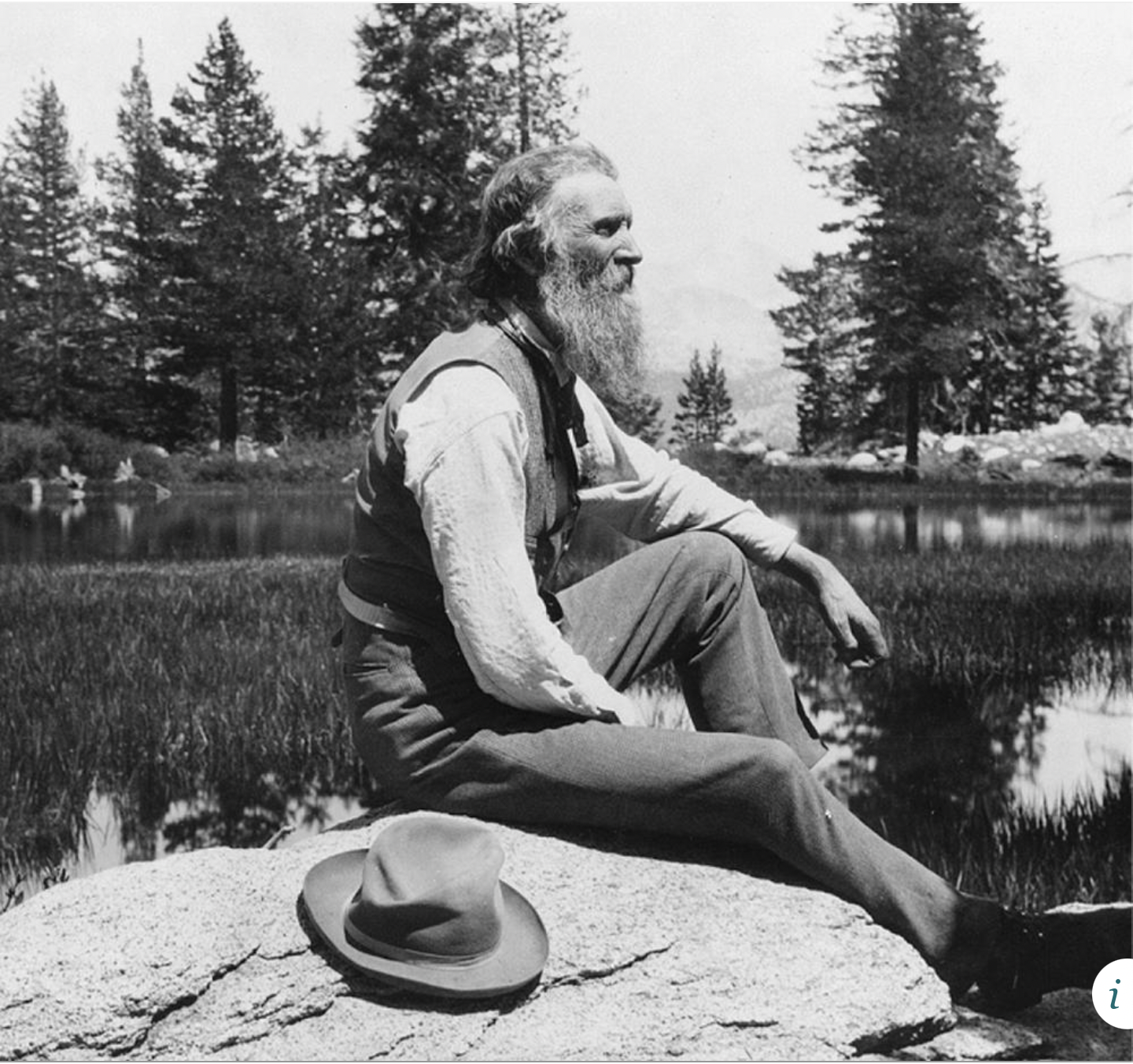

John Muir, circa 1902.

John Muir, who is credited as the father of the U.S. national park system, believed that all human beings need to spend time in wild places for both our physical and mental health. “Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play in and pray in, where Nature may heal and cheer and give strength to body and soul alike.” This wasn’t simple sentimentalism; Muir saw wilderness as an antidote to the deleterious effects of civilization: “In God’s wildness lies the hope of the world — the great fresh, unblighted, unredeemed wilderness. The galling harness of civilization drops off, and wounds heal ere we are aware.” Muir believed that wild places are our natural habitat and that cities make us physically and mentally ill.

“Thousands of tired, nerve-shaken, over-civilized people are beginning to find out that going to the mountains is going home; that wilderness is a necessity; and that mountain parks and reservations are useful not only as fountains of timber and irrigating rivers, but as fountains of life.”

— John Muir, Our National Parks (1901)

“Tell me what you will of the benefactions of city civilization, of the sweet security of streets—all as part of the natural upgrowth of man toward the high destiny we hear so much of. But I know that our bodies were made to thrive only in pure air, and the scenes in which pure air is found.”

— John Muir, in John of the Mountains: The Unpublished Journals of John Muir (1979)

Muir wrote that civilization had had a domesticating effect, not just on wild nature without, but on the wild nature within us. Wallace Stegner expressed a similar sentiment in his 1960 “Wilderness Letter”:

“We are a wild species, as Darwin pointed out. Nobody ever tamed or domesticated or scientifically bred us. But for at least three millennia we have been engaged in a cumulative and ambitious race to modify and gain control of our environment, and in the process we have come close to domesticating ourselves.”

— Wallace Stegner, “Wilderness Letter” (1960)

This is why we civilized people often feel what Muir described as “a vague longing and gnawing unrest”. “Civilization engenders a multitude of wants, and lawgivers are ever at their wits’ end devising,” wrote Muir, “The hall and the theatre and the church have been invented …” all to satisfy this longing. But they fail, because what we need is not more civilization, but the wild. “The truly lonely dwell in cities. The mountaineer is never lonely … He soon discovers that he is a part of all he sees, and that going to the mountains is going home.”

Why does the forest make me feel this way? Why do I feel more at “home” in the woods than in the place I actually live? Why do wild places resonate more deeply with me than the place that I have consciously constructed for myself? Why is it we can feel like strangers at home and at home in strange places? Why do we sometimes feel alone when we are with others and connected when we are alone?

I think the answer is that there is something wild in us, something that remains undomesticated, in spite of thousands of years of civilization. It’s in our DNA … or maybe our souls, whatever that might mean. Some inarticulate, felt connection to wind and water, sun and soil, and to other wild beings. And it’s that part of us that comes alive in wild places.

Our everyday world, the civilized world, is an instrumental world, where everything exists for us, as a tool or a resource. Similarly, we ourselves are tools and resources for others with power. When we go into the woods or the desert or the mountain or the seashore, though, we encounter a world that is there, not for us, but for itself. It is wild[9]. It is un-domesticated and un-civilized. And in those places, the part of us that is still wild, un-domesticated and un-civilized, wakes up.

“Civilization has always been a project of control, but you can’t win a war against the wild within yourself.”

— Paul Kingsnorth*, “Dark Ecology”

The Apollonian & Dionysian

The anti-feminist humanities scholar, Camile Paglia, is a fervent apologist for civilization. Drawing on Nietzsche, she theorizes that there are two forces which drive humanity: the “Apollonian”, which she relates to rationality, progress, and the masculine, and the “Dionysian”, which she relates to nature, sex, and the feminine. These two forces, which correlate approximately with the transcendental and immanentist impulses I described in part 1, exist in a creative tension.

But according to Paglia, all of Western civilization’s achievements are the result of one side of this equation, the Apollonian impulse, which she describes as the fight against the “long slow suck” of the fecund “swamp” that is the Dionysian “womb”[10]. Paglia is only half right. Civilization is the product of Apollonian excess, of a hyper-focus on growth, on progress, on individuation, on rationality. But the loss of the wisdom of the Dionysian counter-movement has been a calamity for humanity.

As Western civilization secularized, the transcendental impulse was not lost, only transformed. The function of the Christian God shifted to humanity, enlightened by science, empowered by technology, and self-assured in its belief in our own righteousness. Heaven was transformed into the heavens, the stars, outer space. The original heresy became the new gospel of perpetual progress. And salvation took the form of individual immortality via uploaded consciousness and collective immortality via colonizing other planets.

“Probably the central story of our culture—which I think has replaced a lot of the religious stories that used to be at the heart of our culture—is the story of progress: … human beings started as ignorant savages and are moving through a series of progressive steps, in which, at every point, they get cleverer … Eventually, that ends with us probably leaving the planet and colonizing the stars, or living forever, or downloading our brains onto silicon chips. It’s a kind of technological rapture that sees time in a linear fashion rather than in a cyclical fashion.”

— Paul Kingsnorth*, “The Myth of Progress” (interview).

Still, the earthly, Dionysian part of us survives, sometimes as little more than a shadow in our unconscious. We have yet to be able to escape our bodies or this earth entirely, after all. As Samuel Beckett wrote, “You’re on earth. There’s no cure for that.” So, occasionally, an immanentist impulse will manifest in countercultural movements, Dionysian antitheses to the Apollonian thesis of Western civilization, like the 19th century Romantics, various back-to-the-land and primitivist movements, and contemporary Paganism. But most of these movements were or are relatively small and/or ephemeral. (On the dark side, it would also manifest in fascism.)

Even after I left Christianity behind formally, the feeling of disconnection which I knew so well persisted. Though I had no name for it now, having rejected the religious terminology with which I had previously made sense of the feeling. But now there was another feeling too, just on the periphery of my consciousness, whispering …

there is still

somewhere deep within you

a beast shouting that the earth

is exactly what it wanted—— Mary Oliver, “Morning Poem”

When I left Christianity, I knew I needed something different. I needed a religion that would ground me in my body and in the earth, and connect me with the wider world. When I found Paganism, it seemed like the answer. Of course, as with any religion, Paganism can also be interpreted in different ways by different people.

The Gnostic Temptation

The god of dirt

came up to me many times …

now, he said, and now,

and never once mentioned forever,

which has nevertheless always been,

like a sharp iron hoof,

at the center of my mind.— Mary Oliver, “One or Two Things”

In spite of being a nominally “earth-centered” religion, there is a significant transcendental impulse in contemporary Paganism. Pagan studies scholar and animist, Graham Harvey, calls this the “Gnostic temptation.”

To begin with, there’s a lot of esotericism or occultism mixed in with contemporary Paganism. “Esotericism” and “occultism” refer to a nexus of related quasi-religious movements which share the notion that secret or hidden knowledge is available only to a small, elect group and only through intense study. Much of contemporary Paganism has inherited ritual forms and theology from British Traditional Wicca, which did not itself begin as a nature religion, but as an esoteric mystery religion[11].

In the esoteric tradition, the value of nature lies in the hidden truths it holds for the initiated, rather than having its own intrinsic value apart from its usefulness to humans[12]. As Esme Partridge explains in her essay, “Witchcraft Isn’t Subversive”, “Western occultism came hand-in-hand with the founding principle of the modern age: Man’s domination over nature. […] Western esotericism does not subvert the impulse behind capitalism, but complements it.” The instrumental understanding of magic, in particular, perpetuates a view of nature as an object existing only to fulfill human desires[13].

Depending on the form it takes, polytheism may also be a contributor to the transcendental impulse. Unless they have a visible and physical manifestation grounding them in the natural world, the belief in supernatural beings, including anthropomorphic gods, fairies, and so on, can also be a manifestation of the transcendental impulse[14].

In addition, there is a little appreciated civilizational bias to most reconstructions of ancient polytheisms. We are reliant on the writings of ancient peoples to know what they believed about their gods. Even material remains, like painted pottery and statues have to be interpreted through written or inscribed texts. (To illustrate this, just consider the debates around the meaning and purpose of the Palaeolithic “Venus” statues, interpretations of which range from sacred objects to masturbatory aids.)

Most non-civilized people had oral cultures, whereas writing developed out of civilization because the elites needed a technology to keep track of their surplus property and to tax commoners. So while we can reconstruct the religions of the urban polytheists, it’s practically impossible to reconstruct the religions of rural (i.e., “pagan”) peoples—except through the jaded lens of civilized authors writing (usually dismissively or denigratively) about their rural contemporaries or predecessors. What’s more, within civilized societies, only a small percentage of people were even literate. (It was under 5% in ancient Rome, and less in other civilizations.) As a result, contemporary reconstructions of ancient polytheisms are necessarily reflections of the structures of power and the values of elites within civilization[15]—and thus are biased toward the transcendent.

Egyptian Stele of Qadesh depicting Resheph, Qudshu, and Min.

By way of example, consider the Qadesh stele which I mentioned in part 1. This image is a primary source for some polytheist reconstructionists. For one such reconstructionist, “it is a holy image representing the careful balance of powerful forces held in check, one to the other, both ever-present, ever-necessary, in this world simultaneously.” This is similar to my own eclectic interpretation in part 1. But neither interpretation acknowledges that the stele is a political document, one which was created in a specific political context, probably a memorialization of the peace following the Battle of Qadesh in Canaan between the Egyptian and Hittite empires in 1274 BCE. The gods depicted in the stele are literal stand-ins for the Egyptian, Hittite, and Canaanite civilizations.

Whatever meaning these gods had to the common people, the stele appropriates them for the purposes of empire. And this is not unusual. The vast majority of texts and iconography relied upon by polytheistic reconstructionists are artifacts of civilization, and thus of religious and political elites, not common people. We are left to imagine how the gods of the commoners of Qadesh differed from the depictions of their elite contemporaries. But it is probably safe to speculate that they would have been more grounded in local landforms and ecosystems, their personalities would have been more reflective of the common people than of priestly and political elites, and their functions would have been more reflective of the life of the family and tribe than of the hierarchy of the state.

The “Mystery”

The transcendental impulse in general, and the esoteric influences within contemporary Paganism specifically, are symptomatic of a human tendency to look for our answers everywhere except where and when we already are. We look to the past or to the future, to heaven or outer space. But the greatest secret of paganism is an open one. It’s a secret only to the extent that we’re not paying attention.

No esoteric knowledge has to be passed on orally through the centuries for paganism to survive, because we carry it in our flesh and blood. It is a function of our co-evolution as a part of the living world. We can be pagan again today because we live under the same sun on the same earth and feel the same wind blowing in our hair and the same rain falling on our skin. There are many differences, of course, between humans then and now. But at our most fundamental, we are still the same human beings we were ten thousand years ago.

The great “mystery” of many religious traditions is, in fact, that there is no mystery. As Jesus reputedly said, “The kingdom of God is in your midst.”[FN 16] It’s so simple and yet profound, so obvious it’s easy to miss. Our religions—including contemporary Paganism—keep complicating it with great systems of thought and interposing intermediaries—both human and ideological—between us and it. But the mystics of the world’s religions, mystics like the Hasidic philosopher Martin Buber, call us back to the direct, unmediated experience:

“There is something that can only be found in one place. It is a great treasure, which may be called the fulfillment of existence. The place where this treasure can be found is the place on which one stands. …

“We nevertheless feel the deficiency at every moment, and in some measure strive to find—somewhere—what we are seeking. Somewhere, in some province of the world or of the mind, except where we stand, where we have been set—but it is there and nowhere else that the treasure can be found. …

“If we had power over the ends of the earth, it would not give us that fulfillment of existence which a quiet devoted relationship to nearby life can give us. If we knew the secrets of the upper worlds, they would not allow us so much actual participation in true existence as we can achieve by performing, with holy intent, a task belonging to our daily duties. Our treasure is hidden beneath the hearth of our own home.“

— Martin Buber, The Way of Man (1948).

Being “pagan”

It’s become de rigeur for Pagan writers to observe that the word “pagan” comes from the Latin paganus, which referred to the people who lived in the countryside, contrasted with the people who lived in cities. The word later took on other connotations, but this original meaning tells us something important. To be pagan—then and now—means in some sense to stand outside or against the alienating forces of civilization. It means to practice a “devoted relationship to nearby life”—to the land on which we are standing, to the human and other-than-human people we share that land with, and to our physical bodies in contact with those other bodies.

This sense of the word “pagan” overlaps only partially with the contemporary Pagan community. It’s what theologian Michael York describes as a spontaneous human response to being in the wild world. “Stripped of its theological overlay or baggage,” he says, it is the “root” of religion[17]. This atavistic impulse tends to surge up spontaneously and unpredictably, sometimes in unlikely places, among peoples of diverse beliefs (including Christians). It sometimes takes the form of a revival of ancient pagan ways of being in the world, though not always recognized as such. It’s not a set of beliefs (paganism isn’t really an -ism at all) or even a set of religious practices, but a relationship—an organic relationship with the living world.

I’m talking about those experiences which invite us to come down to earth, to come back to our one and only home. I’m talking about rituals which arise without effort, spontaneously, as a result of contact with the Holy Body of the earth. I’m talking about instinctual practices which restore our sense of being alive in a living world.

Paganism is about being here and now.

Paganism is the moment when you are the most alive and most aware of the world around you.

Paganism is the moment that sweeps you away into spontaneous ceremony and celebration of the life within and all around you.

Paganism is the place where you feel the most at home, the place where you connect to the natural living world in deep and intimate ways.— adapted from Glen Gordon, “What is Postpaganry” [archived].

That organic relationship is our birthright as human beings. But five thousand years of civilization have done their work, breaking the connection between us and nature, reducing the more-than-human world to object, resource, and commodity. To be pagan today is to try to reclaim what Emerson called our “original relation” with the world.

To be pagan is nothing more and nothing less than to be fully human, fully human in a more-than-human world. The alienating forces of civilization—including Christianity, yes, but also capitalism, industrialism, the Enlightenment, and patriarchy—have divided us from ourselves, from each other, and from the more-than-human world. The work of being pagan today, then, is to reclaim our humanity. As Steven Posch writes:

… “pagan” isn’t something that you convert to.

Pagan is what you already are.

Paganism is inherent in human experience. Everyone is born pagan.

Anything else, you have to be made into.

“Becoming” pagan, then, is a process of recovering what’s already yours, yours by right.

— Steven Posch, “Pagans Don’t Proselytize; We Don’t Need To”.

As I left the Christian religion of my upbringing behind, I gradually realized that my only “sin” was not loving life—this life—enough. As Albert Camus said,

“If there is a sin against life, it consists perhaps not so much in despairing of life as in hoping for another life and in eluding the implacable grandeur of this life.”

— Albert Camus, “Sumer in Algiers”.

I eventually came to see that what I needed was not transcendence, not escape from the material world, but to experience that world more fully, more deeply and intensely. As I developed my personal pagan practice, I included prayers at my private altar. At night, I would recite the same prayer, which concluded with these words:

“Teach me to love this world.”

Over time, I have felt this simple prayer work its magic in me, helping me unlearn the original heresy, bringing me down to earth, cultivating a passion for this life. Slowly but surely, I began to look for what I was seeking, not in heaven or in my imagination, but in the very physicality of the world that we are immersed in: in the wild wind before the spring storms, in the feel of the soil in my garden under my fingers, in the warmth of the sun on my face, in the water flowing over my body from my shower head, in the flow of breath in and out of my chest as I take my first conscious breaths in the morning, in the beating of my heart and the burn in my muscles as I hike through up a mountain, in the taste of a ripe pear melting on my tongue in summer, in the heat and sweat of my lover in congress, in the hand of a friend grasping mine, and in the transience of this very moment.

It’s taken years, but slowly I have come to feel a shift in myself. My internal compass has moved from the transcendent to the immanent, from the heavens back to the earth. I still carry a certain ambivalence about the messiness of matter and the embarrassment of embodiment. But (to paraphrase Robert Frost) I can now say that my quarrel with the world is that of a lover.

Notes

9. Wildness is not an absolute condition, but a matter of degree. We are experiencing the rapid disappearance of places we call wild or “wilderness”. There is no place where the impact of civilization is unfelt, even in our national parks. But at the same time, we are also realizing that, in a very real sense, there is no place that isn’t wild to some extent. There is no place where human power is absolute, even your own backyard. Climate change is just one reminder that our control over nature is always incomplete at best.

10. Paglia would have benefited from a closer reading of Nietzsche, who saw a balance between the Apollonian and the Dionysian as necessary. Or she could have read Carl Jung, who understood healthy psychological life as existing in the tension between the Apollonian drive for (masculine) individuation and the Dionysian drive to return to the (feminine) source of our power and inspiration. Balance is key. As Jungian analyst, Edward Whitmont, explains in Return of the Goddess (1982), “In excess this [Dionysian] dynamic can lead to madness, nihilism, and annihilation; yet its total absence means petrification, rigidity, and grim, joyless boredom.”

11. See Wouter Hanegraaff, New Age Religion and Western Culture: Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought (1997); Joanne Pearson, “Demarcating the Field: Paganism, Wicca and Witchcraft”, DISKUS Volume 6 (2000).

12. See Chas Clifton’s distinction between a symbolic “Cosmic” nature and an embodied “Gaian” nature, in Her Hidden Children: The Rise of Wicca and Paganism in America (2006).

13. See Trudy Frisk, “Paganism, Magic, and the Control of Nature”, Trumpeter (1997). There are Pagans who already have developed and continue to develop alternative, non-instrumental conceptions of magic: from Starhawk’s classic formulation of magic as the art of transforming consciousness to Julie Schutten and Richard Rogers who describe magic as a way of communing with other-than-human beings. “Magic as an Alternative Symbolic: Enacting Transhuman Dialogue”, Environmental Communication 3:3 (2011).

14. There are Pagans who have developed alternative, naturalistic understandings of gods, such as Steven Posch, who invites us to make the “radical leap out of our own internal dialogue and into actual relationship with real, non-human others”: sun, moon, earth, storm, sea, wind, fire, plants, and animals. Steven Posch, “Lost Gods of the Witches”, Pentacle (2009). See also, Alison Leigh Lilly’s “natural polytheism”, described in “Anatomy of a God” and “Naming the Water: Human and Deity Identity from an Earth-Centered Perspective” [archived].

15. In Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States (2017), James Scott explains how states would have come to dominate the archaeological and historical record because (1) most archaeology and history is state-sponsored and “often amounts to a narcissistic exercise in self-portraiture.” Compounding this institutional bias is the “monumental bias”: “if you built, monumentally, in stone and left your debris conveniently in a single place, you were likely to be ‘discovered’ and to dominate the pages of ancient history. If, on the other hand, you built with wood, bamboo, or reeds, you were much less likely to appear in the archaeological record. And if you were hunter-gatherers or nomads, however numerous, spreading your biodegradable trash thinly across the landscape, you were likely to vanish entirely from the archaeological record. … Once written documents—say, hieroglyphics or cuneiform—appear in the historical record, the bias becomes even more pronounced. These are invariably state-centric texts: taxes, work units, tribute lists, royal genealogies, founding myths, laws.” For a discussion of the contrast between folk/popular religion and elite/official religion in Biblical times and places, see William Dever’s Did God Have a Wife: Archaeology and Folk Religion in Ancient Israel (2005).

16. Recall that, in Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamozov, the Grand Inquisitor explains that the church had no need for the kingdom of the actual risen Christ, because they had embraced “miracle, mystery, and authority.”

17. In his book, Pagan Theology (2003), Michael York distinguishes what he calls “paganism” from “transcendentalism”: “Cultic behavior that is directed inside nature is pagan. But religious or theological behavior that directs itself outside of nature is transcendentalism of one form or another. Implicit in it—and distinguishing it from pagan behavior—is a devaluation of the natural.”

*Over a period of a few years, Paul Kingsnorth’s political orientation has shifted from Green anarchism to proto-fascism. While it is impossible to draw a bright line marking when this occurred, I cannot unequivocally endorse Kingsnorth’s writing after the spring of 2020. COVID and his conversion to Orthodox Christianity appear to have accelerated his slide to the right. See here for more on this.

JOHN HALSTEAD

John Halstead is the author of Another End of the World is Possible, in which he explores what it would really mean for our relationship with the natural world if we were to admit that we are doomed. John is a native of the southern Laurentian bioregion and lives in Northwest Indiana, near Chicago. He is a co-founder of 350 Indiana-Calumet, which worked to organize resistance to the fossil fuel industry in the Region. John was the principal facilitator of “A Pagan Community Statement on the Environment.” He strives to live up to the challenge posed by the Statement through his writing and activism. John has written for numerous online platforms, including Patheos, Huffington Post, and Gods & Radicals. He is Editor-at-Large of NaturalisticPaganism.com. John also edited the anthology, Godless Paganism: Voices of Non-Theistic Pagans and authored Neo-Paganism: Historical Inspiration & Contemporary Creativity. He is also a Shaper of the Earthseed community, more about which can be found at GodisChange.org.