In the Shadows of Election Power

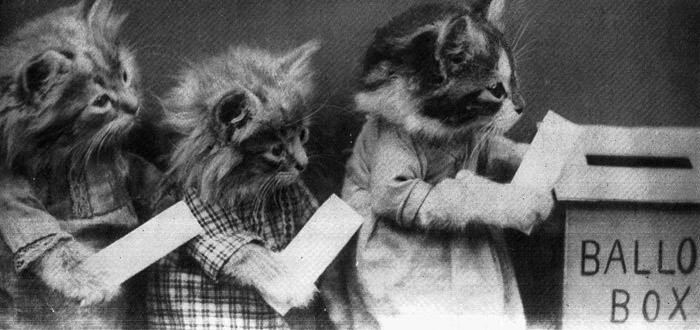

“There are forces, powers beyond humans in the more-than-human world, for whom it is always election season. Forest fires in the western United States are casting their votes. A virus that inhabits and moves between our bodies is casting its vote. And the systemic impacts of climate change are casting their votes in myriad ways: through extinction, desertification, and dead ocean zones. Who or what are they voting for?”

From Nathan Kleban

In the U.S.,I cast my vote out of fatigue and frustration in fear of the menace of a worse candidate. I vote in a non-swing state; it seems like my vote doesn’t matter. But in my seeming powerlessness, I seek the hidden places where power, the capacity to affect change, lies—beyond voting, beyond humans. I’ve caught a glimpse of what moves outside of human systems and activisms.

Elections are important (I recall the oft-repeated Chomsky line, that voting is something to think about for a moment, do, and then move on from), but voting is only one way that power is exercised. I am not just talking about how life presents us with manifold opportunities to choose other than voting. I am also not just talking about powers besides electoral forces converging and shaping the outcome of a U.S. election. I’m talking about the swirl of powers at large, about how little power seemingly powerful humans actually have.

Whoever holds this or that elected position is meaningful and worth discussing, but when our awareness centers on the spectacle of the circus of elections, we give undue importance to election day choices that cloud out and distract from other sources of power (i.e. while it feels like Trump being in office versus Biden makes an enormous difference, Joe “Nothing will fundamentally change” Biden promises only subtle changes in an ongoing capitalist and neoliberal order.). Elections are spotlights that obscure, hide, and interact with other powers in different ways.

Other than elections, what sources of power am I talking about? First, since we’re talking about politics, let’s “follow the money” and examine how money informs and changes circumstances and what kind of power it has. We all know that capital, money, has power. Capital tends to increase its influence via the “profit motive”—people desire profit, more money, and they act accordingly. Capitalists are fairly clear about this, viewing money as the primary motivator.

Domestically, we see some wealthy people influencing elections so they’ll gain more money (e.g. influencing politics for tax cuts). Internationally, the wealthy use “trade” agreements to move their capital into other countries and commodify (put a price on) the sources of life: animals, plants, land (all “resources”), and people (“human resources”). When a place opens to foreign capital, when land can be bought and people can be hired using money, when the governing body’s coffers fill with the fees gleaned from these transactions, it becomes clear whose interests this government represents. With capital’s tendrils touching, grasping, as much as it can, it’s influence only increases. Money gains market power in the power “market.”

Given the seemingly all encompassing aspect of capital in our lives, when the power of capital is concentrated into the hands of a few, it reduces the ability of others (e.g. people, land) who have less capital to make choices that impact their own lives. When capital surges like a deluge across borders, the power local people have over their own lives is diminished. What they think doesn’t matter so much anymore when weighed against the power of money.

When I volunteered with the Peace Corps in Mali, I was given a monthly stipend of around $100, which went a long way in the local economy. While I could access (buy) an immense amount of food, some people around me were malnourished and starving (this is of course no different than where I am in the United States at present, but more stark). The time before the year’s first harvests were called “the starving season” because hunger was particularly a struggle. But during the starving season, there was food available and I could easily access it because I had money. Those who went hungry were not being served well by their governing institutions (the nation-state of Mali is itself a result of colonization and ongoing neo-colonial efforts). I could say that society decreed, or that capitalism dictated, but whatever the framing: I had a greater right to live in Mali than people who had lived their whole lives in Mali all because I had more money than them. Is it beyond the limits of our imagination to find a way for people not to die or go hungry due to lack of money?

Elections are a form of communal decision-making that theoretically should be about meeting the needs of those decision-makers— what do you think capital’s relationship with this is? Capital wants to expand its grasp, to eliminate obstacles in its way.

If capital is money, then capitalism is money-ism, in contrast with democracy which means: “the power of rule of the whole citizenry.” Capitalism is the “power of the rule of money.” Its motive is to expand itself, its underlying basis is its own importance, and its invasion across borders aims to increase its own power and capacity to change and influence others. Capitalism and the values that generally underlie elections compete directly against one another. The voter versus the shareholder. The common good versus private wealth. Billions of U.S. dollars are invested in its elections by those expecting a return. Fair elections undermine capitalism; capitalism undermines those without capital.

Certainly there are reasons we find money useful and beneficial. Money can be used to acquire basic necessities. Money has the power to bring people together, to support group efforts (like the writing, publishing, and distribution of essays like this). It coordinates relationships around which most people orient their lives and activities, and supports billions of humans in meeting their various needs.

Can a compromise be made so we can have the “best” of both worlds, a little bit of fair elections and local decision-making alongside capitalism? There are no examples of capitalist countries where concentrated power has not undermined large parts of the country, that haven’t destroyed or aren’t actively destroying their landbase. We already are trying to have the best of both worlds via neoliberalism. Instead of a democracy, we have an oligarchy of the wealthy. Instead of free and fair elections, we have open and brazen voter suppression along with stolen elections (see 2000 elections).

Though money extends its grasp to touch so much in our lives, it can only touch the surface. The more-than-human world (beings in community with humans: the animals, plants, rocks, rivers, microbes) is touched on this surface level as objects and things to be used and traded. On its own, money-as-tool being so human-centered is not an all encompassing decision-making process because it derives its decisions from a much too limited source—a democracy of some beings: those with capital. Value (what is important) and money aren’t the same thing. Rather than monetary value as a rough approximation of the “true” value of something, money values things in rough approximation to how those with money value those things (or rather those with money believe they confer value). Money only touches the surface of life and its values miss the more-than-human world. In seeing money’s limits we find other powers.

But what is power? I wrote above about political power, electoral power, the power of capital, and people power—and there’s so much more. Power has to do with the capacity to affect change, to shape the directions in which change flows. Power can also work to dam up or divert such rivers.

Power can show up as a physical blow to the head or with more complexity as a movie which shows us another way to see the world. In elections, one might use the power of capital to buy advertising with the purpose of gaining more political power. In advertisements, the words, the sounds, and the imagery take on a life of their own and have power to influence and change, such as Obama’s “Hope” poster and Trump’s MAGA hats. As the power of capital is set free in advertising, it gains its own potential. Words inspire action beyond voting. Images can induce fear or trust.

The information streams which feed us these perceptions, induce these emotions, move us to act and are acted upon in turn. We subscribe as Patreons, call it “fake news,” and share them with others. The unleashed streams gather into rivers, flow into creeks, disappear underground, then into the ocean. All along, water evaporates into clouds, moves in other ways, and falls to the earth once more. When I write of power this is what I mean—power flows away from its source.

An example of a stream that takes on its own force is “cancel culture.” Though I don’t have personal experiences with this, the narrative I hear is the unruly mob grabs their pitchforks and follows allegations of possibly dubious credibility, destroying anyone in their path. Or is it those previously without a voice making themselves heard? There are other forms of power involved, beyond that of the trending hashtags and the audience that is informed by attending to them. Cancel culture is a container for many different streams: differing conceptions of justice, histories of punishment: exile, red-baiting, witch burning, boycotts, and judicial trials. Cancel culture arises as but one stream fed by and feeding others.

If only cancel culture had the power to cancel capitalism, or at least provide different candidates! With Biden assuming power (or substitute whatever “lesser of two evils” you face here), the call will then be to continue supporting him at the expense of my deeply held values and the conversations about making change through activisms will likely continue to be restrained. In a Biden presidency, it’s hard to imagine anything other than our collective path’s trajectory increasingly worsening, with continued struggle over the horizon. What humans are doing isn’t working; we are far from where we want to be. I feel lost.

While I have a sense that humans have had a central role in this struggle, I’m not so sure we’ll have so central a role in healing, whatever that may look like, because the way humans center our own efforts, our own agency, our own agendas, is part of the problem. In my lostness, I am searching for another way, another path, another kind of election to participate in.

There are forces, powers beyond humans in the more-than-human world, for whom it is always election season. Forest fires in the western United States are casting their votes. A virus that inhabits and moves between our bodies is casting its vote. And the systemic impacts of climate change are casting their votes in myriad ways: through extinction, desertification, and dead ocean zones. Who or what are they voting for?

Power indeed lies elsewhere, outside of human institutions and money and activisms. When we de-center the human, when we see we are not the only actors on the stage, we finally see that we and our limited powers are not at the center of the living world. Rising sea levels and viruses make obvious the greater power dynamics at play.

The delusional allure of somehow aligning myself alongside the powers of the more-than-human world to achieve my goals is strong, as if I’m the religious zealot who thinks they know God and acts through said God. There is much that we don’t understand about the more-than-human world’s powers. We can so easily imagine them in human terms, but anthropomorphizing only takes us so far. What are the dynamics as they come to bear on human power structures: governments and elections, money, cancel culture? We are only beginning to grasp what kind of impact seemingly small temperature increases can make. We are finding ourselves fragile in new ways. What we once held up as strong is brittle; what once was inconsequential bears consequences. More lurks in the shadows, like the virus we named Covid-19, which only recently stepped out from the shadows into our lives. The importance of elections pale in comparison to the greater context. I don’t write this to denigrate elections and activisms and other human forms of power-making and changing; they are all important and can be life changing and life affirming. I participate in many of them myself. I’m just trying to see them in a different light.

In my search for paths beyond the election, I fear being deluded, of missing what’s real and what’s fantasy. I picture myself as some magician, gleaning the depths of matter and, once I understand, I utter the spell, the magic words, write the magic essay, the magic manifesto, conduct the magic activism. And—mimicking the depth and complexity of existence in a Rube Goldberg machine-like manner—the words cascade into a better world, a healthier existence for everyone. Or the fantasy is this: I look at all of the numbers and crunch them, absolutely crunch all of them, and after getting to the root of everything I pull the optimized lever at just the right time to make things right. I become the butterfly flapping its wings, only instead of a hurricane on the other side of the globe, war ends. Or capitalism ends. Or something Good comes. I’m not even sure what this kind of world might look like, only that my values and senses guide me.

That fantasy of complete understanding and of myself as an individual holding the keys to change speaks falsely to me. I believe I have a sense of what is real and what is fantasy. But where does this sense of what is real and what is fantasy fall apart? These concepts are constructions built over time that do not map perfectly onto experience. While wisdom from others about what “works” and what “doesn’t work” as far as effecting change goes is important, what might we be missing? What have we been missing that humanity is on the course that it is now on?

What I do know is that we are in this together, that we are not alone. I’m now seeing the “we” who are in this together has always been more expansive than I imagined. The “we” includes those with senses of agency and whose experiences I can only imagine and guess at. What I’m interested in is how to reckon this complexity of our co-existence, that we’re enmeshed in this all together, and we have choices to make and power to exercise as a democracy of all beings—what would participating in these “elections” look like?

NATHAN KLEBAN

Nathan wanders between various intentional communities such as Catholic Worker service communities and Zen Buddhist monasteries. His favorite thing to do is going into prisons to help facilitate intensive, experiential workshops on conflict transformation with the Alternatives to Violence Project.